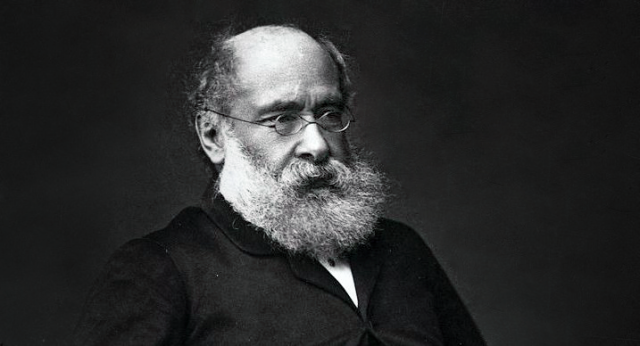

The novelist we need (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

Anthony Trollope — novelist and civil servant — was never a member of parliament. In 1868, when he was 53, he stood as a Liberal for the Yorkshire seat of Beverley. The constituents were notoriously venal. The Tory candidates’ agents bullied and intimidated those whose votes they couldn’t buy. Trollope spent £400 on his campaign (40 times what he got paid for an early novel). He lost, and afterwards said his time on the hustings was “the most wretched fortnight of my manhood”. He never stood again.

It was his country’s loss. Trollope would have made a fine parliamentarian. Unimpressed by precedent or convention, he would have asked the right questions. Far-sighted and sympathetic, he would have supported the right motions. Human foibles amused him. Vice seemed to him pitiful. He would not have been a ranter or a self-righteous denouncer (he detested that type), but rather someone who tried to set things straight. He would have been very good at it. Perhaps, given the chance, he might have made it to the very top. He would have been an eminently well-qualified prime minister.

The sequence of books that he wrote after his disappointment at Beverley, set among the ruling classes and featuring the Palliser family and the ambitious young Irish MP Phineas Finn, are generally known as his ‘political’ novels. But he had already been writing about politics for years. The great novels of his Barchester series, dealing with goings-on among the clergy of an imagined rural diocese, are equally fascinated by influence and its workings, and by the way the would-be powerful manoeuvre themselves into positions of authority.

He was not a polemicist. When Phineas Finn takes up the cause of Irish tenants’ rights Trollope’s other characters act as though jeopardising your career for a matter of principle is eccentric, if not downright irresponsible. Plantagenet Palliser’s interest in currency reform is treated as a joke. But though Trollope didn’t get embroiled in debates about policy, he went deep into politics, and more especially into politicking.

He would have played the Westminster game adroitly. He writes brilliantly about the parasites it attracts: the toadies and the gossips; the schemers who fancy themselves as king-makers; the money-grubbers who make fortunes by promising access, or influence, or favourable press-coverage. He saw how his well-intentioned characters’ good manners and self-delusion made them easy to manipulate, and he was fascinated by the sharper-minded string-pullers who exploited them. I don’t think he would have made a visionary reforming prime minister — he was too alive to the absurdity of human aspiration for that. But I see him presiding at a cabinet meeting — jocular, unruffled, never confrontational — patiently nudging his ministers the way he wants them to go, rather as Mrs Grantly, wife of the Archdeacon of Barchester, defers cheerfully to her irascible husband while he blusters on, sure that he will come round to her way of thinking in the end.

A good proportion of those cabinet ministers — if Trollope could have had his way, and if 19th century law had allowed it — would have been female. Trollope was the child of an ineffectual father and a formidably energetic mother. Thomas Trollope was a not very successful barrister and an even less successful farmer, who never got over the fact that his uncle had failed to leave him a fortune. Fanny Trollope, by contrast, after giving birth to six children, and spending four years living on an experimental commune in America, supported her family by writing over 40 books while travelling around Europe, enjoying the respect of the literary contacts (the Brownings, Dickens) her reputation brought her. In her son Anthony’s fiction Mrs Grantly is one of numerous women, (Lady Glencora Palliser is another) who are subtler-minded and sharper-witted than husbands hide-bound by conventionality and masculine pride. Trollope wasn’t one of those early feminists who believed all women were kindly, peaceable creatures: his Mrs Proudie, the Bishop of Barchester’s sabbatarian bigot of a wife, is a battler. But he certainly knew that men had no monopoly on cleverness.

He was a great communicator. He would have had a warm rapport with the electorate. In his novels he repeatedly drops the authorial mask to address the readers directly. He understood the press. The Warden tells the story of a self-righteous young journalist who takes it upon himself to expose what he sees as the misappropriation of charitable funds. The journalist has got it all wrong, and is sorry for it eventually, but his story allows Trollope to give a penetratingly satirical insider-view of the Victorian media, including a dig at ‘Mr Popular Sentiment’, a thinly disguised caricature of Charles Dickens. Plantagenet Palliser, who is heir to a dukedom, doesn’t bother about comms, but Phineas Finn, making his way, has to repeatedly consider how things will play in the gentlemen’s clubs where reputations are chewed up, and in the scandal-sheets that snap up what the clubs spit out.

Trollope knew the value of money, and the misery of not having enough. His father had sent him to posh schools — Harrow and Winchester — but as a dayboy, which was cheaper. He was bullied and jeered at. Being the poorest boy among a group of rich ones is not the same thing as experiencing real poverty, but it has its own peculiar humiliations. Later, as an ill-paid civil servant, he couldn’t pay his tailor: the bill was bought by a money-lender and Trollope was mortified by duns who barged into his office, nearly losing him his job. His fiction is full of upper-class characters brought low by debt, and of middle-class ones kept down by the exhausting struggle to earn a living. His marriages are always — whatever else they may be — financial arrangements. His great stand-alone novel The Way We Live Now transforms the grey mechanisms of economics into a dazzlingly colourful assemblage of interlocking plots all driven by financial greed or financial need. Had Trollope made it to Downing Street he would never have made the mistake of neglecting the fiscal side of government.

At the age of 19 he started work in the General Post Office, hating the tedium of his clerking duties (clerks were effectively human photocopiers) but seeing no likely escape. He stayed with the post office for 32 years. There are very few novelists who have given proper attention to the daily grind of work — so many, both in Trollope’s time and ours, preferring to focus on love or adventure. He writes mordantly about office hierarchies, about idle, pompous bosses and the frustration of answering to pettifogging bureaucrats. If he’d been running the country he would surely have brought in enlightened employment legislation. He would also have instigated an overhaul of the civil service that eventually lost his loyalty by insultingly passing him over for a promotion.

He was prodigiously industrious. He got up every morning to start writing at 5am, so as to get his daily target of 2,500 words done before he went to work. In his happier times, when he got free of the office and was travelling around Ireland or the west of England as a post office surveyor, he wrote on horseback or in trains. A prime minister’s packed schedule wouldn’t have daunted him. When he finished a novel he didn’t give himself time off. He didn’t even wait until the next day. He reached for a clean page and started the next one there and then.

Writing brought him money (very little to start with, but eventually a good income). He said that that was why he did it, although the exuberance of his fictional inventions suggests he enjoyed creating his novels as much as we love to read them. The autobiography in which he revealed his routine triggered a dip in his reputation. Victorian readers were repelled by Trollope’s self-discipline. Romantically, they wanted their great writers wandering lonely as a cloud, waiting for inspiration to strike. Snobbishly, they couldn’t value work done for pay. One can only deduce those ungrateful readers had large private incomes, and small imaginations.

Trollope’s imagination, by contrast, was capacious. Worldly-wise, phenomenally energetic, an innovator and an acutely perceptive observer of the society around him, he would have run the country with care and consideration. And best of all, he would have done it with kindness. There is a brief passage in The Last Chronicle of Barset that says more about the sadness and precarious dignity of old age than any other piece of writing I know. Mr Harding, a meek-mannered old clergyman whose story has been woven through six novels, is in his daughter’s house. She and her husband are away. Harding is dying. Precisely, without overt pathos, Trollope describes his state of mind. When he wrote that passage Trollope was in his prime. He had a wife and two sons, a full-time administrative job and a popular series of books on the go, but he had the imaginative power to put himself in the mind of a lonely old man facing death. He does it with a degree of empathy that demonstrates what a wise statesman he might have made.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe