(Belinda Jiao/Getty Images)

Within minutes of an election being called yesterday, the question on every broadcaster’s lips wasn’t whether the Conservative Party would lose in July — but how damaging the margin will be.

Labour’s current lead has a very wide range among pollsters, from 15 points (J.L. Partners) to 27 (YouGov). And yet, this does not tell the entire story: at the local elections, the BBC’s Projected National Vote (PNV) share pointed towards a single-figure lead for Keir Starmer’s party. So, as we stare down the barrel of a new election campaign, what explains these large gaps — and what is Labour’s “true” lead?

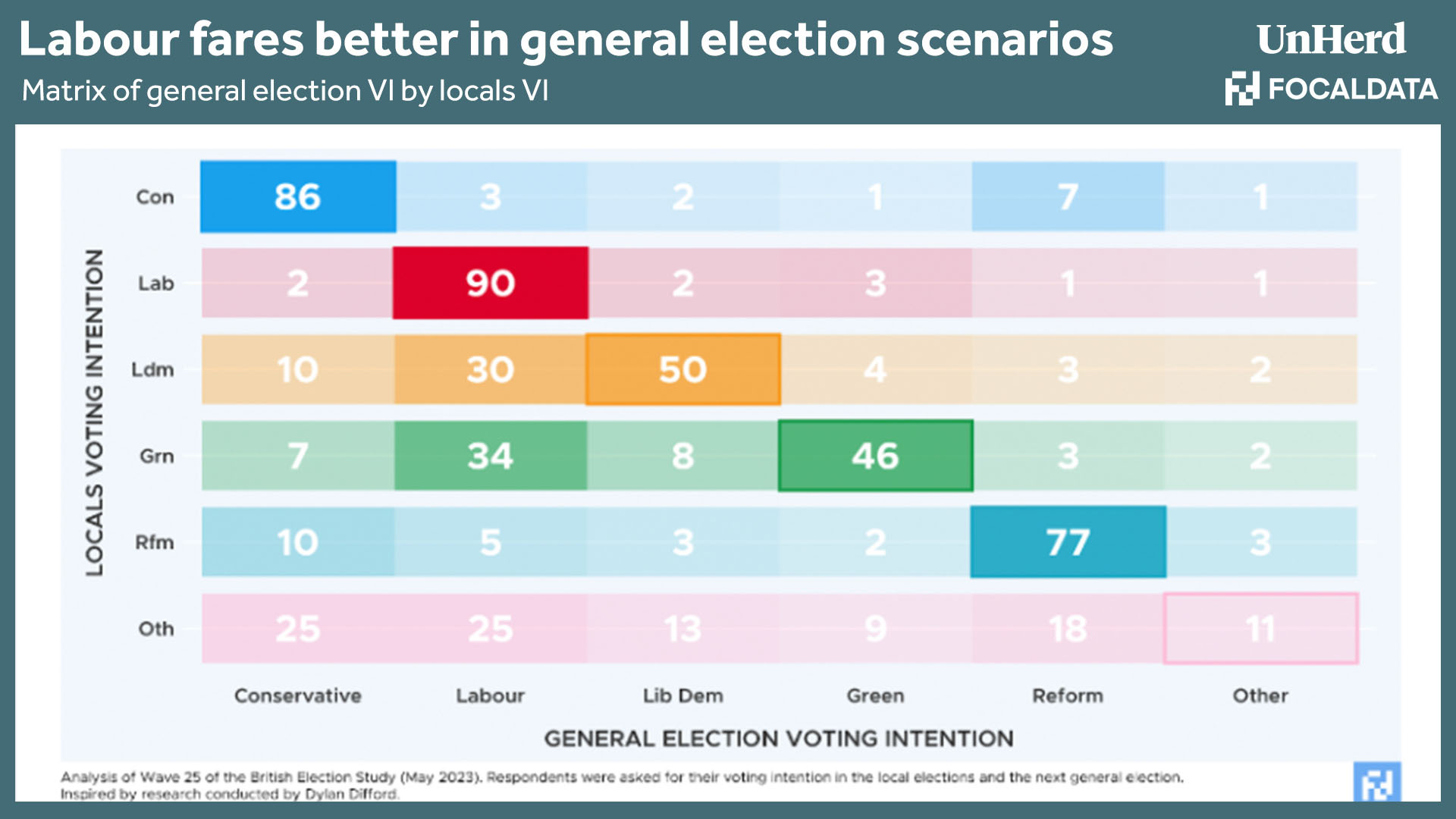

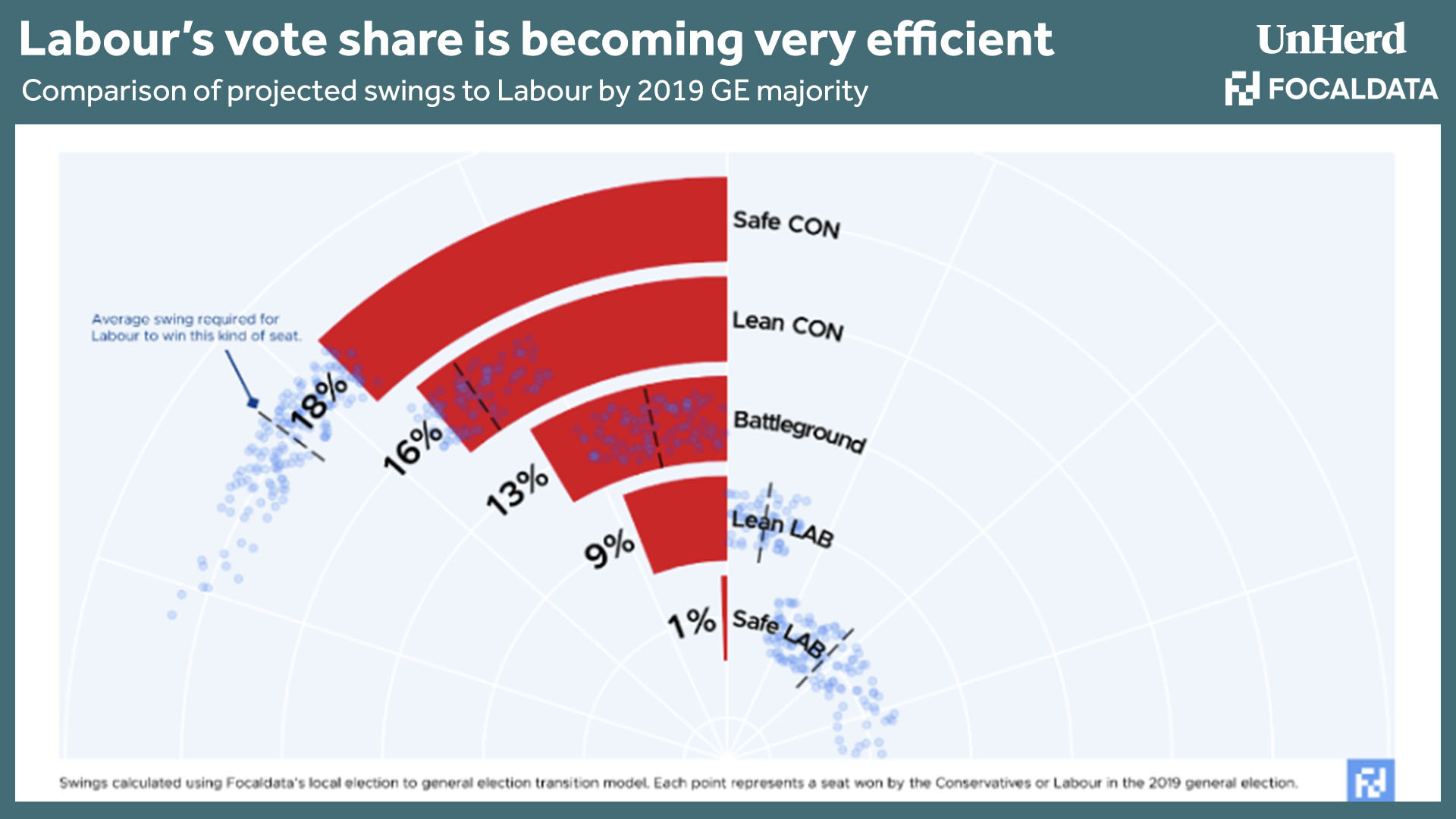

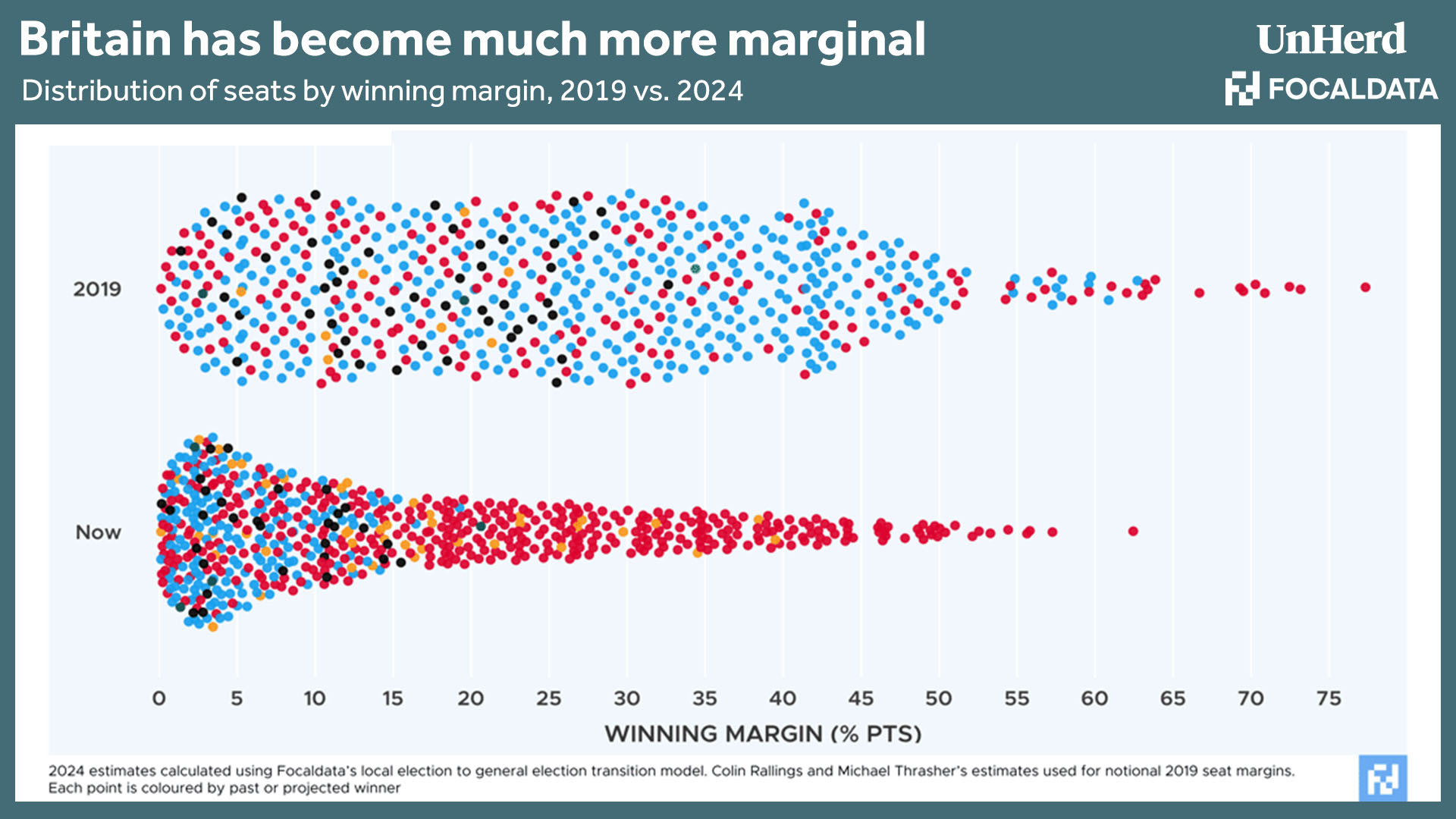

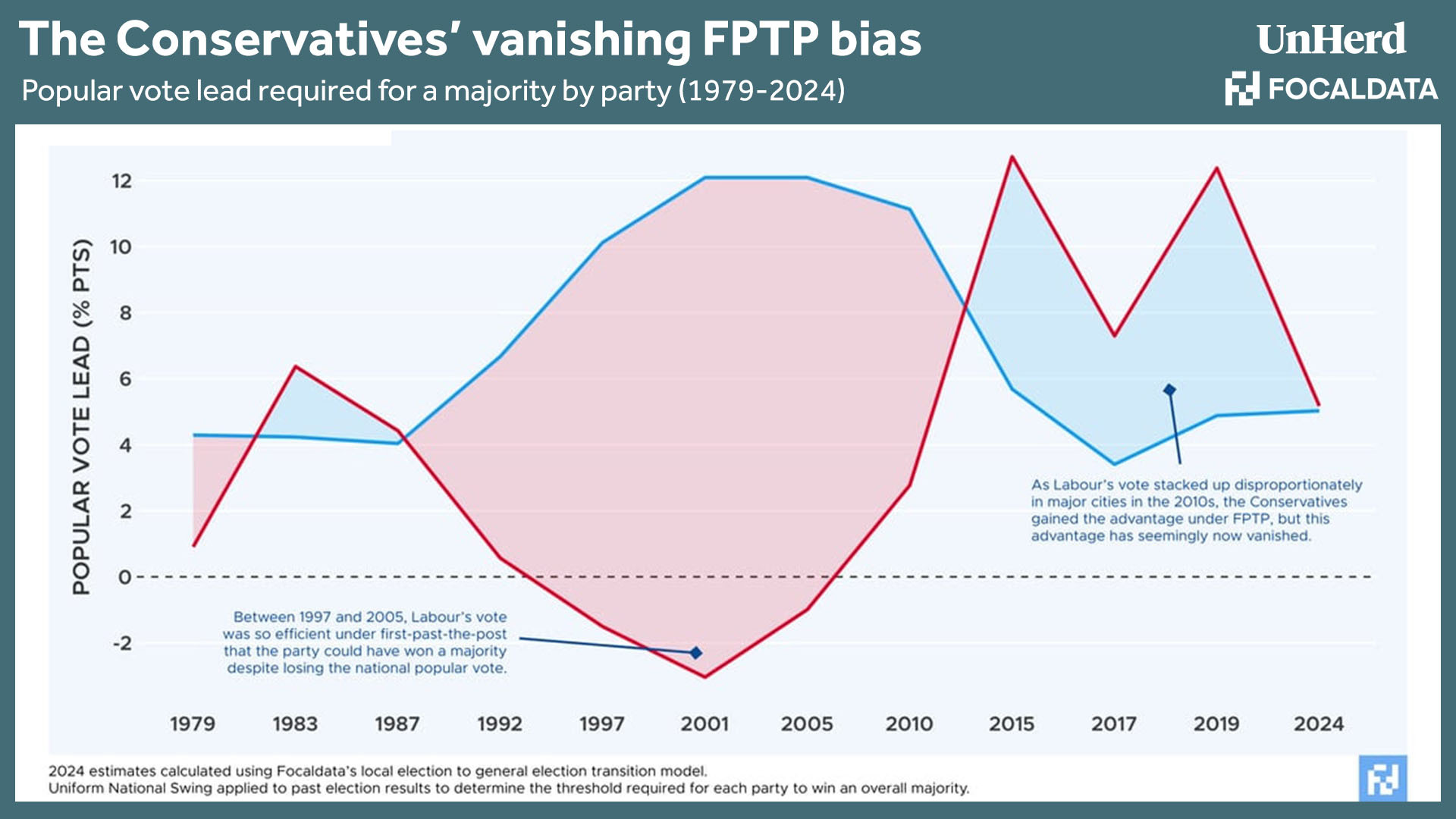

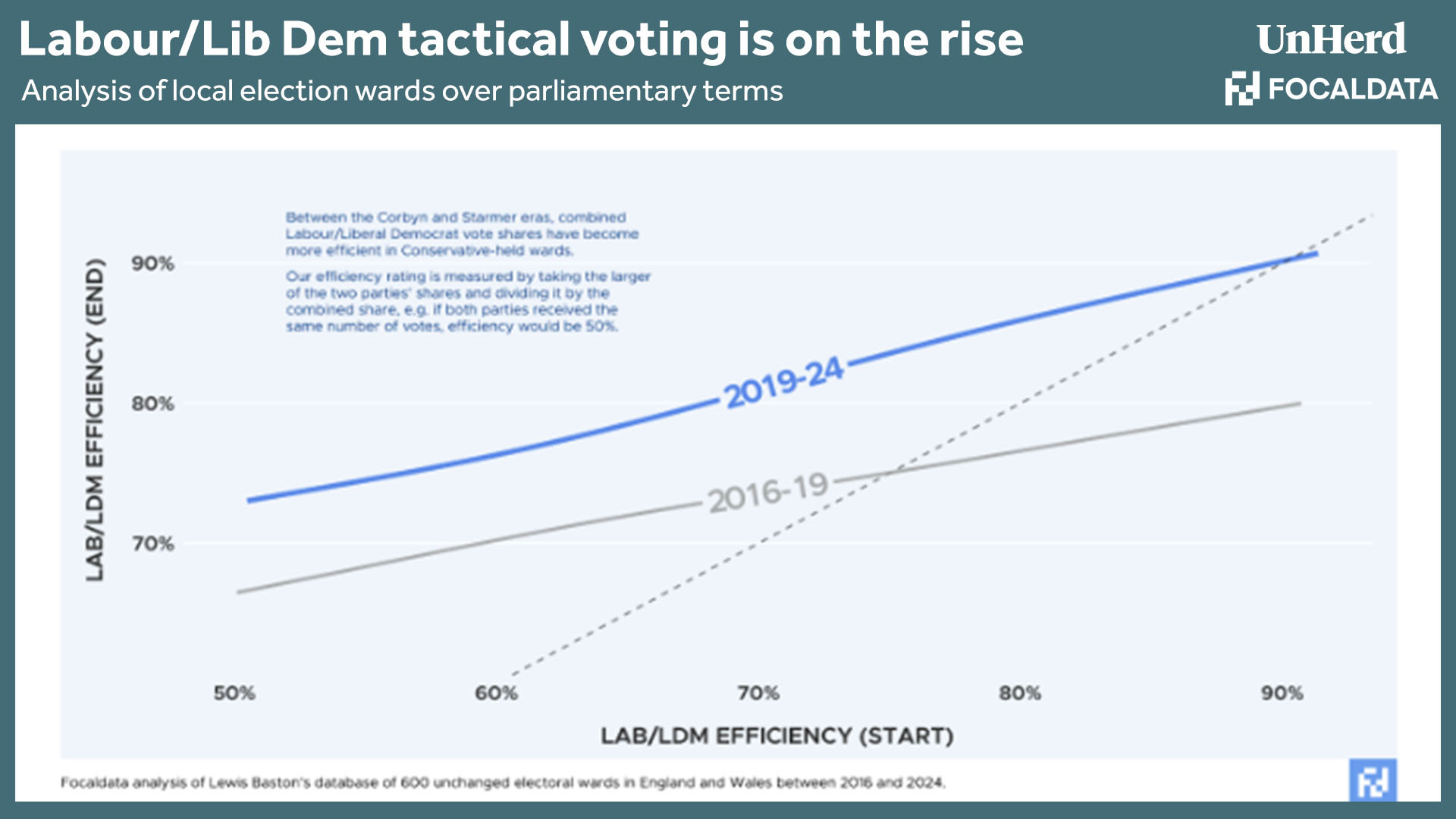

To answer this, Focaldata used this month’s local elections to project a general election result. And our findings may surprise you. They suggest that, for all the excitement emanating from Labour quarters yesterday, their popular vote is much lower than national polling estimates. However, thanks in large part to the efficient nature of the party’s current vote distribution, we believe Labour is still on course for a large parliamentary majority: we estimate that Labour needs a 5-7% vote-share lead to win, the lowest the party has needed to clear since 2010.

What is Labour’s “true” lead?

In the recent local elections, Labour’s lead over the Conservatives in the PNV share was nine points, with Keir Starmer’s party on 34% and Rishi Sunak’s on 25%. This is a much smaller lead than estimated by national polls.

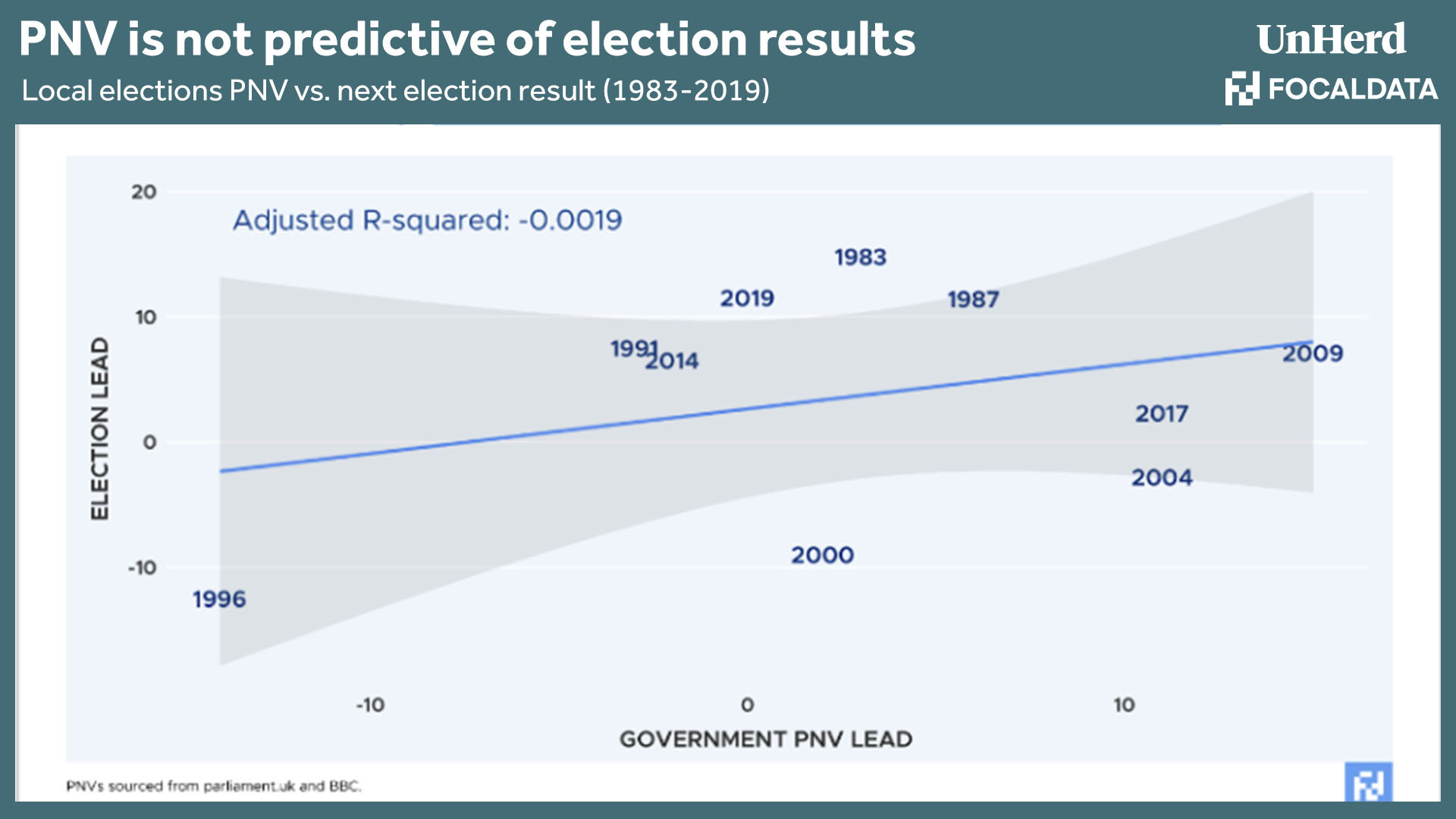

However, local election PNVs are not necessarily a useful metric for assessing how the country might vote in a general election. There is, history shows, very little relationship between the PNV in the set of local elections preceding a general election and the subsequent result. Our analysis of the past 10 general elections shows no provable relationship between local election PNV lead and final popular vote margin.

That being said, we think that the PNV is likely to be much closer to Labour’s “true” lead. National vote intention polls are “nowcasts” — glassy snapshots of current opinion — rather than forecasts of actual voting behaviour in a general election. Many assumptions that pollsters make to turn their polls into forecasts, including how they treat “don’t knows” and handle turnout effects, could be playing up Labour’s lead. In the month leading up to the local elections, for example, different pollster methodologies accounted for a full four percentage point difference in Labour’s vote share.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeThe only poll that matters is the one on election day.

Based on recent elections, it seems fair to assume that the political pundits will be wrong in their complacent assumptions again. It’s just not possible to know just how wrong they’ll be and in what direction yet.

I’d like to challenge myself to switch off all broadcast media political coverage for the next 6 weeks and only watch the results on the night. I’ll never do it, but think of all the time that could be saved and better used.

Wishful thinking, chums!

July will be an historic wipeout for the Tories – and richly deserved.

Two of the three prime ministers in this parliament will go down as amongst the very worst that Britain has ever seen. No-one will remember the third.

Prepare yourself for the sunlit uplands of Labour governments for a generation!

Shouldn’t that be gaslit uplands?

Gas will not be allowed under Labour.

I think you’d be wise to wait a few more years to see how well your lot perform before issuing the league tables.

But then you’re a socialist, so history is whatever you say it is !

Yay for more unsustainable immigration, pandering to every divisive minority cause, self-flagellation on nationality, net zero on steroids and no radical change whatsoever. Can’t wait to see the state of our democracy in 4-5 years time.

There will be no democracy in five years. The fake conservatives performance over the last five years was designed solely to ensure that Davos man/kneeler would be in place to deliver our country safely into the arms of Agenda 2030. All going to plan nicely.

I’d say that Labour’s lead is not as it seems, simply because there is no enthusiasm for them. The Tories deserve the public humiliation they’ve got coming, but let’s not pretend that Starmer is going to be cheered into Downing Street. I’ll be amazed if turnout is above 60%.

It all depends on how long Labour can go on simply not telling the truth about the climate, gender and immigration policies that they will inevitable introduce. I think there’s going to be a lot of buyer’s remorse as these become clear.

No, it’s a large anti-Tory vote on the table which doesn’t necessarily translate into the biggest Labour majority ever.

Sir Keir is even more insipid than Rishi and 6 weeks is more than enough time for the British public to become completely sick of the Briton most destined to be PM (after Boris).

Election night will be boring by about 2am when both parties are trying to explain why they couldn’t achieve what they claimed. The good news is that when the election AFTER comes, given both parties insane desire to decarbonise the grid rapidly. We won’t have any power to broadcast it.

Thank God I’ll be on holiday for much of June.

I never understood why Lib Dem voters think that Labour is preferable to Tories, I mean Labour is far more illiberal (in the original Classical Liberal sense not the Americanised version) and anti freedom.

I suspect that the Libs have become a blancmange centrist canvas now and no one knows what they really stand for anymore – certainly the old Whiggish sensibilities are long gone and the SDP part of Lib Dems seems firmly in charge now with Wera Hobhouse making it clear in recent years that voters should indeed tactically vote for labour and the Lib dems voting for the atrociously illiberal Hate Crime Bill in Scotland

We truly have very little choice these days…the least worst of a load of terrible options

Excellent comment – but I would apply your diagnosis to the Conservatives, too. The trouble is, people are adding Labour to this list of mushy centrists when they are in fact hard left. It seems to me, then, that this cannot be an election of positive choice; neither can it be an election of indifference – staying at home, spoiling the ballot, voting Green or Reform. No, it must be an election of negation – whom, then, to negate? Why, Starmer, naturally; and that means a vote for that floundering imbecile, Sunak. The trouble is, people are very unused to voting in this negative spirit. They have been indulged by all sorts of activism and political rage – PR, Scotland, Brexit, “Get Brexit Done” etcetera and they have forgotten that life is largely a choice of evils. With an evil as clear and horrible as Starmer in view, let us hope they recall this point in time. After all, using Sunak to stop Starmer today in no way prevents us from using the subsequent reprieve to set up a real challenge from the right – and under FPTP this can only be done constituency by constituency. Finally, to all those thinking that a Reform vote is the answer, such as the plump and fruity historian who works for the NCF, I say this: your own diagnosis – “right wing voters are dying at a rate of two per cent a year” – means that the nuclear of option of “let Starmer show them how awful the left can be – is a non-starter. The indoctrinated, bought up, apathetic populace of today will never, repeat never rebel. The very fact that so many are planning to spoil the paper or stay at home means that rebellion is off their radar. So the “lesser of two evils” argument is – quite literally – our only hope.

Well I’m a Labour voter but they’re going to win anyway so I’m going to vote Reform in my safe Tory constituency. Probably. My vote is irrelevant.

Unbelievably insipid, Sir Keir, ripe only for leadership by Washington neocons and the European Central Bank in Frankfurt.