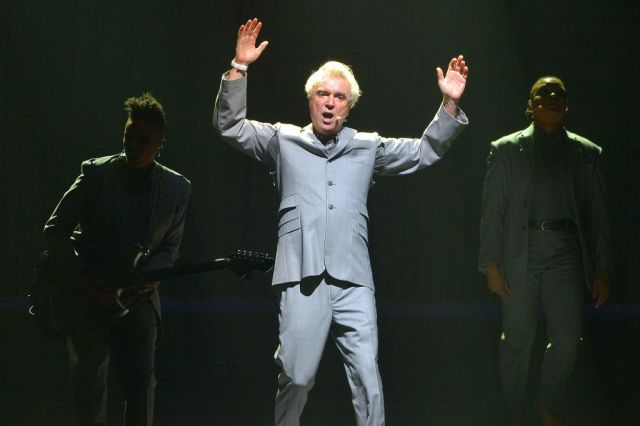

David Byrne, towering frontman for Talking Heads. Credit: Jim Dyson/Getty

Ever since David Byrne’s American Utopia tour came by a couple of years ago, I’ve looked to the former Talking Heads frontman as a model of charm and civility. Lord knows there are plenty of examples of men becoming grumpy, stubborn and cranky as they age. But as “Slippery People” reverberated around the Motorpoint Arena in Cardiff, and Byrne cavorted with his grey-suited, bare-footed, wireless marching band, I saw a useful counter-example.

Here was someone who had reconciled his contradictions; who had found a way to be intellectual but silly, provocative but generous, urbane but cosmic. It doesn’t matter how old you are, I remember thinking, as long as you remain relevant, engaged and open. Most of us could find comfort in that as we age — even if we somehow never got round to making “Fear of Music” in our twenties.

It was a teeny bit jarring, then, to find Talking Heads drummer and co-founder Chris Frantz painting his bandmate of 15 years as an unreconstructed autocrat, a monster, a Machiavellian manipulator. “It’s like he can’t help himself,” Frantz said in an interview last week. Byrne’s brain, he complained, “is wired in such a way that he doesn’t know where he ends and other people begin. He can’t imagine that anyone else would be important.”

Byrne was always seen as difficult in Talking Heads heyday (1977-1991) but Frantz insists that the more genial figure of recent years is an artful construct. “It’s true that his public image has changed,” he said: “But friends of mine assure me that he hasn’t. I think he probably just decided that he could catch more bees with honey.”

The charge sheet is laid out in amusingly petty detail in Frantz’s memoir, Remain in Love — the title referring to Frantz’s long marriage to the Talking Heads bassist Tina Weymouth, rather than any affection towards the band’s frontman. At a student group art show, Byrne moved all of his paintings to the front, reducing everyone else to supporting players. He mocked Frantz for his wealthy parents but turned out to come from a pretty comfortable background himself. He repeatedly neglected to credit his bandmates for bits of song that they wrote. He was bitter and dismissive about Weymouth and Frantz’s side-project Tom Tom Club (“Well, that’s merely commercial music…”).

Why didn’t they play Live Aid? “Oh, that’s right. By 1984, David had decided that Talking Heads, one of the world’s great touring bands, should stop performing live.” And so on. One reviewer has likened Frantz’s book to a photo album “in which someone has cut all the heads off an estranged lover”.

Excruciating stuff. And yet, utterly unsurprising if you have any experience of band politics. Byrne has, to be fair, owned up to the fact that he used to be “controlling and obnoxious”. When presented with vintage Talking Heads footage on Saturday Night Live a couple of years back, he seemed appalled at the memory: “This is a different guy! It is! We change over the years! This is what, 35, 40 years ago?”

But here’s the thing. I’m certain that without the deep polyrhythmic grooviness of the Weymouth/Frantz rhythm section, Talking Heads would have been a worse band. But I’m also certain that if Byrne had been an authentically lovely, generous, urbane person all along, then Talking Heads would not have existed. Or maybe they would… but they would never have moved beyond the art school noodling phase.

And no one would have cared what Frantz thought, because he’d be a retired graphic designer or something like that. If you think of bands as tiny start-up societies, it is fairly clear that one model of government produces more consistent results than any other: autocracy. Even for bands made up of apparently nice, liberal, democratic, progressive individuals. Especially for bands made up of nice, liberal, democratic, progressive individuals.

Hopefully, it’s a benign autocracy. Duke Ellington sought out the most distinctive, personality-filled musicians he could possibly find for his great jazz orchestra and wrote all the parts with individual players (as opposed to individual instruments) in mind. Ellington is often cited by management types for this reason. But tyranny can get results too. Benny Goodman, the “King of Swing”, was by all accounts a complete arsehole. He was seen as progressive back in the 1930s as his big band radically combined black and white musicians, but if you were in the band, this hardly mattered: “He treated everyone like slaves, regardless of race, creed, or national origin,” complained one bassist. If you didn’t play exactly as his vision demanded, you were out.

What we see in both cases is a microcosmic version of the Hobbesian social contract. The state of musical nature is not silence, but “the war of all against all”, i.e. cacophony, everyone playing over each other, the drummer wanting you to try their tune. The only way to ensure peace and harmony is a collective renunciation of individual rights for the greater good. You shut up when it’s not your turn. You whack the cowbell and don’t complain. You leave space. (The more space you leave, in fact, the funkier it usually sounds.) The way you ensure the individual plays their part is via a “visible power to keep them in awe,” i.e. the sovereign, or the artificial construct known as the Leviathan.

The Leviathan is typically assumed to be a king or queen. In a classical orchestra or jazz big band, it’s fairly obvious who has the power: the conductor/bandleader. But in more informal rock-type set-ups, it’s more ambiguous. Singers often assume it’s them. Record companies often assume it’s them. But it can be more than one person — Noel and Liam Gallagher, say — and in some special cases it can be the collective itself. But everyone has to buy into whatever it is or it doesn’t really work.

The more business-savvy bands (U2, REM and Radiohead spring to mind) will usually take a sensible early decision to split credits and royalties equally via financial contracts. (Mick Jagger apparently takes far more pleasure these days from doing the Rolling Stones’ accounting than he does from performing the actual shows.) But the financial contracts are often distinct from the social contract: in Radiohead’s case, it’s still Thom Yorke who supplies the vision and writes the majority of the songs. Mediocre bands tend to fall apart when they run out of ideas and no one cares anymore. But good bands tend to fall apart when the social contract breaks down.

In the case of the Beatles, it was when Paul McCartney began to assume leadership. The same might have happened to the Stones if Brian Jones had survived the 1960s. With Talking Heads, what’s remarkable is that the collective endeavour endured for so long given the evident rancour.

Presumably the Weymouth-Frantz axis was strong enough to absorb what they saw as underhand treatment by Byrne. The collective endeavour was still worth it.

There’s a slightly more hopeful version of this story in Of Mics and Men, the slightly-sugar-coated but still fascinating Wu-Tang Clan documentary — and the stakes are far higher than a bit of art-school sulkiness. Early on, a promoter marvels at the hip-hop group’s improbable line-up of nine extremely idiosyncratic personalities: “I don’t know how in the world you keep all these brothers together!” The documentary is a fascinating insight into how the group’s presiding genius, RZA (né Robert Diggs) managed to do so.

Most of the members had grown up in Park Hill, a prison-like housing project on Staten Island. The details of their upbringings will make you weep: Ghostface Killah looked after two younger siblings with muscular dystrophy as his mother sunk into alcoholism; Method Man sank into depression as the all the other kids in the shelter for battered women where he grew up kept moving on; U-God describes how his two year old son was shot in the kidney after he was used as a human shield by a gang-member.

The shared experiences of violence, poverty, institutionalised racism and near-lynchings from white neighbours formed deep bonds. Meanwhile they developed a collective lore of martial arts references and in-jokes, honing their rap skills to impress each other.

RZA’s challenge was to channel this volatile camaraderie, sell it to an unsuspecting record industry, meanwhile protecting each individual within the group: “Creative control. None of us are gonna be tied down.” He told the other members to donate a year of their life to his plan; they agreed. The group signed as a co-operative, but RZA also insisted that each member sign his own individual deal too — and carefully choreographed the release of side projects so that each would have the chance to shine.

It was a highly idealistic band constitution, a way of reconciling individual autonomy with collective bargaining — and it was executed with a discipline and attention to detail that belied the band’s chaotic image. It was severely challenged by shootings, jail-terms, arguments and the early death of founder-member Ol’ Dirty Bastard. More recently, U-God sued his bandmates for $2.5 million in lost royalties. He complains bitterly about RZA’s control freakery — but he acknowledges that without him, he would be nowhere.

Anyway, the plan just about worked. Wu-Tang Clan remain the most beloved group in hip-hop history. Almost all of the individual members recorded brilliant side-projects. And the eight surviving members are still happy to be in a room together. The collective held out. But it rested on a highly individualistic vision. RZA: now there’s a middle-aged man to admire. He probably deserves a module in business school too.

I’m not sure that there’s any political comfort to take from this quasi-Nietzschean proposition — though the true megalomaniacs, Prince, Kanye, Madonna, Bowie, will usually go it alone. But I think there’s a useful lesson in here for any group endeavour. The best band I ever played in was a ten-piece funk band led by a despotic but extremely talented trumpeter. Rehearsals were tense and frequently humiliating. But we put it up with the hellish regime because in actual performances we were shit hot and that was what we had signed up for. By contrast, I am in an amiable Monday night sort-of-band with some friends, and it will remain a sort-of band forever, as everyone is really nice.

What you soon learn is that talent and even originality aren’t so hard to come by. It’s not so rare to find someone who can play drums OK, or spit a few verses, or even write really amazing songs. What almost never happens is that talent and originality coincide with the sort of ruthless charisma required to sublimate others to your vision. This is why people worship the few musicians who manage to do it. So if you do ever find yourself in the orbit of a Byrne or a RZA, do what the maestro tells you.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe