Charles Dickens dreams of his characters and his place in the literary canon. Credit: Photo by Mondadori Portfolio via Getty

Charles Dickens permeates London. No statue of him graces the city — in accordance with his wishes — but the characters he created are honoured.

Head east past the Tower and you can drink in the Artful Dodger; travel to Clerkenwell, following the course of the underground River Fleet, and you can take your refreshment in the Betsey Trotwood.

Climb up the stairs on the west side of London Bridge and you’re on Nancy’s Steps, where Nancy, knowing she invites her death in doing so, met young Oliver’s family, to allow the boy to be rescued. Look up in St George the Martyr’s Church on Borough High Street, and Little Dorrit is in the stained-glass window behind the altar.

Off Cornhill in the City, there is no visible homage to Scrooge. But when you have turned down St Michael’s Alley and entered Ball’s Court, you can’t imagine “the covetous old sinner” counting his money anywhere else. Walter Bagehot said that Dickens wrote about London “like a special correspondent for posterity”. But the city in time has also absorbed his artistry into its fabric.

One hundred and fifty years after the author’s death, there is perhaps no place in London where the ghost of the man himself can be felt as strongly as on Borough High Street. Dickens’s life was changed twice over on this street. When he was 12, his father was imprisoned in the Marshalsea prison for debt. Left alone to paint pots in the riverside Blacking Warehouse, he pestered his parents to find him lodgings on Lant Street, which leads off the other side of the throughway so, each morning, he could breakfast with them in the prison.

Dickens’ shame of his knowledge of the Marshalsea, and the innocence he shed there, haunted him for the rest of his life. The place is rarely far from his novels. In Pickwick, it becomes the Fleet prison, in David Copperfield the King’s Bench. When it appears as itself in Little Dorrit, it becomes, at times, the whole of London. “The long bright rays” of the sun across the city are but “bars of the prison of this lower world”. Inside the Marshalsea, there is a freedom from the hurried anxiety the outer city breeds. Those Londoners inside its walls “have got to the bottom” and “can’t fall” any farther.

As he drew Little Dorrit to a close, Dickens went back to the grounds of the fallen Marshalsea, to “stand among the crowding ghosts of many miserable years”. If, by then, he was the most famous commoner in the country, that fame was born in a scene he set on Borough High Street, a little farther north in the White Hart Inn.

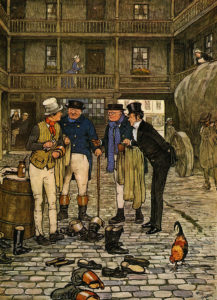

In that coaching inn, he introduced the world to young, street-wise Sam Weller, cleaning boots and sporting an old white hat. What had been the hitherto ramshackle Pickwick Papers, for which Dickens had initially been second-choice hired help to provide text for the illustrator Robert Seymour, became in June 1836, an astonishing publishing sensation. In the months after, people up and down the country bought Sam Weller and Samuel Pickwick paraphernalia and conjured verbal Wellerisms in imitation of Dickens’ cockney, wise-cracker.

Neither were the two ends of Borough High Street quite separate. Sam Weller was part Charles Dickens, with an “extensive and peculiar” knowledge of London, earned on the city’s streets where, neglected by his father, he had learned to ‘shift’ for himself.

Today, Dickens could still walk into the ruins of the Marshalsea. Indeed, turn down Angel Place – Angel Court as Dickens knew it – and you will find your feet not just where the Marshalsea stood as Dickens did in 1857, but on “paving-stones” that tell how Dickens trod the very path.

Look up and your eyes will see large metal mounts with text and pictures from Little Dorrit. Inside what is now a peaceful churchyard garden, where a London Plane tree reaches higher than the last remaining prison wall, the secret Dickens took to his grave is spelled out for all to read. There was so much other history to the Marshalsea. Wat Tyler set fire to the original jail during the Peasants’ Revolt. The playwright Ben Jonson was imprisoned there. But Dickens’s imagination made his family and his characters’ stories the only ones now memorialised.

Lant Street is still a residential street. When Dickens lodged there, it was part of an area known as the Mint, one of the most notorious slums in London with terrible sanitation. In Pickwick, Dickens wrote that a man wishing “to remove himself from temptation; to place himself beyond the possibility of any inducement to look out of the window, we should recommend him by all means to go to Lant Street”. Today, Lant Street offers a swanky wine merchants, and there is private car parking bay on the market for £40,000.

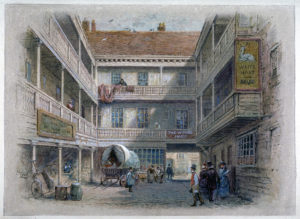

The White Hart Inn no longer stands. But the next-door George Inn does. It is the last galleried coaching inn left in the metropolis, a solitary reminder of Sam Weller and Pickwick’s mode of departure for their adventures.

As Pickwick made Dickens famous, the coaching inns were in decline. Indeed, the very year Pickwick began so did building work on London’s first railway, the London and Greenwich railway, with a terminus at the top of Borough High Street at London Bridge. Looming over the timbered George Inn today are the Shard’s enormous, hard, angular lines. Even if he never saw a building in London much more than a third of the size, Dickens could scarcely have been perplexed by the juxtaposition. As he wrote in the lines just before Sam Weller makes his first appearance, “in the Borough there still remain some half dozen old inns …. which have escaped alike the rage for public improvement, and the encroachment of private speculation.”

Indeed, the George and the Shard are not quite opposites, as in normal circumstances, the National-Trust-owned inn is as much part of the hospitality industry as the other businesses on the street. It is the vanished inns’ narrow alleys and battered arches that have eluded time. On Borough High Street, London is both a mercantile world city, its sky line financed by international capital, and a historical English city still attached to its origins.

A plaque marks where the White Hart Inn once received those who came into London via the Old Dover Road. Its inscription reads that the inn was “immortalised by Shakespeare in Henry VI and Dickens in Pickwick Papers’’. Undoubtedly, the company would have pleased Dickens immensely.

Dickens did not accidentally launch Sam Weller in an inn on Borough High Street. The street has had a good number of other names. It was Wellington Street to Dickens. It was also the Pilgrims’ Way from Southwark. In the Tabard, a little down from the White Hart, Chaucer’s narrator meets a company of pilgrims and decides to let them tell their stories. From the start, Dickens wanted to be remembered as integral to English literary history, and he could not conceive that achievement without place. He met his end at his home on Gads Hill, the place where Shakespeare had Falstaff, whom Dickens re-imagined as Wilkins Micawber, rob pilgrims on their way to Canterbury.

Dickens’ last years were torrid and unhappy. He judged his talent as deficient only against Shakespeare’s, but was well aware his genius was patronised and depreciated by his social betters. He had destroyed his family more surely than his father ever did in the Marshalsea, and, for all his appalling self-righteousness about his cruelty, he, almost certainly, deep-down knew it. As compensation, he craved his audience’s love on arduous readings tours, where he rendered intensely dramatic and emotional performances from his novels, including Nancy’s murder, that worsened his already failing health. Indeed, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that a death-wish hastened him to his end.

On occasion, during those valedictory years, his conscious mind protested a hatred for London. In his last competed novel, Our Mutual Friend, the city is a wasteland beyond collective regeneration.

But he could not keep away. Somewhere, there was still the Georgian city he had walked alone as a child-man during the Marshalsea days. On the last evening of his life, he finished dinner and said he wanted to take the train to London. He then had a fit and fell to the floor. Late the next afternoon, he died, his final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, incomplete.

Edwin Drood is a story written by a man palpably drowning in mortality, one who has come back from London to the Kent of his childhood and, the circle of his life “very nearly traced”, finds that the “beginning and the end were drawing close together”. But London’s reality is part of the circle too. In the penultimate chapter, Dickens made his farewell to the city. The novel’s young characters take a boat up the Thames away from the city to an “everlastingly green garden”. But then came the return, and “all too soon, the great black city cast its shadows on the waters, and its dark bridges spanned them as death spans life” and what Dickens had long known was “unregainable and far away” is lost to them. What is left is “very gritty” London, where, as he might well have hoped, the stones themselves will remember him.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe