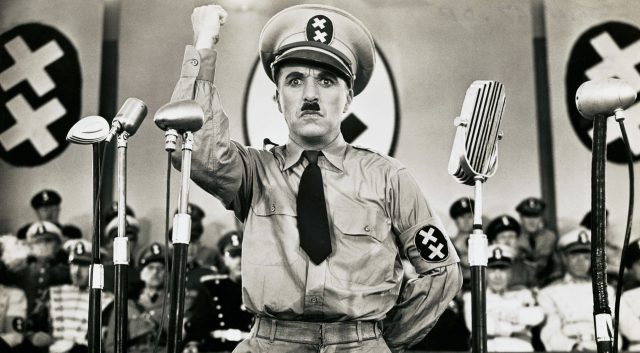

The Nazis banned Chaplin’s films — suspecting his power. Credit: Bettmann / Contributor via Getty Images

Munich, 30 September 1938. The early hours of the morning. But at Number 12, Arcisstrasse, a great cake of white neoclassical marble cut by the Nazi architect Paul Ludwig Troost, the lights are lit. In a room on the first floor, a small crowd has gathered. Men in suits and military uniforms, representing the authorities of Germany, France, Italy and the United Kingdom. Mussolini frowns for the camera. Édouard Daladier, the French premier, slumps glumly in baggy pinstripes. Two more European leaders are present. One is a short twitchy man with a little toothbrush moustache. So is the other.

An official lays out a swathe of papers on the desk. It’s a document that speaks of evacuations, plebiscites and the Sudetenland, and requires four signatures. Mussolini, Daladier and Hitler ink their names. But when Prime Minister Charles Spencer Chaplin is offered a pen, he takes two, sticks them into a pair of bread rolls he has saved from dinner, and uses them, like a little pair of feet, to kick the Munich Agreement on to the carpet.

It’s a dream, of course. An easy one to have if you’ve seen The Great Dictator (1940) in which Charlie Chaplin plays two of his greatest roles — Adenoid Hynkel, the hare-eyed and preposterous dictator of the fictional totalitarian state of Tomania, and his lookalike, a barber from the Jewish ghetto, who puts on an identical uniform to denounce his tyrannical double from the podium at a Nuremberg-style rally. Hitler might have had the same dream. Chaplin’s films were banned in Nazi Germany, where it was widely believed he was Jewish. (“I do not have that honour,” said Chaplin, when journalists asked him if this was true.)

The fantasy of the Little Tramp in Downing Street first entered my thoughts ten years ago on a visit to the Chaplin archive, a secure and temperature-controlled vault beneath Montreux, where the star’s press-books, manuscripts, photographs and letters were then stored on 75 metres of rolling shelving. Working through a stack of newspaper cuttings relating to Chaplin’s trip to Britain in 1931, I was surprised to discover that their emphasis was not on cinema, but politics.

Chaplin’s views on unemployment, economic reform, industrial automation, the banking system and American and European politics were all recorded by the British press. Reynolds’s Newspaper described his ideology as “left-wing Labour”. The Sphere declared him a “radical millionaire”. The Weekly Dispatch, reporting on Chaplin’s meeting with Ramsay MacDonald, then leader of a minority Labour government, wrote it up as a summit between two heads of state, with Chaplin as “the film premier of mirth”. In the photograph, both men looked serious, as if discussing whether Britain should come off the Gold Standard. Perhaps they were. When Chaplin met Albert Einstein a few weeks later, he bent his ear about price controls and quantitative easing. “You’re not a comedian,” said Einstein. “You’re an economist.”

1931 was a cold rough year in British politics. Ramsay MacDonald spent it in government and in crisis. The summer brought the May Report (which urged urgent action on a £120m budget deficit), MacDonald’s resignation and instant return in coalition with the Tories. The October General Election split the Labour Party and left its leader as head of a Conservative-dominated National Government committed to a £70 million reduction in state spending. Labour would not be alone and united in power until 1945.

The newspaper columnist Henry Hamilton Fyfe — a Fabian Socialist and unsuccessful Labour candidate — wondered if Chaplin might be the man to secure the party’s future. He published his thoughts on the day after Oswald Mosley, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, resigned from government to found the New Party, which offered an economic rescue plan on Keynesian principles. (Mosley’s journey to Tomania was, at this point, far from complete.) Fyfe predicted, correctly, that Mosley’s resignation would hand seats to the Tories. “Charlie Chaplin wouldn’t have done that,” he declared. Had the star of City Lights and The Gold Rush been in Mosley’s position, he would have argued the same case, passionately and successfully, from inside Labour. “He would have known that it isn’t enough to have a good story to work with,” wrote Fyfe. “You must be able to catch the fancy of the public. You must grip their interest. You must keep on repeating what you want them to remember. Somehow or other, Mr Charles Spencer Chaplin MP would have managed to get his proposals before the nation in an understandable, attractive form.”

But what proposals? The answer lies in the cuttings. “I think,” said Chaplin, “there is something wrong with our methods of production and systems of credit.” Like Mosley, he was a fan of Keynes. He was also an enthusiast for Major CH Douglas, a former Stockport Grammar School teacher whose Social Credit system envisioned economic regeneration through the payment of a “national dividend” — an early version of Universal Basic Income. (Douglas’s theories about the relationship between unemployment and profit led Chaplin to convert his stock portfolio into liquid capital in 1928, saving him from the effects of the Wall Street Crash.)

Asked by journalists about rising unemployment and stuttering economies, Chaplin proposed “shorter hours for the working man and a minimum wage for both skilled and unskilled labour which will guarantee every man over the age of twenty-one a salary that will enable him to live decently.” The alternative he considered too dangerous to contemplate: “If we continue to view the present conditions as inevitable the whole structure of our civilisation may crumble.” His views were not changed when he travelled on to Berlin, and found Nazi agitators demonstrating outside his hotel. For this, too, he had an answer — one informed by Keynes’s Economic Consequence of the Peace (1919). The issue of $35 billion of a new currency linked to the price of gold, which Germany could use to settle its war debts to the Allies.

Fyfe was not the only person to imagine Chaplin in power. A few days before Mosley’s resignation, Winston Churchill invited the comedian to Chartwell, and, after a robust argument about Lenin and Gandhi, told him to stand for Parliament. Churchill and Chaplin had been friends since 1929, when they met in California by the heated swimming pool of Marion Davies, the actress, producer and mistress of the media mogul William Randolph Hearst. They decided to collaborate on a film about Napoleon. Progress was minimal, but a script was developed by another figure from the British political wilderness — John Strachey, a former Labour MP who had supported Mosley’s ideas for a planned economy, and followed him, briefly, to the New Party. The Napoleon project was never concluded — partly because it evolved, under the influence of the rise of Hitler, into The Great Dictator.

With this in mind, let’s try the full counterfactual. Let’s imagine that when Mosley declines to contest his old seat in the 1931 election, Chaplin takes Hamilton Fyfe’s hint and stands for Labour in Smethwick. (There’s a pleasing resonance to this: when Chaplin died in 1977, his daughter Victoria discovered, locked in a bureau drawer, a letter from a man who claimed that Charlie was not born in London, but “in a caravan [that] belonged the Gypsy Queen, who was my auntie … on the Black Patch in Smethwick.”)

Chaplin’s presence in the Labour party stops it from splitting. He is one of the best-loved figures in the world. His art is founded on an intense personal knowledge of poverty. Working-class voters remember him eating his own boot in The Gold Rush and raising a baby in a garret in The Kid. But he is also admired in Conservative circles and curious about Tory politics. (In our 1931, he went on a boar-hunt with the Duke of Westminster, ballyhooed his friend Nancy Astor at a meeting in Plymouth, wore a disguise to hear the Conservative candidate for Woolwich West speak at Plumstead Baths, and even spent time in the company of Churchill’s ghastly son, Randolph.)

In a country administered by a National Government, he is a unifying figure. The Weekly Dispatch joke about two premiers has become a reality. The Chaplin/MacDonald administration rejects the Means Test and a £13 million cut to the dole, and, converted to Keynesianism, welcomes back Oswald Mosley, preventing the birth of British Fascism.

As for the Continental variety, Chaplin has seen its intolerance and brutality for himself. Nazi publications have been denouncing him for years as a “disgusting Jewish acrobat”. When MacDonald dies in 1937, Chaplin, now the Prime Minister of a Labour-dominated National Government, is ready for Hitler. A draft script for the final speech of The Great Dictator, held in the Chaplin archive, offers a whisper of a possible opening gambit: “Let us right the wrongs done to nations. But as a price let us all disarm — totally — till every instrument of death is destroyed.” It’s not an argument that Hitler would ever have accepted. But Chaplin is also close to Churchill, who has already formed an anti-Fascist network with like-minded figures within British intelligence and the British film business. So the Munich Agreement goes unsigned, and after Chaplin has performed the Dance of the Bread Rolls at Number 12, Arcisstrasse, the Second World War is sooner, swifter and shorter.

At which point we wake up — back in the real world, where The Great Dictator was made, despite the Chamberlain’s government’s active discouragement. (Richard Carr’s 2017 biography of Chaplin unearths this story, which includes a government threat to ban the film’s release in Britain.) Thankfully, its star ignored this pressure, and kept the cameras rolling. Churchill saw the film on 14 December 1940. It was screened for him at Ditchley Park in Oxfordshire, where he stayed on moonlit nights that made Chequers too visible to the Luftwaffe. He laughed heartily, particularly at a scene in which a totalitarian buffet descends into a food fight. He watched Chaplin’s Jewish barber make his speech against tyranny: “Greed has poisoned men’s souls — has barricaded the world with hate — has goose-stepped us into misery and bloodshed.” Then, after sending a secret cable to Washington, the Prime Minister retired to bed.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe