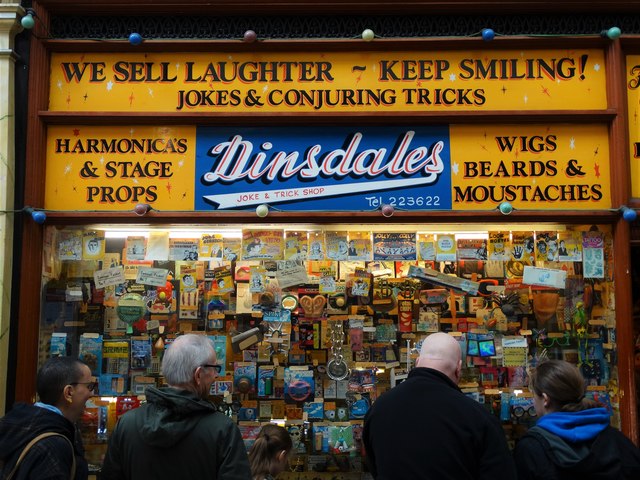

Dinsdales joke shop in Hepworth Arcade. Credit: Neil Theasby via Geograph

In the 1950s, Philip Larkin, the man responsible for the most famous f-word in the English literary corpus (the one about your mum and dad) ran away to Kingston upon Hull because he thought nobody would follow him. This was a city “where only salesmen and relations come”.

It’s not true anymore. Since the beginning of this century, three million visitors have submerged themselves at The Deep, Terry Farrell’s dockside aquarium. 19,000 immigrants have settled in the city, 4,800 from Poland. In 2017, Hull’s status as UK Capital of Culture attracted 5.3 million people to gallery exhibitions, music events and multimedia shows.

Larkin has become one of the attractions. The poet’s sculpted likeness stands in the city, a solid materialisation of Hull’s cultural capital. He welcomes tourists by the barriers at Paragon Station, through which he once passed to take the London train to attend librarians’ conferences and forage on Old Compton Street for Danish porn. Perhaps your mum and dad have seen him. (At the station, I mean, not in Soho.)

This is not an article about how great Hull is. People from Hull don’t write those. Hull, like Liverpool, has its back to England, and thinks of itself as a separate city-state. But we don’t possess that implacable Liverpudlian self-confidence. We do self-doubt and self-pity and shame as well as pride — and we don’t do pride in an uncomplicated way because we’re awkward and bloody-minded when it comes to ourselves as well as others.

Hull doesn’t like being told what to do. In the English Civil War, it refused entry to the king. In the EU referendum, 67.6% voted in favour of Brexit, despite the imminent arrival of a German-owned wind turbine factory — its best economic hope for years. (It remains so.) Hull celebrates its association with abolitionism: a massive statue of William Wilberforce soars above the grey-and-turquoise FE College. Generations of Hull schoolchildren have been sent to the Wilberforce Museum and gazed upon the shackles and manacles of slavery.

When Oswald Mosley visited the city in July 1936, crowds turned up to boo him and some local children cut the wires of his PA system. And yet, in 2009, Hull sent a British National Party candidate to the European Parliament. (Unfortunately, the tweedy neo-Fascist Andrew Brons did not stand for a second term, robbing his constituents of the opportunity to atone for having elected him in the first place.)

Do you want the tour? We could continue the far-Right theme and visit the Ferens Art Gallery to meet Percy Wyndham Lewis – Vorticism’s chief explosives officer, Hitler fanboy and amateur airman. He’s easy to spot — in Mr Wyndham Lewis as ‘Tyro’ (1920) he depicted himself as a reptile-green bandit baring his incisors from an ochreous void. To stand before him is to feel the burning contempt of a Modernist Ubermensch — except Hull has caught him and fixed him, like a prehistoric insect caught in amber.

Less care, unfortunately, has been taken with the friendly face of Modernist Hull — Alan Boyson’s Three Ships, which adorns the side of the British Home Stores building on Jameson Street. It is a landmark of the city and the largest mosaic in the country. Earlier this year, the Council was narrowly prevented from demolishing it — but only for the moment. If they decide it is “unsafe” they might yet pull it down. Hull’s perverse streak showing again.

Hull’s separateness brought Larkin to the Humber and nourished his work. He wasn’t the only one. Hull welcomes artistic migrants. The poet Douglas Dunn was nurtured by the city — it gave him the subject of Terry Street (1969). Basil Kirchin, an audio experimentalist who made soundscapes with birdsong, insect chirrups, the cries of zoo animals and the screams of children, took refuge on the Hessle Road. If you’ve heard his album Worlds Within Worlds (1971), you can indulge your dreams about what he was trying to escape.

Hull is still playing this role. Poets and artists thrive here. It might be because the Humber Estuary is the English landscape’s best shot at true abstraction — three miles of water and an immensity of sky: Larkin’s “unfenced existence”. On the other hand, rents are low, studio space is plentiful, and there’s good coffee on Humber Street.

Some indicators of Hull’s separateness have vanished. The fishing industry, and the lonely, dangerous lives of its seagoing workers. The Ladas that rolled off Russian boats, then rolled over Hull’s wide, uninclined roads. The chunky dial behind the living room curtain that changed channels on the Rediffusion TV — a stormproof radio and television service that arrived through cables under the pavement. (The famous cream-coloured phone boxes are the last memorials of Hull’s status as the Galapagos of British telecommunications.)

Gwenap, which, until it closed in 2009, was thought to be Britain’s oldest sex shop. (At one stage the sign over the door read: “Blow Up Dolls Suit Reformed Terrorists: Make Love Not War.”) The Radburn-style towers of Orchard Park, where travelling people pastured their horses on the traffic islands, and my grandfather surveyed the East Riding from the fourteenth floor of a twenty-storey highrise. (When one tower, Milldane, came down in August 2013, a photograph appeared to show a ghostly figure standing on one of the balconies.)

Walk down Whitefriargate, past the Land of Green Ginger, and you’ll encounter the true spirit of Hull’s oddness. It’s located just inside the Hepworth Arcade, a light-flooded Victorian shopping mall. The window display has barely changed in 50 years. Thick coils of plastic dog turd. Rubber custard creams and bourbon biscuits. Fake bluebottles entombed in Perspex ice cubes. Soap that makes you dirty. Sweets that burn your mouth. Sweets that make you fart. Sun-bleached envelopes bearing line drawings of people from the olden days with nails through their fingers and their eyes rolling in their heads like roulette balls.

Dinsdales joke shop has been in the same family for four generations. Behind the glass-topped counter, there’s always a member of the clan who will supply the history lecture or delve into a musty cardboard box to pull out a tiny tin of 1930s itching powder. (“Worse that a cartload of fleas,” claims the slogan on the lid.)

The shop is small. You can’t ignore your fellow customers — or what might be going on inside their heads. On a recent visit I got talking to a cheerful woman in her sixties who was there to buy exploding cigarettes. These, she explained, would be handed out to anyone who tried to cadge a fag from her on the street. (“That’ll teach ‘em,” she said.) Her haul also contained a couple of dozen little plastic bags, the sort you use to take cash to the bank. Inside each was a crumpled fake tenner. She slipped one into my pocket, but the rest were destined for scattering on the pavements of Hull, where they would act as little punishments for anyone whose spirit might briefly be lifted by the idea of getting something for nothing. The joke shop manager, showing a fine understanding of the psychology of her clients, pulled out a stack of fake winning Irish lottery scratch cards. She had, she said, placed one of these just out of reach of her mother-in-law, with hilarious consequences.

If Hull was on the couch, what would it say? That we had a great industry and we mourn it. We mourn, particularly, the legions of the drowned, upon whom our prosperity depended. But we also breathe a quiet sigh of relief that we are no longer that city whose male population disappeared for weeks on end, came back, drank their wages, beat up their wives and disappeared again. And we’re thankful that nobody is suggesting a post-Brexit return to the stinking feculence of the whaling business.

We’d talk about Hull’s image, too. Hull was the crappest town in the Book of Crap Towns (2003) — whose authors declared that the place “smelt of death” and would, come Judgement Day, be “leased out indefinitely to Satan to provide housing for the Damned”. Jasper Carrott used to joke that restaurants in Hull closed for lunch. When The Economist wrote about Hull, it saw “Britain’s rust belt” where “teenagers in baseball caps and tracksuits wander aimlessly”. (A sight never witnessed, of course, in the prosperous South.)

And we’d talk about Larkin, and his poem This Be the Verse, and its image of misery deepening from generation to generation. The first line is the one everyone quotes: “They fuck you up…” Perhaps, in Hull, we’ve always been a little fucked up. In recent years, the rest of the country seems to have joined us. And I have to say: being fucked up is fine. It’s survivable, anyway. Being fucked, not so much. That’s more serious. The distinction is important. And it would be foolish to pretend, with Covid-19 the subject of our present chapter and a no-deal Brexit the possible matter of the next, that it wasn’t being asked.

Is Britain fucked? Go to Hull. Wander its streets, and you might find out. See its wide impossible sky and the great grey stripe of its river. Gaze upon the pale blues and greens of the Boyson mosaic, the shining contours of Dinsdale’s plastic dog turds, and you may discover the answer. Don’t tell us though. We won’t listen.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe