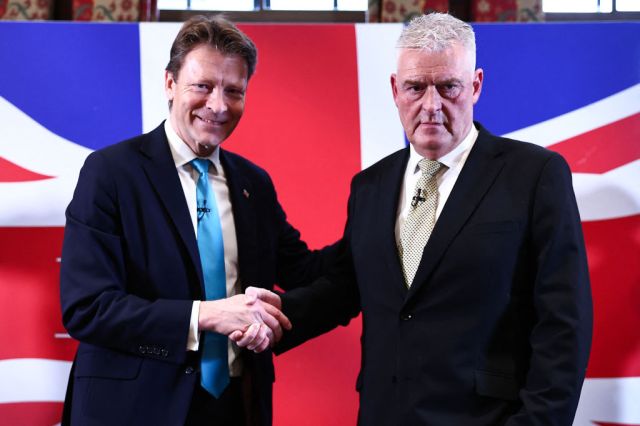

Lee Anderson (right) in March 2024 (HENRY NICHOLLS/AFP via Getty Images)

Something doesn’t seem quite right about Nigel Farage. We’re in the backseat of a car parked outside the Rifle Volunteer, and he’s just spent a solid hour in his element: shaking hands, grinning and taking selfies with supporters in Ashfield. Standing on an open-top bus in mustard-coloured trousers, he had announced a six-year plan to make Reform UK the biggest party in the country.

Hidden away from the din of excitement, I ask if he regrets not standing to be an MP. He mumbles something about the Tories shafting him in 2015, about the work he is already doing. And then a pensive silence.

It was, as we now know, scenes like those outside the Rifle Volunteer that prompted Farage to change his mind and stand for election. In his press conference last week, Farage mentioned the weekend he spent first in Skegness and then Ashfield. “Something is happening out there,” he warned. But what exactly? As the election circus pitches its tent in Clacton-on-Sea, a far better yardstick for Reform’s chances nationally — and Labour’s chances of building a dynasty — can be found in Ashfield, the home of Reform’s only current MP.

Squatting between Nottingham and Mansfield, Ashfield was once surrounded by coalfields. These days, it’s Amazon warehouses and quiet industrial estates. There are things called Library Innovation Centres, a planetarium built with Levelling-Up money and streets where people die 10 years younger than the rest of the country. In response to the statement “there is no political party I actually like”, only one constituency was more in agreement.

Come 4 July, it will be a three-way fight. For Reform, it is one of their top-10 targets; for Labour, a chance to prove they can win in a place where people still talk fondly of Boris Johnson. To complicate things, there’s also an independent candidate — Jason Zadrozny — who came second to Lee Anderson, then a Conservative, in 2019. A Brexiteer sympathetic to the 70% who voted Leave in the constituency, Zadrozny is, depending on who you ask, either a “corrupt nonce” or the “best thing that’s happened to Ashfield”.

The crowd gathered to see Farage and Anderson give a taste of Reform’s base in the area. “The red wall,” a Reform strategist tells me, “is not a geographical location but a feeling.” Many here dismiss cliches about the “left-behind”, the “somewheres”, and older disaffected working-class voters. Here middle managers, accountants and dentists rub along with builders and former miners; on age too, first political memories range from Arthur Scargill’s 1984 visit to Nigel Farage’s appearance on I’m a Celebrity. If this group is indeed united by a feeling, it is one of a nation on the brink.

“He says in public what everyone is thinking in private,” a woman in her 30s tells me when I ask her to explain Anderson’s popularity. “There are parts that used to be traditional. But now its kebab shops, vape shops, it’s completely lost its identity.” Suhael, in his 40s, points to people queuing up to take photos with Farage. “My friends would probably sneer at this,” he says. He, by contrast, is drawn to Reform’s hard-line stance on immigration: “I worry for the country’s future, particularly in terms of integrating newly arrived migrants. We came to this country for its Britishness but I feel that’s under threat.”

It’s a feeling shared by the tweed-jacketed Zoomers gathered to see Farage. “If you live in clown world long enough, then a backlash among the young is inevitable,” says Robert, 25, who plans to stand for Reform against Angela Rayner in Ashton-under-Lyne. He is representative of one of the more interesting polling developments that has got Farage looking ahead to 2029. Among 18-to-24-year-olds, Reform stands at 12%, with much made of his Zoomer-savvy social-media presence on TikTok. But it’s a phenomenon that only gently chimes with an electoral breakthrough on the continent, where a much bigger cohort is voting for Le Pen’s National Rally, Geert Wilders and the AfD.

I ask Farage if this is a continental model for his latest insurgency. He describes Europe’s Right-wing populists as “trailblazers”, but insists that “we want our own island brand”. Robert seems to agree with Farage when we discuss Jordan Bardella, the 28-year-old president of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally: “We are more controlled and less extreme in our views. We present them in a more positive way.”Sat in the Costa Coffee in Sutton-in-Ashfield, Jason Zadrozny rolls his eyes when I mention the gathering outside the Rifle Volunteer. After winning 28% of the vote in 2019, he is convinced he can become the populist doge of Ashfield. “People here have given up on party politics,” he says. “People are so angry with the Tories and are just voting Labour to get rid of them.” And this extends to Lee Anderson, with whom he has a long running feud. He claims Anderson begged him to join the Tories alongside him, bringing with him the strong connections to local businesses that has been the bedrock of his populist localism. He refused. He has since had to apologise for calling Anderson a “moron” in a council planning meeting. “Lee is an angry man pointing and shouting. He’s stuck in an echo chamber on Facebook.”

Zadrozny is leader of the council and one of the most successful independent politicians in the country. His localism is in many ways an end-of-the-pier tribute act to the ambitious but now seemingly tokenistic era of Johnsonian levelling up. An ice rink, a manufacturing centre and an observatory are his achievements (Anderson, he claims, didn’t want the latter which he described as “woke”). And he seeks a slither of that coalition who voted for the former prime minister in 2019. But such success is also overshadowed by allegations of corruption and cocaine possession, charges he insists are at the hands of embittered Lee Anderson’s supporters. “It’s like the Olympics; every four years they try to outdo last year’s accusations to bring you down.”

Out in Ashfield’s suburbs, meanwhile, Labour are busy knocking on doors of what desperate CCHQ strategists are calling “Whitby woman”. This is the older, home-owning Tory, let down by immigration, turned off by Sunak, and apparently enticed by proposals such as national service. Retaining her vote is key to stopping the annihilation of the Conservative Party.

Rhea Keehn is the Labour candidate trying to rub salt in the wounds by winning them over. A compliance officer who admires Harriet Harman and Yvette Cooper, she seems over eager to prove she will not go native in Westminster. “National politics, done locally” is her catchphrase, something she riffs on as she consoles elderly ladies who have had ornaments stolen from their front garden. Occasionally, between campaign speak, she will go off-script and say things like: “Smuggling gangs are mugging Britain off.” “I’m deeply proud to be British,” she makes a point of telling one woman after a long and painful conversation about immigration that stretches back to Tony Blair. Keehn is unable to convince her to vote Labour.

Do the people of Ashfield understand Labour’s vision for the country? Keehn and her fellow canvassers insist they do. And their endless list of Tory failures goes down well on the doorstep. “There’s toxic waste in Mablethorpe!” shouts one angry woman from her bedroom. But the name of the leader rarely comes up. In fact, it is hard to find anyone in Ashfield who likes Starmer or knows what his Labour government will actually do. “He seems to be like the others,” says one mum on the doorstep. “I can just tell there will be a lot of talk, but no follow-through.”

Come election night, Morgan McSweeney, the grand strategist of Labour’s campaign, will have a close eye on Ashfield. His manual for this election is Electoral Shocks: The Volatile Voter in a Turbulent World. It is a book that explains the political landscape of places like Ashfield: where partisan party affiliation is dead, folk memory of party politics is non-existent, and apathetic voters respond collectively to mass immigration and financial shocks. A big Labour win not just here, but also in 2029 and beyond, will be a test of the McSweeney project, which holds that the populism and apathy that defines Ashfield is not a product of “anxiety” in response to growing “openness’” of the world, but a measure of Labour’s disconnect.

And this is not just a disconnect to the “red wall”, but to the entire electorate. In Ashfield, after all, we can see extreme reactions to national problems that have only deteriorated since 2010: housing, immigration, the NHS and the cost of living. “Politicians don’t like coming here,” says Rob. “It’s too much a reminder of reality.” But they will have to come. Not just in the next few weeks, but over the next decade. For understanding the reality here is a precious political resource. In it lies the energy behind what are now the two defining movements in Britain’s politics: the future of its populist Right, and Labour’s plan to ensure it doesn’t have one.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe