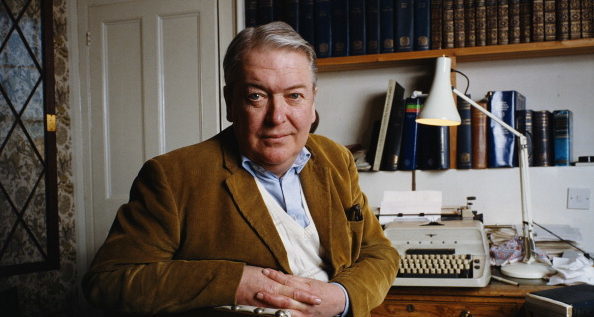

Bryn Colton/Getty Images

Close to my home stand two glorious late-Victorian monuments to what the preachers of the age would have called the beauty of holiness. A few minutes’ walk in one direction takes me to St Augustine’s, Kilburn, decorated with exquisite murals and topped by the architect J.L. Pearson’s proudly soaring spire. Another Gothic Revival masterpiece lies a little to the south: G.E. Street’s St Mary Magdalene, Paddington, breathtaking in its command of space and volume, and enriched within by splendid glass and carving.

Built amid London’s squalid slums or ragged suburbs, both Anglican churches remind you that the Anglo-Catholic clerics and artists of their time believed that nothing was too good for the people they aimed to serve. They plundered the high-medieval styles of France, Italy and Germany to plant islands of awe and majesty in the midst of urban grime. The toiling masses needed sacred beauty as much as they needed bread. Indeed, these neo-Gothic visions and missionary Christian Socialism often went hand-in-hand. Such retro grandeur also gave voice in brick and stone to another powerful yearning: a wish that the Protestant Reformation had either never happened, or else had not led to a permanent schism — and that the English church had stayed firmly within the fold of undivided Christendom.

Such Romish nostalgia might now look like a niche interest. But its secular legacy lives on: for instance, in the attraction of a variety of home-grown Europeanism that pines for a profound connection not so much with some suited bureaucracy in Brussels as a continental mainstream of art, thought and culture, without which England will wither into petty provincialism and insularity. Much of the time I share that longing, although I know it has tangled roots. And, surprising as it may seem, an outlier work by the foremost English comic novelist of the later 20th century expresses and dissects it with enormous empathy, mischief and wit. That work is Kingsley Amis’s 1976 novel The Alteration.

Amis was born a century ago, on 16 April 1922. The eclipse of his reputation means that any anniversary jubilations will have been muted at best. According to a now-standard version of his life, the maverick outsider satirist of Lucky Jim subsided fast into grumpily reactionary provocations spiced with heavy-duty boozing, serial adultery and (in his later fiction) spasms of venomous misogyny. Others can draw up the charge-sheet or plead for mitigations. I’m convinced merely that The Alteration — mid-period Amis, written when his decline into blowhard cynicism had supposedly taken hold — deserves to endure. It succeeds not only as a wildly imaginative, vastly entertaining, fictional dystopia, but as an acute exploration of the emotional dynamics behind cultural, political or religious faith. Like complementary panels of some medieval diptych, it merits study alongside Margaret Atwood’s oddly comparable The Handmaid’s Tale — published in 1985. Though I doubt that any university today would twin the pair.

Amis read, admired and analysed science fiction (or speculative fiction, as the buffs prefer). The Alteration bears witness to his long immersion in its formats and protocols. He creates an alternative 1976 in which, four centuries before, the Reformation in Europe had failed. England never split from Rome. The Tudor Prince Arthur did not die but went on to father a dynasty with the Blessed Catherine of Aragon. A revolt by the villainous Prince Henry (“the Abominable”) led to the “Holy Victory” and the entrenchment of Papal power. Luther himself reconciled with Rome and became pope; so, next in line, did Thomas More.

Amis sidesteps the dangers of the dreary “info-dump” — an endemic sin of science fiction — as he scatters teasing morsels of this alternative reality throughout the story rather than bombarding the reader with tedious expositions. When his American editor objected to this piece-by-piece illumination, Amis insisted in a letter that “one direct and complete tip-off instead of hundreds of indirect and partial tip-offs would impose a disastrously simplistic strategy on the book”. He was right: his approach intrigues, and satisfies. As in our world, England and other European nations have colonised much of the globe: Dahnang Station, south of the Thames, commemorates the English seizure of Indo-China from the French in 1815. But Church always trumps State and no power can rival, or question, the overarching authority of the papacy.

However, two important non-papal polities exist. One is the mighty Muslim empire of the Sultan-Calif in Istanbul, antagonist in an endless cold (and sporadic hot) war with Christendom; recently, Islamic forces have reached Brussels before being driven back. Across the Atlantic, meanwhile, expelled Protestant heretics formed the schismatic state of New England. It covers much of the eastern seaboard, but not the American west or south, which are still in European hands. In this Republic of New England, speculative thought and experimental science can flourish. However, the Native Americans who serve the European elite remain inferiors kept down by a doctrine of “separateness” — apartheid, in our world’s terms.

In Europe, a superstitious horror of electricity and its destructive power has stalled progress on many fronts and limited the population of London to one million (far too many, people grumble). Forests still swathe much of Middlesex. Some breakthroughs have occurred: Amis gleefully devises a steampunk techno-sphere in which a kind of Diesel engine powers fast mechanical carriages for the elite. Trains may move at 21st-century speeds. The “Eternal City Rapid”, for instance, makes the London-Rome run in seven hours as it thunders at 195mph over the Channel Bridge. Luxurious airships float serenely across the Atlantic. Technology, though, counts for less than the marvels of religious art: in the English capital of Coverley (once Cowley, outside Oxford), Wren’s Cathedral-Basilica of St George is a dazzling treasure-house adorned with pious works by devout artists such as William Blake, William Morris and young David Hockney.

For all its rigid hierarchy, Amis’s holy England can beguile with its grace and beauty. Music, art and architecture — the sensory arts sidelined in the Reformation and mourned by English aesthetes ever since — have flourished at world-beating levels of excellence. This England is confidently European, cosmopolitan, not remotely philistine — and utterly unfree. Amis’s glimpses of the musical and visual grandeur cultivated in the place of independent thought have a jewel-like, pre-Raphaelite brilliance. We can almost feel why, lapped in such a plush despotism, many people might opt to swap liberty for loveliness. Clever upholders of the system think that “tyranny alone can let men be safe and serene”.

Amis’s plot turns on the efforts of a fabulously gifted ten-year-old chorister, Hubert Anvil, to escape the “alteration” — ie, castration — that will preserve his God-given soprano voice into maturity. One minor, safe, painless operation (medicine has advanced, at least for the rich) can guarantee a lifetime’s fame and wealth. Art, and faith, demand such a sacrifice from “the best boy singer in living memory”. Or so his elders insist.

Hubert has other ideas. A zigzagging plot sends him in flight from his “alteration” across the landscape of Amis’s unreformed, historically altered country. A totalitarian theocracy, savage but clumsy, directs every aspect of daily life and punishes heresy with brutal swiftness. The mass of the people (like Orwell’s proles in Nineteen Eighty-Four) suffer a lighter yoke so long as they obediently work, pray and drink; they go on foot or horseback while misnamed Diesel “publics” carry their betters. Amis might have had Soviet Russia in mind during the mid-Seventies, but his antennae proved acute: soon, fundamentalist clerics spearheaded Iran’s Islamic Revolution.

From the Tower of London, Lord Stansgate runs the secret police of the Holy Office (one of Amis’s perishable gags: Tony Benn’s title was Viscount Stansgate, but the jibe requires a footnote now). In Rome, the bluff but ruthless Yorkshireman Pope John XXIV (apparently modelled on the novelist John Braine, but with distinct touches of the then prime minister Harold Wilson) governs Christendom with a Machiavellian hand that often grasps a mug of imported bitter ale. Amis piles up the history-switching jokes: Himmler and Beria survive as top Roman bureaucrats; the fiercely secular logician A.J. Ayer becomes Professor of Dogmatic Theology; Jean-Paul Sartre is an orthodox Jesuit monsignor. Rudyard Kipling was “First Citizen” of the heretical RNE, and General Edgar Allan Poe the military genius who defeated the Catholic armies of Louisiana and Mexico.

For all its witty arabesques, Amis’s counterfactual schema has an underlying coherence and consistency. We see how faith-led social control seeks to dominate lives and minds — and why it may falter. In England, “careless, bumptious, over-liberal”, the Pope’s rule has softened a little. A fornicating monk got away with a flogging, for instance, but stupidly repeated the offence — and so “went to the pulley” to be torn limb from limb. As in any totalitarian order, smart, ambitious operators — priests, monks, students — do their duty, hold their tongues, and think forbidden thoughts. “In our world, a man does what he’s told, goes where he’s sent, answers what he’s asked. And, after seeing that, one is free.”

What, though, if a quest for freedom has to break the prudent silence of the sceptical conscience? Hubert’s act of rebellion can hardly be disguised. Abetted by his medical-student brother Anthony and a dissident priest, Father Lyall, who is conducting an affair with Hubert’s mother, the star treble learns about the value of the sexual love the Church will force him to relinquish. In their ecstasy, Hubert hears, lovers may grow “closer to each other than they can ever be to God”. In this regard, Amis sounds like a bloke of his own time. He treats the absence of testicles as irreparable exile from bliss, though the record shows that 18th century celebrity castrati were much sought after as lovers by society ladies. Anthony explains the allure of sexual congress to his little brother by comparing it to Hubert’s favourite treat: chocolate ice-cream. Whereas Amis’s erotic ideal appears to be strictly vanilla.

Hubert’s plans to avoid alteration come to depend on the sympathetic stratagems of the New England ambassador, Cornelius van den Haag. Amis’s portrait of the lone schismatic republic has a fertile ambivalence. On the one hand, the New Englanders do stand for liberty, free enquiry and resistance to autocracy. Yet not only does Amis stress the racial inequality that builds these virtues on a bedrock of subjugated Indian labour (plantation slavery seems not to have taken root in New England territory). He hints that the upright Puritans reserve vicious punishments for social miscreants, and that “alteration” itself may be imposed on sexual transgressors. Here Planet Amis and Planet Atwood, perhaps unexpectedly, start to align.

If the sole free republic has its downsides, then the Pope’s domains — England included — are allowed their charms. With its magnificent basilicas, august ecclesiastical palaces and first-rate music-makers in comely, compact towns surrounded by unspoiled woods and meadows, the country its higher ranks enjoy does resemble the bucolic blueprint of some Anglo-Catholic architect steeped in Ruskin and Morris. But Amis lets us see that the mutilated — “altered” — mind will always be too high a price to pay for this.

Remember, though, that when he wrote the chief real-world models of a totalising system took the form of Soviet or Chinese communism. Although the Bolshoi ballet or Kirov opera might excel, neither regime much appealed on artistic grounds. Re-read The Alteration in the 21st century, and other kinds of gilded prison might suggest themselves. Think, for instance, not of Iran but the orderly, courteous and cultivated spirit of Abu Dhabi. In that emirate (not in brasher, franker Dubai) I have enjoyed the company of gracious, refined servants of the state, with all the subtlety and sophistication of an ancient aesthetic culture at their command. Never mind that Emirati society rests on ruthlessly enforced conformity, obedience to unaccountable power, and an unbridgeable chasm between a favoured elite and a vast servant class. Sink a little into the fragrant pillow of temptation that system offers and the cry for freedom begins to sound like sheer bad manners above all. In The Alteration, Amis conjures a sort of English Catholic equivalent of such a velvet cage — remarkably, since in the Seventies Sheikh Zayed had only just begun to build his fief.

Pluralist liberty, as Amis intuited, must always be rough, messy and discordant. (Young Hubert also excels as a composer, and shocks his tutors with rule-breaking harmonic shifts.) And any beautiful, euphonious society will cast a bloody shadow. Amis hints at secret plague-spreading experiments, masterminded by the Pope, designed to curb population growth. He’s too good a novelist, though, to preach for very long. The Alteration climaxes in a final, startling, twist.

Although dystopian fictions like to warn us against the formulaic reduction of reality, their plots often succumb to an oppressive tidiness. Not so Amis: we leave an older Hubert still lost in a confusing world with “nothing ever measured or settled”. If The Alteration admits the spangly attractions of top-down harmony and unanimity, it underlines the bill that always comes attached. A return visit to its seductive, sinister domain showed me why those gorgeous Gothic Revival churches in my neighbourhood may have such a magnetic allure. And why I’ll never linger in their pews for long.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe