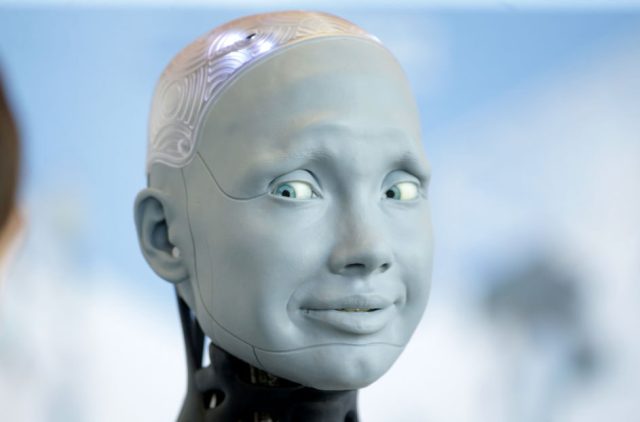

GENEVA, SWITZERLAND - JULY 06: Human-shaped robot Ameca of American manufacturer Engineered Arts interacts with visitors on July 06, 2023 in Geneva, Switzerland. Some 3,000 global experts from big tech, education, and international organizations will gather at a two-day summit in Geneva organized by the United Nations to discuss artificial intelligence in its potential for empowering humanity. (Photo by Johannes Simon/Getty Images)

In parts of Thailand, thanks to a confluence of modern technology and traditional beliefs, a peculiar transport service has emerged. The anthropologist Scott Stonington calls them “spirit ambulances”. Some Thai Buddhists feel morally obliged to preserve the life of an ailing mother or father by any means possible — even if there is no realistic hope of recovery, and even if it goes against the parent’s own wishes. Yet these same Buddhists believe that death should occur in the home, in the presence of family. So the dying parent is kept at the hospital until the last moment, receiving the best treatment medicine can provide, before being whisked home in a specially designed vehicle, the spirit ambulance.

In his new book Animals, Robots, Gods, Michigan anthropology professor Webb Keane uses such case studies to tease apart the intuitions of his Western readers. Medicine is only one area where the scientific worldview can blend seamlessly with local customs and perspectives. A Buddhist temple in Japan provides funeral rites for broken robotic dogs. In Taiwan, “one of the most prosperous, highly educated and technologically sophisticated societies in the world”, urban professionals maintain relationships with puppets and religious icons as well as video game avatars. Modern practices and technologies are adopted by cultures with widely differing views of justice, the self and the cosmos. This raises important questions as algorithms and autonomous robots gain a more active, pervasive role in our lives. Whose view of the world will be encoded in these systems, and whose moral principles?

Silicon Valley would have us believe the problem can be outsourced to experts: to professional ethicists, scientific advisors, lawyers and activists. But as Keane emphasises, these authorities tend to come from “a small subset of the tribe WEIRD”, that is, Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic. That they arrogantly claim to speak on behalf of a universal humanity does not make their assumptions any less partial and idiosyncratic. “There is no good reason,” Keane writes, “to take the WEIRD to be an accurate guide to human realities past, present or future.”

To see the force of Keane’s point, just consider Ray Kurzweil, a prominent thinker on AI and principal researcher at one of the world’s most powerful companies, Google. Kurzweil also has a book out, The Singularity Is Nearer, in which he resumes his decades-long project of encouraging us to merge with super-intelligent computing systems. Kurzweil does not think in terms of cultures, traditions or ways of life, only in terms of generic “humans”. What we all want, he asserts, is “greater control over who we can become,” whether by taking drugs to manipulate our brain chemistry or undergoing gender reassignment surgery. So integration with computers must be desirable, for “once our brains are backed up on a more advanced digital substrate, our self-modification powers can be fully realised”. Humans will then live indefinitely, and become “truly responsible for who we are”. This vision is both grandiose and astonishingly narrow-minded. Trapped in his utopian variant of secular materialism, it seems Kurzweil cannot fathom that a good life might be a finite one, that other principles might claim sovereignty over individual desire, or that acceptance of our limitations and fallibility might be integral to happiness.

Kurzweil also endorses the Asilomar AI Principles (drafted at a conference in California, of course), which state that intelligent machines should be “compatible with ideals of human dignity, rights, freedoms, and cultural diversity”. That sounds lovely, but try applying these principles to the Thai Buddhists we started with. Whose dignity and freedom should take precedence — the suffering parent who does not want further treatment, or the sons and daughters who feel compelled to provide it regardless? Should public health systems pay for “painful and expensive trips to the hospital and back”, even if they are “in biomedical terms, pointless”? How should we weigh karma as a factor, given its consequences for the Buddhist cycle of rebirths?

In Animals, Robots, Gods, Keane explores moral life beyond the abstract categories favoured by the WEIRD. If they are to be something more than thought experiments, he points out, moral systems must respond to the conditions that exist in a particular time and place; they must provide “possible ways to live”. In other words, “you simply cannot live out the values of a Carmelite nun without a monastic system, or a Mongolian warrior without a cavalry.” This may sound like the dangerous relativism of an anthropologist. Yet it simply illustrates that, as the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre argued, the search for moral truth is necessarily an on-going quest: a constant effort to develop our principles in relation to new circumstances. Of course, the principles and circumstances we start with are never ours to choose.

That said, there are commonalities across a range of moral cultures. These include fetishism, where, with varying degrees of seriousness, cultures assign quasi-human (or super-human) capacities to non-human things. This tendency allows for a variety of moral relationships beyond the immediate human sphere, including with animals, deceased or comatose relations, inanimate artefacts and invisible deities. And together with our locally rooted moral instincts, they shape our relationship with technology as well. “When people design, use and respond to new devices,” Keane writes, “they are drawing on existing habits, intuitions and even historical memories.” Such devices always arrive in cultures with their own ways of personifying the impersonal. In Japan, Keane suggests, the legacy of Shintoism makes people more willing to treat robots as living creatures, but also less worried about their moral agency; they assume that robots, like people, will be constrained by social roles and structures.

Western societies have their own forms of fetishism, which Keane examines in relation to Large Language Models such as GPT-4. Since these algorithms are just stitching together words and phrases according to probability, they have no sense of their statements’ meaning. In fact, they have no sense of anything. It is we, their users, who “must play an active role in accepting that it is meaningful”. And we do more than that. Echoing arcane religious practices such as divination and speaking in tongues, we take the very inscrutability of the algorithm as evidence of “special powers and insight”.

Again, it is difficult not to be reminded of Kurzweil’s messianic view of artificial intelligence. Though his latest book avoids his earlier speculations about a great eschatological explosion of computing power, which will one day transform all the matter in the universe “into exquisitely sublime forms of intelligence”, he does encourage us to embrace AI as a fetish. An algorithm may “think” by entirely different mechanisms to us, Kurzweil argues, but if it can “eloquently proclaim its own consciousness”, we should accept that it does indeed possesses “worthwhile sentience”. It is a good reminder that the WEIRD and the weird are rarely as distant from each other as they seem.

What Animals, Robots, Gods does not consider is the political context that has produced figures such as Kurzweil. The rise of advanced computing technologies in Silicon Valley largely coincided with an era of US hegemony after the Cold War. In that period, “globalisation” meant the spread of Western products and ideas, within a framework of American-dominated international institutions. At the same time, centres of business and research attracted talent from around the world, creating an illusion of diversity. All this allowed Western elites to persuade themselves that cultural differences could be managed through overarching, reductive moral rules like the “human values” listed in the Asilomar AI Principles.

Keane warns that, even if different peoples can adapt technologies to their own ways of life, many of them will still resent the prospect of powerful algorithms that are programmed according to Western assumptions. You cannot make the whole world WEIRD, he argues, “and if you try, you’re going to encounter a lot of anti-colonial resistance”.

But that horse bolted some time ago. Many societies in the far East already have distinct technological cultures. The Chinese Communist Party has long excluded US internet companies from the country, and closely regulates the moral dimension of digital media, down to the appearance of skeletons and vampires in video games. It is now testing AI algorithms to ensure they “embody core socialist values” — and avoid repeating politically sensitive information. The Russian state seeks a similar authority. In India, Hindu nationalists have infused the meaning and purpose of modern technology with their own religious and political mythologies. The achievements attributed to ancient Hindu science include stem cell research, spacecraft and the internet.

These centrifugal dynamics will surely continue. As the American world order fragments, so will our technological futures divide and multiply. Even if Silicon Valley continues to provide the most advanced tools, other regions of the world are knowledgeable enough to use them for their own purposes. If the West doesn’t like this, then China will be happy to export machine learning systems and intelligent hardware, as it already exports cloud computing and surveillance systems. Keane asks us to imagine Confucian robots, or artificial intelligence as conceived by cultures that locate the self across multiple bodies and lifetimes. These, too, may soon be more than thought experiments.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe