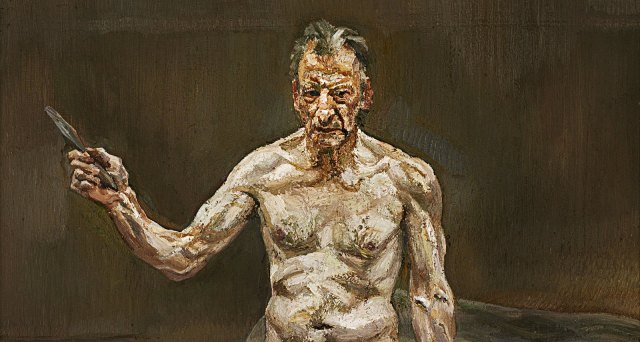

“Painter Working, Reflection,” 1993 (The Lucian Freud Archive/Royal Academy of Arts)

In late 1940, the 18-year-old Lucian Freud sent a series of highly decorated letters to the renowned poet and critic Stephen Spender. The pair had become fast friends and, despite their 12-year age gap, would later become lovers. In their exchange — one of many collected in the brilliant new volume Love Lucian — Freud embellishes his messages with pencil illustrations and not-so-subtle hints of their growing romantic attraction; Freud gave himself a pen-name meaning “juicy fruit“.

Their correspondence is remarkable not just for the intimacy it reveals, but for the fact that the volume exists at all: while Freud was alive, none of these letters would have seen the light of day. He was obsessively, obstreperously concerned with his privacy. One biography was halted after Freud felt too disconcerted by its revelations, and another was stopped at Freud’s behest by the very persuasive presence of a group of East-End gangsters. The first volume of William Feaver’s weighty account was only published in 2019 — eight years after the artist’s death.

Martin Gayford — who edited the new volume with Freud’s long-term assistant David Dawson — was uncompromising about how Freud would see this latest book: “I’m sure he wouldn’t have welcomed it… [but] posterity is owed the correspondence.”

It’s not hard to see why an intrepid writer would run the risk of Freud’s wrath or even hired violence. Freud’s life is made for a biography. The grandson of Sigmund Freud, he was born in Berlin and moved to London to escape the rise of Nazism in 1933. He dated Greta Garbo, danced with Marlene Dietrich, was friends with Frank Auerbach and Francis Bacon, married the sculptor Jacob Epstein’s daughter, Kitty (after an affair with her aunt), eloped with the Guinness heiress and socialite Lady Caroline Blackwood, and, in his later years, was friends with the supermodel (and future subject) Kate Moss. He dated the artist Celia Paul — after having met her when she was his student — and had scores of other mistresses. He is the acknowledged father to 14 children, and the suspected father to dozens more.

It is this celebrity — his “fame and infamy” — that the new retrospective at the National Gallery, Lucian Freud: New Perspectives, hopes to “look beyond”. The exhibition’s curator, Daniel F. Herrmann, writes that Freud’s artistic practice has been “overshadowed by biography”, and he hopes to bring the paintings back to the fore.

It’s a worthy aim — who doesn’t want an art exhibition to be focused on the art? — but, when it comes to Freud, the line between biography and creation has always been rather fraught. After his early portrait of his art teacher and friend Cedric Morris (Love Lucian also features letters to Morris), Freud rarely painted portraits of named sitters. His pictures of his first wife, Kitty Garman, often refer to her only as “girl”: Girl with a Kitten (1947); Girl with a White Dog (1951 – 1952); Girl with Roses (1948). Garman may have been Freud’s muse, but he was meticulous about keeping her name, and any hint of their joint biography, out of his work.

This anonymising impulse continues throughout Freud’s work: his first portrait of a male nude is called Naked Man with Rat (1977-8). There is no mention of the man, Raymond Jones, who took off his clothes and sat for hours and hours at a time with a drugged rat next to his naked testicles. (To keep the rat still during the painting, Freud fed it champagne mixed with sleeping pills. As if the scene couldn’t get any more surreal, Raymond recalled how Freud used to stop painting to have sex with his girlfriend in the bathroom next door, and would come back having had a “bath to settle [him]self down”.)

Even the nobility — Freud liked to claim he moved “vertically” through society from wheelers and dealers to the Royal Family — did not avoid his anti-biographical impulse. In her 1957 portrait, the 11th Duchess of Devonshire, Deborah, is only given the name Woman in a White Shirt.

But it is not just his painting’s anonymising titles that seem to simultaneously invite and deny discussions of biography and celebrity. Freud’s characteristic style is also marked by an almost clinical detachment. His sitters are subjected to his excoriating gaze, and the final products seem to treat them more as observed animals or inert carcases than humans.

Take his 1995 work Benefits Supervisor Sleeping. It is a brilliant painting of “Big Sue” Tilley on a cream and floral sofa, with the heft and weight of her body falling naturally towards the painting’s bottom edge. Her flesh is uncompromisingly, brilliantly realised — Freud was a master of tone, and it is possible to see the tangible difference between the soft squish of her stomach and the knobble of her knee. Yet for all this brilliance, the painting is unbelievably disconcerting. It is notionally a painting of “Big Sue” asleep, but the cold, unsparing nature of Freud’s gaze makes her seem dead. Is there a chance this is a corpse? If her left arm weren’t raised and holding on to the back of the sofa, it would be all too easy to think so.

It is, of course, the other aspects of Freud’s life — the model-firing; the bread-roll-throwing; the general stroppiness — that the curators of the new exhibition want to “move beyond”. And they have a good point: once you hear of some of Freud’s behaviour, it’s hard to look at his work in the same light. Look at his “naked portrait” — Freud hated the word “nude” — of his 18-year-old daughter Rose Boyt, Portrait of Rose (1979). It’s an unashamedly sexual picture: Rose is lying back on a sofa, with her arms raised and her legs apart. Even MailOnline insists upon pixelating the area between Rose’s legs. The picture has caused a stir ever since it was first exhibited, but, after reading how he once shouted across a restaurant that “women should smell of one thing: cunt — in fact, they should invent a perfume called cunt”, it’s even harder to brush off an all-pervasive sense of his chauvinism.

This anecdote was just one drunken outburst — and it is unlikely Freud ever imagined it being used in criticism of his work. But it is part and parcel of a picture of a man who could be uncompromisingly cruel, just as much as he could be ostentatiously generous. In his biography of the artist Breakfast with Lucian, Geordie Greig draws attention to this uglier side of Freud’s character: he could be anti-Semitic, despite being Jewish himself; he railed against waiters for assuming he was gay when he was out with another male friend, despite having had homosexual affairs; and he was continually getting into altercations in bars and restaurants, even when he was elderly.

But however scandalous these stories are, they only really lead us back to one, boringly hackneyed, question: how far can you separate the art from the artist? It’s almost a moot point. You can feel Freud’s cruel, uncompromising, brilliant gaze in every canvas — and the paintings do not get worse, or better, when you hear sweet stories of him drawing pictures for children, or being unbelievably unpleasant to his mistresses.

There is one person for whom there was little difference between Freud the artist, and Freud the man. The artist Celia Paul was Freud’s student, and had a relationship with him for a decade. Paul sat for many of Freud’s paintings and has written, beautifully and eloquently, about the pain of being his “muse” (she hates that word) in her two books Self Portrait (2019) and Letters to Gwen John (2022).

Paul has recently painted a work called Overshadowed — a large portrait which is on show at an exhibition in Victoria Miro until 1 October. She has painted herself seated, staring out at the viewer with her hands clasped. But when I speak to her, she draws attention to the fact that it isn’t a simple self-portrait: “I have painted myself as a painter.” The work is a response to the Renaissance artist’s Sofonisba Anguissola’s Self-Portrait with Bernadino Campi (1559), in which all power balances are upended: Anguissola is being painted by her teacher, but she appears to be in charge. In Paul’s words, she “guides Campi’s hand as he appears to paint her”.

Paul wanted to do her own version of Anguissola’s painting — “Campi was Anguissola’s teacher as Freud had been my teacher and lover” — and “placed Lucian on the left of the composition”, using his self-portrait as a guide. But the result was “too illustrative“, and Paul rubbed him out. All that is left is his ghostly shadow. The resulting work is quietly, inordinately powerful. It is about looking, concentration, and focus; and it’s also a reversal of the expected power dynamic. Paul is seated, smaller than Freud’s shadow, but her gaze leaves no ambiguity about who is in control.

This is a work which plays with the shadow of biography — letting it hover; fade; and be present despite its absence. It is, wonderfully, the antithesis of many of the impulses in Freud’s work. Perhaps better than any exhibition, it succeeds in trying to “move beyond” biography; the unseemly, ungainly elements of Freud’s life. Here, in Paul’s painting, is proof of the power of letting them linger, overshadowed by her own talent.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe