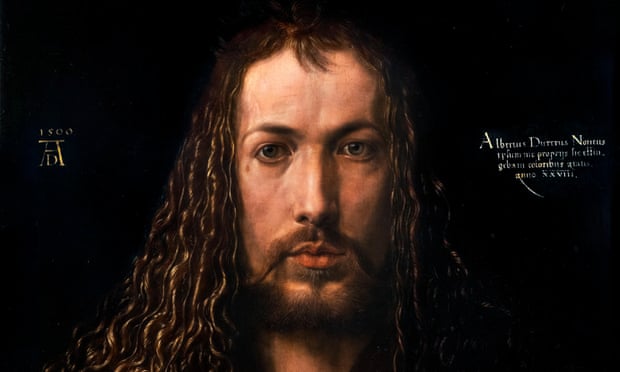

The part-Messiah, part-hipster, all-round superstar self-portrait of 1500, by Albrecht Durer

We’re making a series for radio and we’d like to pick your brains… We don’t have a budget for this project but the exposure will be fantastic… Please come and talk to our students, I’m sure we could cover the fare…

Five years in the freelance galleys have made me familiar with every imaginable formula wielded by salaried cheapskates in order to acquire work, knowledge and ideas for nothing. The digitally-driven age of “free”, in which a vast expansion of corporate and institutional power rests on the exploitation of barely-paid or even unpaid casual labour, has compounded the ancient toxins of Grub Street with a fresh poison of wheedling, entitled hypocrisy.

“Precarity” — a clumsy word for an ungainly state — has always shadowed working life outside the walls of guild, cloister, palace, office, studio or college. And technological upheavals have regularly tilted the balance of the seesaw that links producer and client.

The media evolve, and the money that backs them moves around. What remains constant is a tetchy stand-off between makers and the intermediaries, the patrons, publishers and distributors, who stand between them and their consumers. The mindset of the self-employed artisan or artist — proud, prickly, jealous, at once eager to please and quick to take offence — has endured to jump the centuries between Gutenberg and Google. Visit the National Gallery’s new exhibition devoted to Dürer’s Journeys, for instance, and you meet an artist-entrepreneur who pioneered both the role of the lone creator as hard-bargaining, self-sufficient pro — and found ways to fight back against mean or crooked clients and rivals.

Curated by the gallery’s Dr Susan Foister, Dürer’s Journeys takes as its focus the career-enhancing trips that the Nuremberg-born painter and printmaker took around Germany, over the Alps into northern Italy, and up the Rhine into the Low Countries, at various times between the mid-1490s and 1521. Paintings, drawing, prints and books both by Dürer and his peers present the artist as a shrewd, tough and even cantankerous travelling salesman, avid to collaborate but flintily convinced of his own worth. The National plays with a straight, scholarly bat. So you won’t encounter much of the airy extrapolation that this kind of article routinely indulges. I rather enjoyed the stern rejoinder in one of the catalogue essays that Dürer’s personality “should not perhaps concern art-historical research”. That’s telling me.

But… with my 21st-century, gig-economy spectacles on, it becomes sorely tempting to see Albrecht Dürer, son of a Hungarian goldsmith who had settled in free-trading Nuremberg, as patron saint of the stroppy modern freelance. From Venice to Antwerp, he modelled the novel Renaissance costume of the artist as celebrity. He designed his own logo, cultivated his own brand, and harnessed the new technology of print to spread his fame through engravings and woodcuts to thousands of clients who never saw a painting of his. His sympathy for the humanistic learning of Erasmus (of whom he drew a wonderful portrait in chalk, later engraved) and the reformist theology of Luther partnered a pursuit of professional autonomy, as maker and merchant alike.

Prints and their cross-Europe distribution brought freedom from the capricious arrogance of single patrons: the bishops, dukes and princes who expected you to flatter and fawn for a commission, then paid late and little, if at all. The Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian did grant Dürer a 100-florin pension in 1515, but cannily offloaded its funding onto the Nuremberg city council. The artist struggled for years to get it paid. His triumphant year-long stay in the Low Countries in 1520-21 began with an in-person plea to Maxmilian’s successor Charles V to renew the stipend — but soon morphed into a high-profile business venture, based in cosmopolitan Antwerp.

Dürer saw early that print technology might allow him to make a better living from a hundred merchants than one snooty margrave. His first popular series, the 15-strong Apocalypse woodcuts of 1498, capitalised on the end-times anxieties that gathered as the half-millennium of 1500 drew near. The star illustrator needed a grasp of public hopes and fears, as well as the negotiating nous to strike smart deals. By 1512, after engravings of Christ’s Passion had become a cross-border sensation, the writer of a Description of Germany could state that “merchants across the whole of Europe are buying impressions for their artists”. Dürer attracted not just punters, but copyists too.

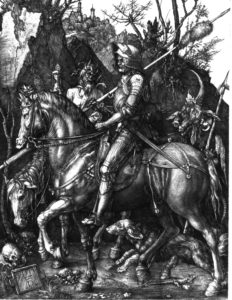

His images – intricate, enigmatic, dream-like – not only sold far and wide. They bedded down into the collective unconscious of his era, and of posterity. It’s no accident that Dürer remains unique among Renaissance masters in that a selection of his graphic works – such as the so-called “Master Engravings” of the 1510s, “Knight, Death and the Devil”, “Melencolia I” and “St Jerome in his Study” – are more familiar than any oil painting he ever did. Save, perhaps, for the cocky Munich self-portrait of 1500; sadly, not in the NG show. In it, the 28-year-old artist gazes out at us with a withering stare from underneath his flowing mane: part-Messiah, part-hipster, all-round superstar.

Mass-produced engravings and woodcuts earned more in the long run than work in traditional media (one set of prints might sell for the same price as a small portrait in oils). They pushed Dürer’s fame into new markets all over Europe. While his mother helped market the product around Nuremberg, his wife Agnes acted as his agent elsewhere in the German lands, especially at the huge Frankfurt fair. Crucially, the print market gave him all the bristling dignity of independence, financial and professional. “Here I am a gentleman,” he wrote from Venice during his Italian sojourn of 1506: “at home I am a parasite”.

While abroad, he drew and painted in return for favours as well as cash. If the Nuremberg master turned up to dinner with a spectacular drawing of the host, and asked for nothing at the time, he would expect the bill to be settled in other ways. After a foray to Brussels, he records tartly that “six people have given me nothing for doing their portraits”. Dürer’s motto might have been “quid pro quo”. Something-for-nothing belonged to the old feudal order he despised. One hard-headed adjective pops up time and again in the revealing journal of his Low Countries travels in 1520-21. Whether a banquet, a robe, a painting, a house, a jewel, if Dürer rates it, it’s köstlich: not pricey or kostspielig as such, but exquisite, lovely, precious, though always with a hint of sheer cash value.

Dürer may have sought to break the chains of royal, noble or ecclesiastical patronage. But, like artists of various kinds today, he did not operate in a pure consumer economy. For reasons of prestige, if not turnover, he needed that imperial pension – which Charles V did finally extend. Likewise, he yearned to secure a splashy, high-end commission from Margaret of Austria, Regent of the Netherlands. She consistently failed to deliver – in fact, she even rejected his gift of a drawing of her father, Maximilian. As his stint in the Low Countries ended, Dürer snarled to his journal that “I have lost out, and quite especially with Lady Margareta, who in return for what I presented to her and gave to her has given me nothing”. Herr Quid-Pro-Quo of Nuremberg kvetches again.

This portrait of the artist as a pennywise hard bargainer, if not a surly old grump, may dismay romantics. It should give comfort to any of his successors, in whatever medium, who would rather ply an honest trade than kiss the hem of patrons – whether the prelates and princes of the 16th century, or the jargon-stuffed arts bureaucrats, conformist dons and trend-crazed plutocrats of today. Dürer’s progress, though, holds another salutary lesson for his freelance heirs. New cultural technologies may carve new pathways between artist and audience. Equally, highwaymen may lurk along them, ready to pounce. More prints meant more forgeries, more imitations, more deceptive pastiche and passing-off.

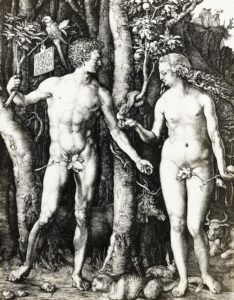

Famously, Dürer devised and applied his “AD” monogram as trademark and signature: not the only Renaissance artist to do so, but the first to make the logo really shout. Just look at where he puts it, too: hanging from the tree on a placard in the Garden of Eden in his “Adam and Eve”; prominently propped up beneath a skull beside the horse’s hooves in “Knight, Death and the Devil”; right under the dedication on a panel next to the great scholar’s hands in the Erasmus engraving; even on the nails driven into Christ’s hands on the cross. How handy, too, for such a tireless self-promoter that he should share initials with the Latin tag – Anno Domini – that marked humanity’s passage through post-incarnation time. Every year could be the year of Albrecht Dürer.

The trouble with logos, though, is that fakers or competitors mimic and purloin them. When it happened to Dürer, he fought back hard. In Venice in 1506, he brought perhaps the first case for copyright infringement, against one Marcantonio Raimondi. A clever print-maker who sailed close to the wind, and once got himself jailed by the Pope as a pornographer. Marcantonio had republished Dürer’s set of prints depicting the Life of the Virgin – AD monogram and all. Dürer sued, but with mixed results. Marcantonio could go on reprinting the engravings, but only as acknowledged copies with the logo removed.

When he published his own edition of the Life of the Virgin in 1511, the ripped-off artist prefaced the pictures with this blood-curdling warning: “Hold! You crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains. Think not rashly to lay your thievish hands upon my works. Beware! Know you not that I have a grant from the most glorious Emperor Maximilian, that not one throughout the imperial dominion shall be allowed to print or sell fictitious imitations of these engravings? Listen! And bear in mind that if you do so, through spite or through covetousness, not only will your goods be confiscated, but your bodies also placed in mortal danger.” Exhilarating, hands-off-my-livelihood rhetoric – even if, like aggrieved content-creators then and now, Dürer overstates the likely penalties in intellectual-property lawsuits with that bit about “your bodies also placed in mortal danger”. If only…

In terms of business acumen and artistic renown, Dürer’s zealous policing of his image and brand paid handsome dividends. His work has never faded from view. When he died in 1528, he left Agnes an estate valued at 6,874 florins – a more than tidy sum. As for those “crafty ones, strangers to work, and pilferers of other men’s brains”, they stayed on the scene.

Non-payment, low payment, late payment and promises of jam tomorrow, or at some unspecified future date, bedevil the freelance life as they did five centuries ago. Across arts and crafts, marketplaces remain as patchy, flawed and skewed as ever. Patronage – now more often corporate than courtly – stands ever-ready to wrap shivering talent in its cosy, stifling embrace. Thieves and tricksters infest cyberspace just as they once skulked around the fairs and print-shops of Renaissance Europe. Revisit Dürer’s work, and you come face to face with a proud innovator who saw how technology and trade conjoined might let his vocation flourish as a profession and a business, too. I’ll be thinking of his grinning skulls the next time someone asks to pick my brains.

Dürer’s Journeys: Travels of a Renaissance Artist continues at the National Gallery, London until 27 February 2022

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe