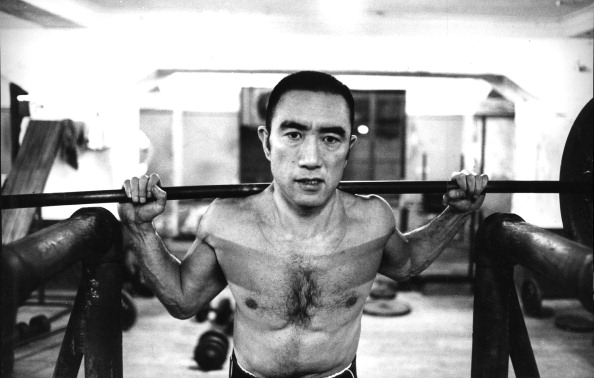

How has this short man become a masculinity icon? Credit: Mario De Biasi/Mondadori via Getty Images

In some ways it’s strange that the online bodybuilding community idolises a slender, unathletic, literary youth. But given his knowledge of weakness, Yukio Mishima, real name Kimitake Hiraoka, understood the addictive pursuit of strength.

Mishima examined strength and weakness in some of the greatest works of 20th-century literature. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956), for instance, tells the story of a pathetic, dissolute son of a consumptive Buddhist priest, growing up amid the wartime wreckage of mid-century Japan. The protagonist, Mizoguchi, experiences various indignities while descending into mental illness, culminating with a suicide attempt he ultimately abandons, choosing life instead.

Mizoguchi is based on Mishima’s study of a real-life Buddhist acolyte, Hayashi Yōken, who burnt down the titular pavilion. Albert Borowitz described the arson in his 2005 book, Terrorism for Self-Glorification, emphasising that Japanese authorities attempted to conceal Yōken’s name, for fear of him achieving national celebrity. This anti-hero’s weakness — and resulting madness — arises within the context of a society perceived as both impotent and decadent; striking parallels exist between him and today’s hapless, bullied mass shooters, such as Elliot Rodger and, more recently, Anderson Lee Aldrich.

But Mishima is most often invoked by online admirers in 2022 not for his literary greatness or political insight, but his personal aesthetic. He was, for want of a better word, ripped — lean and well-defined from the practice of weight training, karate and kendo, which he undertook because he wished to experience “the essence of action and power”. The Mishima of the Western cultural imagination, then, is similar to the Oscar Wilde who allegedly told André Gide in Algiers that he put his genius into his life, and only his talent into his works.

It was a life that ended with a picture-perfect tableau: a ritual suicide, alongside a 24-year-old male follower, in the office of a commandment of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, where he had attempted to initiate some sort of national — or at least nationalist — renewal by means of a carefully stage-managed coup. Latter-day dissident intellectuals such as Bronze Age Pervert, writing in Bronze Age Mindset, understand Mishima’s appeal: “A beautiful death in youth is a great thing, to leave behind a beautiful body, and the best study of this pursuit you find in the novels of Mishima, a real connoisseur.”

Mishima’s perfect body was based on both a Western sculptural ideal, rooted in Greco-Roman ideals of beauty, and “silence”: the pull of a “wordless body, full of physical beauty, in opposition to beautiful words that imitated physical beauty”. Language, the stuff of social media posts, hot takes, and the political opportunists running our country, seems to exist to conceal and deceive; Mishima sought the “pure sense of strength” — some ideal that would tether him, body and soul, to “ultimate reality”.

He dreamed big, then. But materially, Mishima was limited. This much is obvious from the 1960 film Afraid to Die, in which he played the starring role as a gangster. He makes a display of leather-clad toughness, chest puffed out as far as his well-defined but concave pectorals can go. But it is almost a camp toughness, a little boy strutting and fretting along the stage in tough-man drag. Mishima, all of 5’4” on tiptoes, is no swaggering Marlon Brando or Burt Lancaster. From the perspective of a functional strength athlete, it is bizarre that he commands so much attention. And yet there he is, even if he is in “hyper-masculinity drag”, admired by all manners of weightlifting intellectuals and dispossessed dissidents.

It is this quality of Mishima that reveals something unexpected about the muscle boys of 2022. His modelling — artistic, sensitive, and even quite beautiful when working with photographers like Eikoh Hosoe — conveys in most cases not pure strength but a body that has “transitioned” to be more masculine. It is an end result that is at least stronger — if not as strong as it appears — frozen in time by the camera. The images for which Mishima sat, like the ritual death for which he spent years preparing, is somehow more important to his contemporary acolytes than the day-in, day-out life he actually led — which is exactly how Mishima would have wanted it.

If this sounds bizarre, consider a quotation from the Washington Post’s recent series on the dangers of excessive steroid and diuretic use in bodybuilders. Mike Israetel, a 38-year-old bodybuilder who holds a PhD in sports science, described why he has used steroids for the past decade: “I’m almost to that size…[where] these are pictures that I’ll have forever, that I can look back on and say: ‘Wow, I really did the thing. I really looked the part, like the part that I was truly capable of looking.’” In other words, Israetel has built his body expressly for the pictures, so he can see himself looking the way he wished to be.

This was the same desire that provoked Samuel Fussell, a slender, dissipated academic, to take up the “steel” in the late Eighties. In his memoir Muscle, he describes how he pursued the creation of a new body, abetted by steroids, to serve as a hyper-masculine self that he portrayed to the world. Behind it, he could hide whatever remained of his real self. “Everything I’d done for the last four years had been an effort to keep the world at bay, to find a place in which I wouldn’t have to react or think or feel,” Fussell wrote of his transformation. His body grew far larger than Mishima’s or even Mike Israetel’s. But, he wrote, “as big as I’d gotten and impressive and imposing as I looked ‘standing relaxed,’ I felt that if you could somehow find a chink in my armour… you’d find nothing within that vast white empty space but a tiny soul about the size of an acorn.”

In my many years of interviewing bodybuilders, I’ve seen this philosophy crop up a lot. When I spoke to the long-time pro Bob Paris, who during the Eighties and early Nineties married considerable mass with Frank Zane-calibre aesthetics, he told me that putting on a “gorilla suit” — the title of his memoir — provided, among other things, some cover for the homosexuality he wouldn’t disclose to the world until the early Nineties. “I hated myself”, he wrote in his memoir. “My limbs were all in the wrong places, my teeth were weird, the hair on my head from outer space, the hair sprouting on my chest embarrassing. And I was a fag.” Or, as he summarised it to me: “What’s the old saying? ‘Show me a bodybuilder and I’ll show you a guy with dad issues.’”

Mishima, Israetel, Fussell, and Paris all wished to be seen, and see themselves, in a certain way. But the latter two renounced this pursuit in their memoirs. Both continued to train for health and general fitness, but they have lost their will to discipline their bodies in pursuit not of functional strength but some sort of particular image. As Fussell put it when he walked away from bodybuilding: “My lifting was life-denying rather than life-affirming… I was a lonely and solitary sceptic in this realm of smiling and pumped Pollyannas.” Paris was more emphatic: “At the end of my bodybuilding rainbow, instead of a pot of gold, there was a complication; beyond that, frustration.”

These patterns of thought have appeared in many of the other interviews I’ve done, too. When I spoke to a 20-something gay software engineer named Zander, who was using heroic doses of steroids to become the “muscle bear” of his dreams, he put the matter succinctly, drawing on the language of gender identitarians: “I sometimes see the use of steroids by men as like, being assigned male at birth, but identifying as even more male than your natural physiology would allow.”

He then put the question to me directly: “In a world in which we were truly free to express our gender identity, would you be able to get prescribed supraphysiological doses of testosterone to fix the persistent feeling that you were not manly enough?”

Zander, like Mishima and Fussell, grew up weak and badly out of shape; his “transition”, which mirrors the one described by Mishima in his essay Sun and Steel, albeit with steroidal intervention, was an identity overhaul for him. It was, moreover, not something I understood, despite my years of lifting: I was a big kid, with a big father who had been a big-time athlete, and bigness and its attendant qualities, such as strength, was something I took as a given, until beginning to write about it decades later. I never had the experience, as California mass shooter Elliot Rodger wrote in his 2014 manifesto, of losing a trivial martial arts contest to a boy “who was so much physically stronger than me” that even “the deep anger inside me” couldn’t close the gap. It was, in other words, utterly alien to my own experience of masculinity, which I rarely considered; it was what it was, for good or ill.

Zander’s earnest discussion of this process, less artistic by far than Mishima’s analysis but equally heartfelt, calls to mind psychologist J. Michael Bailey’s treatment of “autogynephilic transsexuals” in his 2003 book, The Man Who Would Be Queen: “Autogynephilic transsexuals might declare attraction to men or women, to both, or to neither, but their primary attraction is to the women that they would become.” Could Zander and Mishima and all the others so obsessed with his idea of presenting the image of masculinity, indeed of hyper-masculinity, be “auto-androphiles” of some sort: individuals primarily attracted to the men they would become?

After 20 years of work in the strength and fitness world, I believe there is an important parallel to be drawn here. One often (but not always) finds that individuals making this sort of transition to hyper-masculinity are bitterly opposed to those going in the opposite direction — viciously critical of transgender females, in other words. Yet in their attraction to the men they want to become, there is a great deal of similarity: both are in love with the “hyper” aspect of their own mirror (or selfie)-reflected performances, whether it be hyper-masculinity or hyper-femininity.

Bodybuilders, from the anonymous model for the Farnese Hercules in the early third century AD, to ever-accelerating, the strongman Eugen Sandow in the early 20th century, have always shown off the fruits of their labour. But the technology of 2022 lets us go far beyond that, to admittedly unhealthy extremes. The narcissism of the present age is evident in an obsession with not just images but total control of the image. (Of course Mishima has become an icon: he stage-managed his own death.) Now cameras, filters and even AI art can take us even further; we are awash in self-love, on as many screens as possible.

Of course, wanting to be stronger is a reasonable goal: as strength coach Mark Rippetoe told me when I spoke to him, strength is preferable to weakness, even if “six-pack abdominals” matter little with regard to functional capacity. But when it crosses the line into disordered gender performance, it loses any such claim to utility. Even the old guard of ostensibly aesthetics-oriented bodybuilders recognise this. When I interviewed Frank Zane, perhaps the most aesthetically-minded bodybuilder of all time, he told me he had little use for selfies or heavily edited photography because they prevented the objective feedback that a picture simulating real-life conditions could provide. A man’s body, he told me, is a well-oiled machine — not a fantastically distorted ideal that one presents as standing in for something greater, but a functional construct that had to be seen up close and assessed in real life.

That level of what-you-see-is-what-you-get objective reality, not Mishima’s “ultimate reality” or the “hyper-masculinity” of the auto-androphile, served for Zane as the natural limit on aesthetic flights of fancy. It is a boundary, I think, that young men looking to build strong, healthy bodies would be well served to keep in mind.

***

Order your copy of UnHerd’s first print edition here.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe