Dishi Rishi serves the dishy

Cards on the table: I expected Eat Out to Help Out to be an epidemiological disaster. A government subsidy for restaurant meals — an invitation to gather in enclosed, often poorly ventilated spaces to do an activity that physically precludes mask wearing — seemed like a surefire way to send infection rates spiraling. As the scheme kicked off, I was in Aberdeen, which had just been placed under a local lockdown after a coronavirus outbreak linked to 28 bars and restaurants. I feared it was be a sign of things to come as more and more people ate out.

And then: nothing seemed to happen. People surged back into restaurants, industry and Treasury rejoiced, and the infection rate looked like it was under control. Perhaps I had been pessimistic. And yet, as we started to move towards a second wave of the virus, the narrative shifted again. There has been growing concern that actually Eat Out to Help Out did have a negative public health impact. So what does the evidence say?

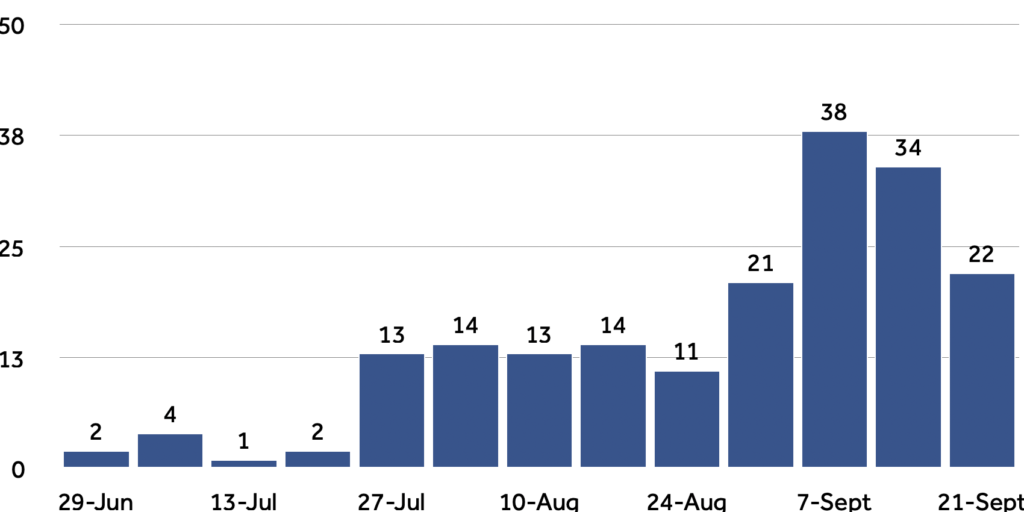

The timing fits, although not perfectly. Confirmed coronavirus cases started to creep up over the month of August, when the scheme was in place, but really accelerated in early September, after it had ended. However, given that use of the discounts increased throughout the month and cases confirmed in early September could have been incubated since late August, it could be evidence of infections being caused by Eat Out to Help Out.

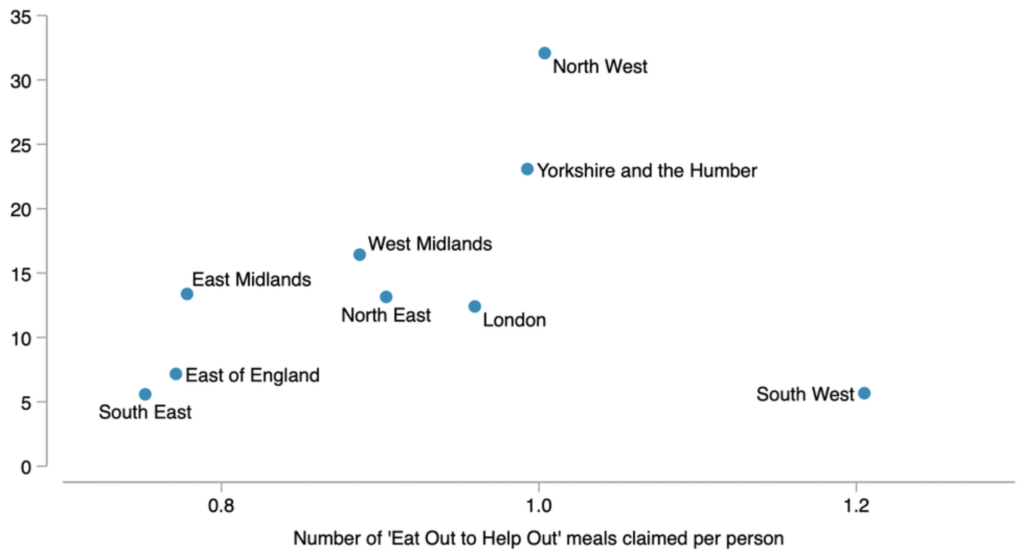

A widely reported piece of analysis by Toby Phillips, a researcher at the University of Oxford showed that at a regional level, there is a “loose correlation” between per head take-up of Eat Out to Help Out meals and new cases of coronavirus in late August.

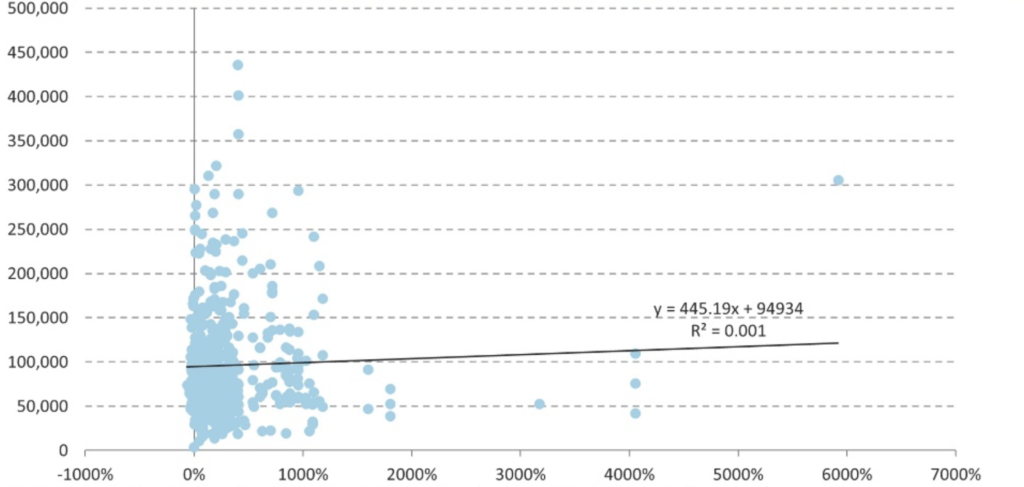

At the same time, the Resolution Foundation’s Cara Pacitti found no association between the number of Eat Out to Help Out meals claimed in particular parliamentary constituencies and the increase in coronavirus cases between mid-July and early September in the associated local authority.

We should be wary of reading too much into such simple correlations — and to their credit both Phillips and Pacitti are careful not to overstate the causal significance. There are any number of confounding factors. There could be reverse causality, if people in areas with higher rates of infection were less likely to use the scheme because restaurants were shut or they felt less safe visiting them. There could be a third variable affecting both infections and meals out claimed: for example urban density or local demographics. It is also possible that the relationship between Eat Out to Help Out and infections is not “dose-response” — where infections rise proportionately to meals claimed. For example, the scheme could merely exacerbate infection rates once case numbers are above a certain level, but have no effect below that.

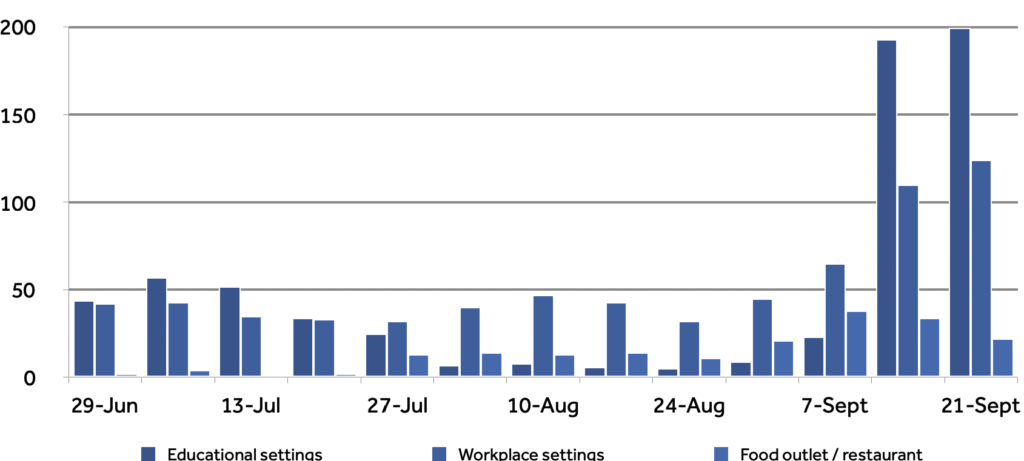

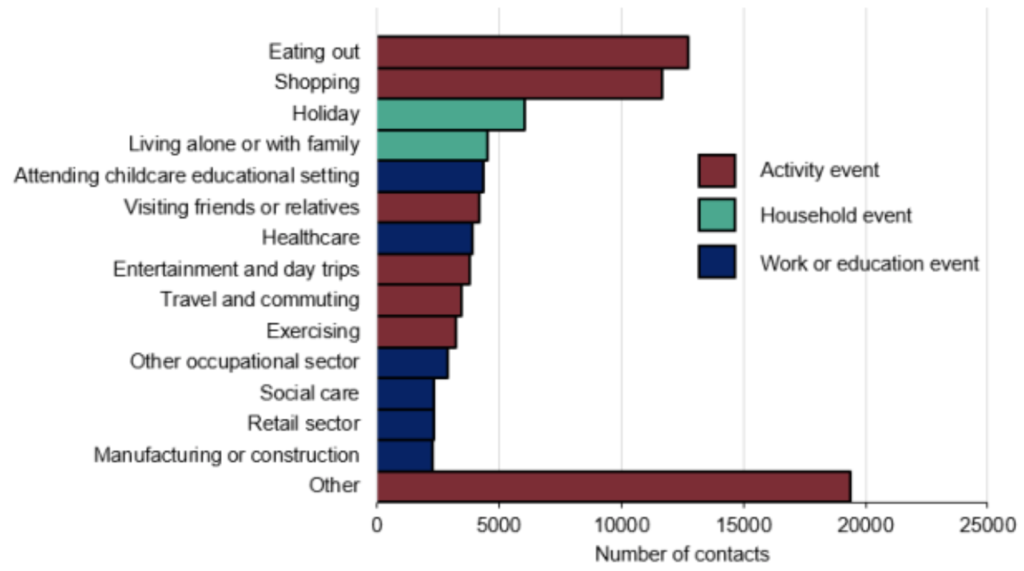

Of course, all eateries were supposed to take the details of diners: contact tracing data ought to be a more reliable source of evidence when it comes to the impact of Eat Out to Help Out on coronavirus infections. However, the limitations of the UK’s Test and Trace programme are well documented, and the compliance of hospitality venues has been patchy. For what it’s worth, the number of suspected outbreaks reported to Public Health England from food outlets and restaurants was flat through most of August, and began to rise in the final week of the month, consistent with a rise in infections with some lag for take-up and testing.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

SubscribeNot the sole cause – overseas summer holidays also made a major contribution. The current second wave sweeping not just through the UK but also Europe has been phylogenetically traced back to norther Spain (which those who think the current virus wave is being imagined will have to admit is a pretty neat trick).