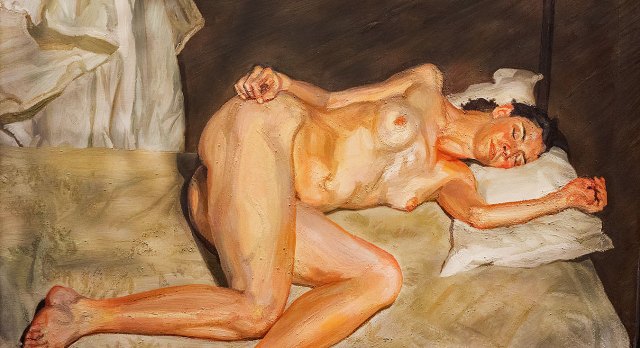

What’s she up to now? Credit: Chris J Ratcliffe/Getty Images for Sotheby’s

“One of the main reasons I want to speak to you now is because I’ve become increasingly aware of how both of us are regarded, in relation to men,” writes the artist Celia Paul to the late Welsh portrait painter Gwen John.

“You are always associated, in the public’s eyes, with your brother Augustus and with your lover, Auguste Rodin. I am always seen in light of my involvement with Lucian Freud,” Paul continues. “We are neither of us considered as artists standing alone. I hate the term ‘in her own right’ — as in ‘artist in her own right’ — because it suggests that we are still bound to our overshadowed lives, like freed slaves.”

They may have painted remarkable portraits themselves, but both women are primarily known as the muses of “great” male artists. And Paul’s new book takes the form of a series of letters to John, whose life was “stamped with a similar pattern” to her own.

“I hate the word ‘muse’, too, for the same limiting reason … What is it about us that keeps us tethered?” Paul undoubtedly knows the answer to this question already: she is forever seen first and foremost in terms of her association with a man, rather than judged by her own successes.

When the National Portrait Gallery, for instance, recently acquired a self-portrait by Paul (“Portrait, Eyes Lowered”), each of the news articles emphasised her “relationship with Lucian Freud, who painted her many times”. Similarly, Rachel Campbell-Johnston chose to open her Times article with the very same framing the artist despises: “Celia Paul was a model and muse for Lucian Freud. She is also an artist in her own right. There . . . I’ve said it. That’s how Paul does not like to be introduced.”

This rhetoric is not unusual: there is a long history of women being identified as partners of men, rather than as individual agents. Constance Mary Lloyd was a children’s book writer and dedicated activist who campaigned for a woman’s right to serve in parliament. But, upon marrying Oscar Wilde, she was referred to as “Mrs. Oscar” in the press.

This is particularly galling when a woman has been instrumental to her partner’s success by, say, serving as a muse — a role whose influence has been repeatedly denied by male artists. Some have actually demanded that muses who were practising artists forget their careers to exclusively serve them. We know the famous faces of these women but often nothing of their own art. Jo Nivison Hopper, for instance, frequently features in her husband’s cinematic paintings, including the downtown diner scene, “Nighthawks” (1942). Most people recognise this painting; but how many could call to mind one of Nivison’s?

Nivison was initially the more successful artist. In 1924 she was invited to show six watercolours at the Brooklyn Museum, alongside Georgia O’Keeffe and John Singer Sargent. Meanwhile, Hopper hadn’t sold a painting in over a decade. Nivison, wanting to support Hopper, convinced the museum to include his work in the show; this was the exhibition which launched his career, and ended hers.

That same year, Jo Nivison married Hopper. From this moment on, her diary tells the story of his abuse, which was physical as well as psychological. Her husband discouraged her from painting: “If there can be room for only one of us, it must undoubtedly be he,” she writes, assuming the role of studio assistant, secretary and muse, and sacrificing her own success for Hopper’s.

Paul intersperses her letters to Gwen John with reflective passages; they reveal that her fate contains distressing echoes of Nivison’s. Freud attempts to control and exploit Paul; he suggests that she should act like Gwen John, who gave up her own work while having an affair with Rodin:

“He often compared me unfavourably to Gwen John. He told me how beautiful he thought it was that she stopped painting when she was most deeply in love with Rodin because she wanted to give herself up entirely to the experience. She told Rodin, ‘I am not an artist, I’m your model, and I want to stay being your model for ever. Because I’m happy.’ This is how Lucian would have liked me to be. He would have loved Gwen.”

Freud’s desires reflect wider societal expectations that women should serve men’s needs above their own. Nevertheless, Paul — in contrast to John and Nivison — refused to acquiesce to Freud’s demands, living on her own and, following the birth of their son, passing childcare duties to her mother. She reveals that she always felt “resentful” about wanting to be with Freud, as it meant spending less time on her own work.

Perhaps Paul hates the term “muse” so much because she was forever attempting to evade the role — which is a demanding one. As she has said before, “the act of sitting is never passive”. She didn’t have the time, motivation or energy to be Freud’s full-time muse, if she was to become a successful artist on her own terms. “He wanted active participation”, and she wasn’t prepared to surrender. Which perhaps makes it all the more infuriating that being Freud’s muse is so often seen as the most important thing about her.

Still, for someone who is so enraged by the term, Paul can’t quite seem to (or doesn’t want to) completely let her identity as Freud’s muse go. In her letters she dwells on the decade in which she was “intensely involved with” the painter. And it’s not the first time that he has been her subject on the page. Her first book, Self-portrait, focused on her 10-year relationship with Freud, from meeting him while a student at the Slade (she was entranced by his “eerie glow”) to the first time she posed for him and cried. Throughout, she chronicles her struggle to love someone while dedicating herself to painting.

Having already told, and sold, her story as Freud’s muse, isn’t it about time that Paul moved on — especially if she wants everyone else to? Though professing to “hate” being seen always in relation to Freud, isn’t Paul also mining that association? In her letters to John, she is still reflecting on their “connection”, which she can’t seem to break. And in her paintings, Paul continues to orbit Freud. For her show at the Victoria Miro in 2019, she submitted an intimate self-portrait, “Lucian and Me”, in which the male painter tilts his head towards her, as if about to whisper a secret in her ear; she, too, leans in.

Does Paul want it both ways? She is complaining about the plight of the muse, while attempting to profit from that status, effectively cashing in on her association with Freud. But then, why shouldn’t she? Paul, like so many other female artists, has been overlooked and exploited by the patriarchal art world. Why not take advantage of a situation she can’t escape, even when she tries?

“The world celebrates and rewards women who are chosen by powerful men,” the model Emily Ratajkowski pointed out last year in her memoir, My Body. No matter what she does, she will forever be known for her debut: dancing nearly naked in the music video of Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines”. It is practically impossible for women to escape the association, and influence, of the male gatekeepers who have “made” their careers; all they can do is try to reshape the narrative about their origins. Knowing that, why should we judge Ratajkowski because, to use her words, “I’ve capitalised on my body”?

Paul, too, has been placed in an impossible situation: no matter what she does, she will be seen as Freud’s muse first and an artist “in her own right” second. Paul may as well, then, leverage this association with Freud to further her career, and identify with other women like John who have also been framed in this light. It’s clear that she, like Ratajkowski, is using the very connection that binds her for her own means.

And yet, there is more than self-aggrandisement at stake. Paul is not simply feeding the reader’s fascination with the artist-muse relationship and name-dropping Freud; she is also turning the tables on art history.

In another self-portrait, “Painter and Model” (2012), Paul sits with tubes of paint at her feet, in a huge, stained overall. She is, unmistakably, the painter. But the title coyly alludes to the lasting impact Freud, though he’s not present in the painting, has had on her life. So much so that the viewer is left wondering: is Paul’s final project to invert their relationship? Here, she is the protagonist, while Freud has become a supporting character in her story: an invisible muse.

Ruth Millington’s book, Muse, is published this month.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe