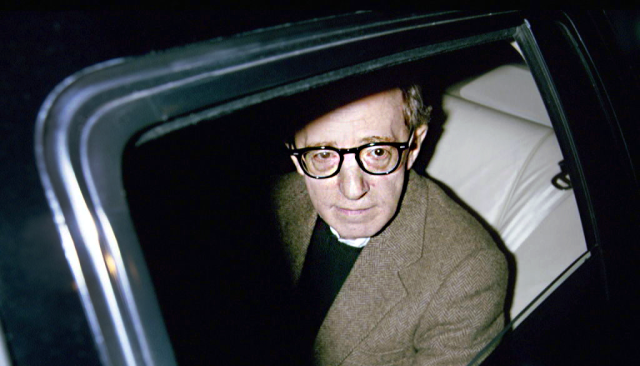

Woody Allen at the courthouse where he answered Farrow’s allegations the first time round. Credit: Rick Maiman/Sygma via Getty Images

There’s a saying, widely credited to Albert Einstein, that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over yet expecting different results. If that’s so, the new HBO documentary series Allen v. Farrow seems like the latest episode in a cyclical drama of collective madness.

The controversy at the centre of Allen v. Farrow is a sort of zombie scandal, a story that keeps lurching back into the limelight, just when you thought it was good and dead. It stems from a now nearly 30-year-old accusation by Dylan Farrow, the adopted daughter of Mia Farrow and Woody Allen, who claims that Allen sexually assaulted her at her mother’s Connecticut summer home in the year 1992. The incident was notable not just for its horrifying details and famous cast, but for its existence within a second, more conventionally sordid celebrity drama. The allegations against Allen came in the midst of a messy split from Farrow, after it was revealed that he’d been having an affair with her 21-year-old adopted daughter, Soon-Yi Previn.

While two separate investigations were launched into Allen’s possible misdeeds, it was the Soon-Yi debacle that dominated both the press coverage and public conversation when the story first hit. Even I, then a 10-year-old kid living in the boonies of rural upstate New York, remember seeing headlines about it in the Arts & Life section of the local newspaper. But by the time the case against Allen was dismissed, thanks in part to a report from the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic of Yale-New Haven Hospital that determined no abuse had occurred, the public consensus was largely in his favour. Not that Allen didn’t have issues — the man had been in therapy since birth and once wrote himself into the role of a sperm, for Pete’s sake — but a paedophile? No, said the gossip hounds and film fanatics. Surely not.

Of course, the thing about public consensus is that it’s changeable — and even malleable, if conditions are favourable and the proper pressure is applied. And while Allen continued making films, and telling stories, his accusers stood by theirs. The assault allegations first resurfaced more than 20 years later, after Allen was honoured with a lifetime achievement award at the 2014 Golden Globes. New York Times writer Nicholas Kristof published a letter from Dylan Farrow in his column at the paper, and questioned Hollywood’s continued support of Allen: “The standard to send someone to prison is guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, but shouldn’t the standard to honour someone be that they are unimpeachably, well, honourable?”

In 2016, Ronan Farrow, Dylan’s brother, renewed the allegations in the pages of the Hollywood Reporter. A year later, Dylan spoke out again, this time in the LA Times. The cultural tides began to turn: actors who’d worked with Allen in the past publicly denounced him; his new film struggled to find an American distributor; and the publication of his memoir was cancelled after employees at Hachette staged a walkout. (The book was eventually released by another publisher.)

And now, three years after the peak of the #MeToo movement, comes a new entry — the “definitive” entry — in the form of Allen v. Farrow. And it’s perfectly attuned not just to a changed political landscape, but a moment of cultural obsession with documentary crime series that make the audience feel like part of the story.

The Farrow camp has asked why the same movement that took down Weinstein didn’t catch Allen under its wheels, a sentiment that’s repeated in the first episode of Allen v. Farrow: “He was able to just run amok while I was growing up,” Dylan Farrow says, her voice full of incredulous frustration. The running amok in question was not criminal or even deviant — Allen is the peculiar #MeToo figure for whom only a single, isolated incident of misconduct is alleged — but it was a life, a fruitful one, and wasn’t that just as bad? If this was a story of good versus evil, Allen’s outcome was the worst sort of twist: here was a villain who not only escaped punishment but thrived in his freedom, so untouchable that not even a movement explicitly founded on the dispensation of justice for long-ago crimes could topple him. As fairytale endings go, this one positively sucked.

But in the era of Serial and Making a Murderer, this apparently glaring miscarriage of justice is the stuff prestige TV is made of — and you, the audience, are part of it. Not just watching but participating, nudging the universe another degree in its incremental path toward justice. Sometimes, the thrill is in correcting the mistakes of overzealous prosecutors, a righteous quest to free the protagonist who was found guilty, yes, but nevertheless seems innocent. But sometimes, and this is even more exciting, you get to catch the bad guy. The audience plays cop, judge, jury, and executioner. The police couldn’t punish the perpetrator, and now it’s up to us; if we all work together, we can make him pay.

Allen v. Farrow is best understood as an attempt to draw us into a narrative that is gripping, outrageous, scandalous, horrifying, and most of all, definitive. This TV series is meant to be the final draft of Woody Allen’s biography: you’ve heard this story before, sure, but this time it’s the official version. The one you remember him by. The one that ensures that when the 85-year-old dies, his obituary headlines describe him not as Woody Allen, Oscar-Winning Director, but as Woody Allen, Alleged Child Molester. (Allen has described it as a “hatchet job”.)

It should come as no surprise that Amy Ziering and Kirby Dick are the team behind the scenes on Allen v. Farrow. These filmmakers often present the “definitive” take on issues like this, which is a nice way of saying that they flatten away the complexity and nuance of a story until what you have is a tale so one-sided, so simple, that it goes down like a communion wafer. Take it on faith. Swallow it whole. Though they bill their work as documentary, the team prides itself on not giving a microphone to whomever it plans to paint as a villain; in a screenshot of a 2013 email that has been circulating online, an associate of Ziering and Dick assures a source that she and her collaborators “do not operate the same way as journalists,” promising “no insensitive questions or need to get the perpetrator’s side.”

This full-throated commitment to incuriosity is a hallmark of Dick and Ziering’s work, which also includes the 2015 film The Hunting Ground, an examination of sexual assault on college campuses that has been broadly criticised for using discredited data and playing fast and loose with the truth. When Ziering was asked by the Boston Globe what people could do to combat the scourge of campus sex crimes, she replied, “You can believe the survivors.”

You can believe — and Ziering is here to help you do it. Her films are something beyond truth: they create the narrative that becomes the official story, drowning every doubt or alternative theory in blazing certainty. The Allen v. Farrow series promises to tell you everything you need to know about the allegations against Woody Allen, yet the information provided over four hour-long episodes points exclusively to his guilt.

What’s in the blurred-out text of the New Haven report from which only a handful of incendiary, out-of-context words have been highlighted? Why are Dylan Farrow’s allegations treated with the utmost respect, while Moses Farrow’s claims of abuse by Mia are dismissed, with a scoff, as fabrication? What was happening in the moments before and after Mia trained a camera on Dylan and asked her to describe where her father touched her? What aren’t we seeing, hearing, being given the chance to consider? Don’t ask. It’s not part of the story.

The documentary is haunted by the spectre of recovered memory — only instead of the victim, it’s the viewing public being asked to confront the truth they’ve been hiding from all these years, to edit their understanding. It’s a tactic that has been effective, even important, for addressing past wrongs within the framework of #MeToo: to think again about that encounter that left you feeling grimy, to revisit, reframe, and ask yourself if maybe it wasn’t your fault after all. For individual women, retelling the story in a different way can be a powerful means of illuminating the grey areas between consent and coercion, or violation versus regret.

But as a means of shaping the public understanding of decades-old allegations, it feels more like propaganda pushed on us by powerful people with tons of cultural clout. Ziering and Kirby’s history of deceptive filmmaking is one thing, but even Ronan Farrow, who appears frequently in Allen v. Farrow as his sister’s staunch defender, has often blurred the line between journalism and activism in his quest to unmask MeToo’s biggest villains. Writing about the work that became Ronan Farrow’s book about Weinstein, Catch and Kill, Ben Smith at the New York Times noted, “[Farrow] delivers narratives that are irresistibly cinematic — with unmistakable heroes and villains — and often omits the complicating facts and inconvenient details that may make them less dramatic.”

In other words, it’s not that Ronan Farrow makes things up. It’s just that he doesn’t like to interrupt the narrative with pesky doubts, quibbles, or caveats. Like this documentary, his work favours a good story over a messy truth.

At the end of the day, Allen v. Farrow is about establishing a narrative more than it’s about changing anyone’s mind. The information it contains is the same information we’ve always had, just repackaged as brave and groundbreaking for the Serial era, in which documentaries are supposed to make a difference — and in a lost year in which the only “safe” activity is sitting at home and watching TV. In this year of no socialising, no sporting events, and very little new content as Hollywood struggles to produce amid pandemic restrictions, here is a chance to feel something. To do something. To be on the right side of history, and be a hero of sorts, instead of just watching them in reruns.

But this is a rerun, too. It’s a story we’ve all heard before, a reboot of a horror show that never should’ve been made into a tabloid spectacle the first time. And no matter how much we might like to think so, tweeting our outraged intent never to watch another Woody Allen film again will not make the world a safer, kinder place for victims of abuse, most of whom will never see their stories told once, let alone over and over. That there’s nobility, even justice, in staying in on Sunday night to watch a premium cable documentary series about a 30-year-old celebrity breakup might be the biggest lie of all.

But we don’t want to think about that. Never mind all the kids who were abused yesterday, who will be abused tomorrow. Tell us the one about the bad little man in the attic again. Maybe this time, it’ll have a happy ending.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe