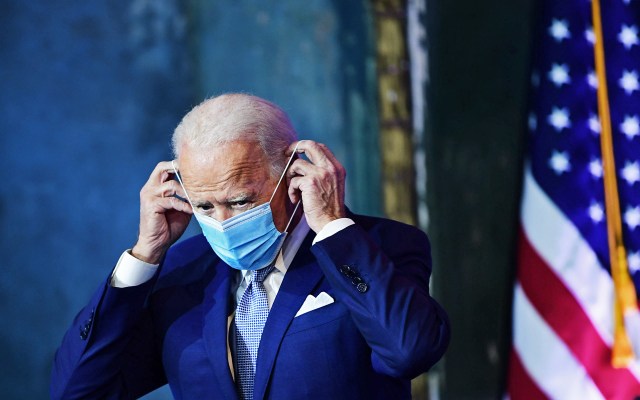

What is America for?(Mark Makela/Getty Images)

A year after Biden’s election, the question of whether anyone really intended to destroy democratic republicanism in the United States is now moot. Forty-six years ago, a headline in New York’s Daily News read “Ford to City: Drop Dead.” Today, the Biden administration and its legion of corporate media and big tech allies communicate the same message to the American people so consistently, and so pointedly, that one can only conclude the humiliation of the electorate is a matter of policy. The administration’s undeniable incompetence, fresh evidence of which is forthcoming every day as it squabbles over vaccine mandates and fails to address multiple crises of supply, inflation, and illegal immigration, both masks and serves its managerial method. Not least because the multiplication of crises furnishes a pretext for ever greater extensions of governmental control.

I am reminded of a trip through Eastern Europe that my wife and I took in 1981. In Yugoslavia one day, we planned to catch a bus in the late morning. The bus and driver were there but the departure time came and went. After an hour we knocked on the station window and the two or three functionaries behind the glass barely glanced up from their hard-boiled eggs and sandwiches. The other passengers remained uniformly inert, neither requesting nor receiving any explanation for what turned into a two-hour delay. It would take years of small humiliations to make a formerly free people this compliant, but that seems to be the goal of the vast coalition of governmental, corporate, academic, cultural, philanthropic, and media powers that has just now fused and hardened, right before our eyes, into an ominous social monster.

There is a common playbook for technocratic control of recalcitrant populations. The Biden administration employs the same siege tactics of declared exigency, deception, division, and intimidation that corporatist progressives used to destroy my former university — Tulsa — two years ago.

After a Left-wing billionaire engineered a hostile takeover of the institution, it was announced that we faced serious crises of finance and accreditation. Faculty were subjected to mandatory training sessions and a blizzard of futile paperwork. The supposedly “data-driven” administration ignored or manipulated information that conflicted with their hidden purposes. While preparing a comprehensive academic review of our department, I learned that the provost had already received the program review committee’s recommendation that our majors in philosophy and religion be eliminated.

The general idea was to overwhelm and exhaust potential opponents of the university’s plan to gut the liberal arts. Surprised by strong pushback, the administration stirred up staff animosity against faculty critics of the restructuring, who were publicly vilified, monitored, and in some cases (including my own) subjected to costly and time-consuming disciplinary actions.

I needn’t belabour the obvious comparisons with the current state of our American union, which has suffered its own hostile takeover. I note rather that the logic of 21st-century technocratic despotism was spelled out long ago in Plato’s Republic. In that dialogue, a class of self-styled experts — the philosopher-kings and their academically-trained ministers — considers its exclusive claim to a science of politics as a title to rule. Contemptuous of what they regard as the ignorant many, they treat their fellow citizens as subjects to be manipulated, and for reasons Matthew Crawford suggested in his essay on the new public health despotism.

They do so first, because persuasion takes time and effort and is less efficient than other available methods for achieving the desired results. In a democratic republic, this is a fundamental corruption of power. Second, because the notion that governance is an applied science or techne encourages the idea that human beings are basically raw materials to be shaped and stamped, like blanks at the Denver mint. Left unchecked, the state’s fundamentally idolatrous desire to coin young souls exclusively in its own image leads to the destruction of the family. The Attorney General’s attempt effectively to criminalise parental veto over public school curricula is a step in this direction. And third, because technocratic elites are inclined to regard the unsophisticated many as cognitively impaired. In the Beautiful City of the Republic, the rulers’ medicinal lies are justified on the ground that one wouldn’t give weapons to madmen. Just so, Dr Fauci’s supposedly noble lies about Covid presuppose that Americans are too sick to be entrusted with the truth.

It is hard to exaggerate the extent to which the therapeutic idiom of bureaucracies has taken hold in United States. (Here again, the University of Tulsa was ahead of the curve, having installed a safe-space affirming psychiatrist as president in 2016.) It is no coincidence that expressions of the manly confidence, candor, and “masculine independence of opinion” that Tocqueville saw as essential to the health of a democratic republic are increasingly likely to be condemned as “toxic”, a term that tries to square the circle by implying that the problem is simultaneously one of social disease and moral depravity. But this is yesterday’s news.

Tyrants have always attacked the political immune system of the people. Fearing spirited assertions of free thought, ancient Greek ones were known to close gymnasiums and ban philosophical discussion. At that time medicine was unsophisticated, and the psychiatric imprisonment of political opponents was not yet possible. Things have not gone so far in our country, but the identification of unorthodox speech and even of silence with violence — itself a symptom of a contagious political madness — serves the same purpose.

Such tactics may be effective in the short term, but progressivist technocratic despotism is disastrous as a long-term political strategy in the United States. It will either be decisively repudiated or do great (and perhaps irreparable) harm to the country. For it betrays a fundamental ignorance not only of what one might call the physics of democratic republicanism, but of the unique nature of the American political experiment.

Plato again illuminates matters. In the Republic, Socrates compares individual souls and political communities to spinning tops. This is a rich and suggestive image. Those short-lived wanderers we played with as children, setting them in motion like little gods, had a lifespan that depended on the rotational impetus imparted by a snap of fingers or string. Encountering irregularities on the hardwood floor, they would wobble and sometimes fall; we cheered when they righted themselves and continued to roam, as they often did. Children instinctively understand the allegorical character of such games.

A top that does not lean in any direction — as happens only at maximum energy — is Plato’s image of the healthy soul and city. Such vital rectitude, which the Romans called religio, was traditionally formed by social ligaments of ancestral custom and habit that constrained the wild impulses of the young and made them straighten up, balancing their characters and aligning them with the ancestors below and the gods above. The ancients understood that moral alignment with traditional and transcendent norms optimises the energy of the human organism in a way that is essential for navigation. Lives tend to drift and fall apart without it.

But punitive doctrinal correctness is no substitute for the basically healthy mores that have long kept the American polity from falling over. Our governing elites fail to understand that courage and moderation are the true and steady foundations of prudent policy. The good kind of political correctness that the Greeks called orthē doxa, upright opinion that furnishes sound premises for political deliberation, is rooted in these virtues and cannot be produced by the moral orthopedics of the propaganda state. The forceful imposition of woke political orthodoxy on the American public can only breed resentment and promote hypocrisy.

While energy is imparted externally to a spinning top, a republic is renewed from within, by the exertions of its citizens. But even well-founded ones eventually fall off kilter. Decline may begin gradually, with minute oscillations, or suddenly, through some external blow, but it always terminates in wild gyrations. Most often, decay results when internal forces move large numbers of citizens, and impede the motions of many others, in ways that throw the whole out of balance.

The chafing humiliations of the Covid police are just part of a surge of social friction that was gestating for years and exploded with the election of President Trump five years ago. Strong political passions, multiplied, amplified, and frequently concentrated on specific targets by corporate media and big tech, have destabilised our essential public and private institutions, virtually all of which, through some demonic Oedipal fatality, now seem intent on repudiating their founding principles and betraying their core missions.

Some of those who, by reason of experience and accumulated wisdom, might still be capable of righting these institutions have been purged; the rest have mostly retired or retreated under fire, withdrawing much good and necessary energy from our common national life. Depleted and uncharacteristically depressed, the American people now spin and shudder along the edge of the abyss. What future awaits us if we forget how to live and work together in amity, and if, emptied of honest debate on matters of pressing concern, the public square echoes with blood curdling war cries?

I have become convinced that a particular deficit of historical memory lies at the root of all our ills. I think there will be no cure for what ails us unless we can recover the answer to one big question: What is America for? What are we about, as a nation? Lincoln taught at Gettysburg that the United States was “conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal”. The twin pillars of our American story are ordered liberty and individual dignity.

Ours is a unique experiment in mature self-governance, testing whether a nation of citizens who are free and equal under the law — and therefore free to make mistakes, to be wrong or right in their own ways and to stand or fall as they will under the hammer of experience — can long endure. This experiment involves considerable risk; as Tocqueville repeatedly reminds us, every one of our political institutions and practices balances goods against evils. But even when faced with the gravest political exigencies, our forefathers reckoned that the rewards of participation in the story of America were too precious to forgo.

This question of risk goes to the heart of the problem Crawford raised. Failure to comply with Covid regulations is presumed to be irrational because it exposes the populace to unnecessary dangers. But risk is always relative to possible outcomes, which today are seen darkly through a glass of psychological and physical safetyism. To take a real example, does the possibility that a student might suffer psychic injury from a book spine justify removing a volume entitled American Negro Poetry from a high school library? But what sort of injury are we talking about? And how does it compare to the possibility that a student will never hear Langston Hughes sing America or speak of rivers, or dream a world “where every man is free”? And above all, who has the right to decide these matters?

Our technocratic mandarins dislike such questions and recoil from the political uncertainties of democratic debate. Whatever its psychological causes, their longing for certainty in practice leads them to insist on it in theory, and so to end debate by any means necessary. This is an engine of comprehensive despotism because it can be satisfied only with the advent of univocal global answers.

The best outcome we could hope for if we continue down this road is what Tocqueville calls “the type of social well-being that can be provided by a very centralised administration to the people who submit to it”. “Travelers tell us,” he writes, “that the Chinese have tranquility without happiness, industry without progress, stability without strength, physical order without public morality.… I imagine that when China opens to Europeans, the latter will find there the most beautiful model of administrative centralization that exists in the universe.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe