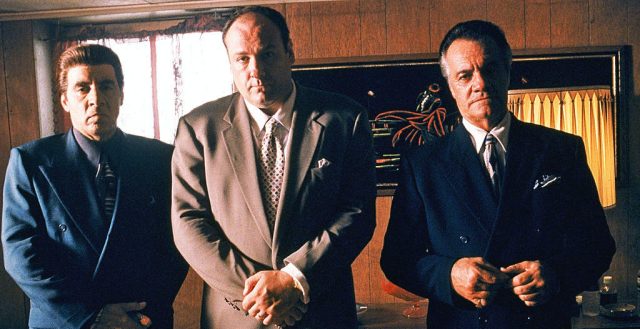

Tony Soprano, looking more like a villain than a victim. (Photo by HBO)

The Sopranos is back. Since lockdown started, viewership jumped by 179%, while one of the most popular podcasts of the Covid era has been “Talking Sopranos”, featuring Michael Imperioli and Steve Schirripa, who played Christopher Moltisanti and Bobby Baccalieri respectively.

This second life of the acclaimed HBO series, which ran from 1999-2007, has been given further energy by the anticipation of The Many Saints of Newark, a prequel film co-written by Sopranos creator David Chase, originally scheduled for last month but postponed until September. The film stars Michael Gandolfini, son of the late Sopranos star James, as the young Tony Soprano.

Widely considered by critics to be one of the greatest television series of all time, a recurring question for fans of The Sopranos has revolved around Tony’s moral character.

“Is Tony Soprano a hero or a villain?” as Michael Imperioli asked in one of the first episodes of the podcast, to which Schirripa replied, “I think he’s both.” The fundamental tension of good and evil contained within the same man captivated audiences throughout the show, and is fundamental to its popularity.

“Tony Soprano,” Schirripa explains, “was the first lead character to be a bad guy who did bad things, yet the audience chose to root for him. He’s a murderer, he’s a drug dealer, he’s a thief, he cheats on his wife, he hits all the sins. Yet, for whatever reason, the audience likes him.”

Throughout the series, people who entered Tony’s orbit met their demise. A classic story plot is a man who makes a wager with the devil, but The Sopranos was the first series to get the audience to sympathise with the devil rather than the man. Throughout the series, Tony kills or orders the murders of a number of people: his best friend, the son of one of his close friends, his cousin, his nephew’s fiancé, and then his protégé nephew. Yet creator David Chase, in collaboration with the immense talent of actor James Gandolfini, got viewers to root for a monster. Tony is clearly not a hero. Instead, the question should be: “Is Tony a villain or a victim?”

Tony was the first mainstream television character to portray what villainy looked like from the point of view of the villain — and what we learned is that no one is the bad guy in their own story. He attempts to be a good father and, to a lesser extent, a good husband — and as reprehensible as Tony was, he was still a better man than his own father. During one of Tony’s sessions with his therapist Dr Melfi, he describes how “the belt was [father’s] favourite child development tool.”

These therapeutic sessions were an ingenious way of giving audience members an insight into the mind of a monster. Initially, Tony visited Dr Melfi because he suffered from panic attacks. Dr Melfi traced the origins of these attacks to a dormant memory: as a child, Tony secretly witnessed his gangster father chop off a guy’s finger for not paying off his gambling debts. Dr Melfi also discovered that when Tony was a child, his mother, Livia, threatened to stab his eye out with a fork. In another flashback scene, Tony’s father suggests to Livia that they relocate to Nevada. Livia loudly replies, within earshot of young Tony, that she would rather smother Tony and his sisters with a pillow than move.

Livia’s random explosions of rage cultivated inner turmoil in Tony. She would lose it over inconsequential mishaps and Tony felt like he had to avoid landmines. “You definitely don’t want to get her started,” he coolly says to Dr Melfi.

The American psychologist Thomas Achenbach made a distinction between “internalising” and “externalising” behaviours for how children cope with stress. Internalising symptoms include depression, social withdrawal and eating disorders; externalising symptoms include drug use, aggression and violence. Tony loved his mother so, as a child, could not carry out externalising behaviours. Instead, he responded to stress at home with internalising behaviours such as panic attacks and depression — a fact acknowledged by Dr Melfi in her explanation that “depression is rage turned inward.”

As an adult, Tony’s unacknowledged, barely contained rage against his mother was portrayed in a key scene early in the series. Today, it might be seen as a little too on-the-nose, but in 1999 its subtlety was novel for television. During the episode, Tony learns that Livia has difficulty with her phone’s answering machine. Later, Tony observes one of his employees having difficulty with an answering machine — just like Livia — and Tony beats him senseless. This is meant to indicate Tony’s true feelings about his mother, feelings he turns against himself or directs to other targets.

Tony’s panic attacks later serve as harbingers of fear or violence on the horizon. For example, in season two, Tony attempts to reintegrate Richie Aprile into his crew after Richie is released from prison. During a particularly heated conversation between them, Tony unconsciously realises that Richie will never be satisfied working for him, and that he will likely have to dispose of Richie. After their conversation, Tony suddenly experiences an attack and collapses.

A key reason Tony Soprano stopped having panic attacks was that he used his sessions with Dr Melfi as an avenue to relieve the stress and guilt he experienced from his violent actions. Therapy allowed him to feel better while continuing to be a violent criminal — but his conscience was never fully unperturbed. Throughout the series, it is implied that Tony is wracked with self-reproach from his criminal activities. There are two ways he can manage this guilt: by changing the actions that give rise to it, or by reinterpreting his actions so that they no longer produce guilt. Throughout the series, Dr Melfi tries, in an unbiased and nonjudgmental way, to guide Tony to change his actions. But often Tony’s sessions merely enabled him to justify himself and continue his criminal acts.

Gradually, thanks to therapy and medication, Tony’s panic attacks subside. But they resurface near the end of season five. Tony is playing golf with New York underboss Johnny Sacrimoni. Johnny says something that leads Tony to subconsciously realise that he has to do something horrible: murder his beloved cousin to prevent a bloody gang war. His body responds with extreme guilt and stress. He collapses.

Yet armed with an understanding of Tony’s origins, the viewer can’t help but feel for him. Of course, Tony is also presented as a relatable — a distant cousin to “likeable” — husband and father, under pressure at work with his employees, trying to fit in with his neighbours and caring for his elderly mother, despite her mistreatment of him. But is this enough to understand why the audience roots for such a reprehensible character?

One reason viewers might excuse Tony Soprano’s misdeeds is because we have sympathy for his plight. In fact, researchers at Harvard Business School and Northwestern University have suggested the existence of a “Virtuous Victim” effect, in which victims are seen as more moral than non-victims who have behaved in exactly the same way. People are inclined to positively evaluate those who have suffered. The audience understands that Tony had a terrible childhood, so when we see him do reprehensible things, such as commit violence or cheat on his wife, we find ways to excuse or downplay it.

More intriguingly, recent research suggests that Dark Triad personality traits — comprising narcissism (entitled self-importance), Machiavellianism (strategic exploitation and duplicity) and psychopathy (callousness and cynicism) — are highly correlated with victim-signalling. In other words, people with dark personalities are more likely to broadcast or feign their victimhood, perhaps to gain sympathy and other rewards, while also getting others to excuse their transgressions.

Does Tony view himself as a victim? He does. In the pilot episode, Tony tells Dr. Melfi that he sees himself as a “sad clown, laughing on the outside and crying on the inside”. He characterises himself again as a “sad clown” in season four, but this time Dr Melfi is sceptical, replying “I’ve never seen it.” She explains that his wife, in a couple’s therapy session, also gave a very different perspective about Tony. Although Tony believes that he responds to inner sadness with outer humour and gregariousness, he in fact expresses his emotions with rage and compulsive eating. Tony views himself one way, but those closest see him as someone completely different.

Sprinkled throughout the show are other indicators that Tony believes he is a victim. In season four, his best friend from high school, Artie Bucco, is in the hospital after a suicide attempt. Tony visits and asks Artie to imagine Tony finding Artie dead, and then asks: “How am I supposed to feel?” He seeks pity from his suicidal friend.

In the following season Christopher, his nephew, accuses him of trying to seduce Adriana La Cerva, Christopher’s fiancé. He tells Tony that he knows Tony was in a car with Adriana alone at night, and that they were going to buy drugs together. Tony becomes enraged and shouts, “So what! I can’t relieve stress every once in a while? I don’t got enough f*****g problems?” Tony’s crew is holding Christopher down, and Tony has a gun in Christopher’s face. Even here, Tony pities himself, and urges Christopher to sympathise with his plight.

Tony is not a sad clown putting on a cheerful face. He wants people to sympathise with him, even as he inflicts violence on them. In a chilling scene, Tony beats up the college dropout son of his late friend Jackie Senior. Tony punches Jackie Junior and tells him: “All I ever did was tell your old man what a good kid you were, and all you do is f******g hurt me.”

By the final season, Tony is even more morally compromised and monstrous than he was at the beginning of the show. But he has fewer panic attacks. Does this mean his treatment was effective? Dr Melfi, in the penultimate episode of the series, terminates therapy with Tony. He responds with dismay: “I think what you’re doing is immoral.”

In The Sociopath Next Door, author and psychologist Martha Stout explained how some people weaponise pity to manipulate others: “More than admiration — more even than fear — pity from good people is carte blanche. When we pity, we are, at least for the moment, defenceless… All in all, I am sure if the devil existed, he would want us to feel very sorry for him.”

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe