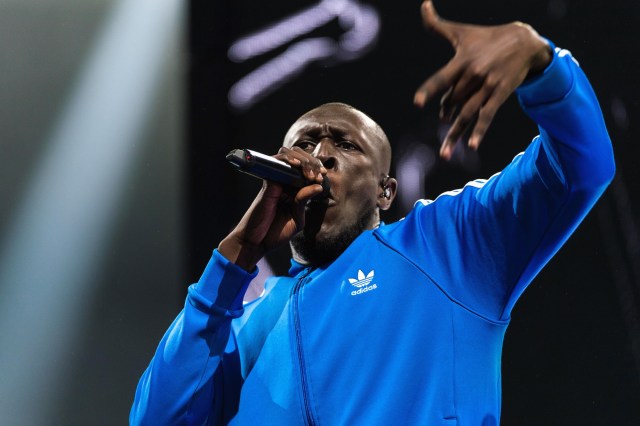

Credit: Ian Gavan/Getty Images

Any half-awake observer of human affairs will have noticed that everyone is being a bit weird at the moment. Not simply weird, but angry, depressed, stressed, jumpy, sensitive, withdrawn, lonely, insecure, constantly checking their phone.

Rappers such as Drake and Stormzy have turned all downbeat and introspective. Your dad is unaccountably furious about what’s happening in student unions. Richard Madeley shouted at Gavin Williamson. The President of America is widely reckoned to suffer from Narcissistic Personality Disorder. I’ve even noticed a downtick in all those social media imprecations to “hustle 24/7” and “keep on crushing it”.

Over on Twitter, it’s Los Angeles author Melissa Broder who best captures the spirit of the age with her @sosadtoday account. Sample tweets: “i feel bad for all of us”; “a positive feeling can f**k you up forever” and “capitalism is making me want to vomit and also buy stuff”. Sad is the new hip.

The idea that we’re living in a new age of anxiety is also borne out by the quantitative data: 8.2 million people in Britain suffer from anxiety; there has been a 68% rise in rates of self-harm among girls aged 13 to 16 since 2011; 58% of teachers believe there is a “mental health crisis” in schools; and universities say they can’t cope.

To some extent, all this reflects a new – and welcome – willingness to acknowledge and address mental health. But it also suggests that there’s a crucial link between what’s happening in our heads and what’s happening in the wider economy. Mental health being such an inward affair, people have tended to blame themselves for their failure rather than, say, the current Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond. The late writer Mark Fisher referred to this as “the privatisation of stress” – the neoliberal tendency to load all of society’s stress onto the individual. But it isn’t until you collate the data – as epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett do in their new book The Inner Level – that the phenomenon begins to assume a definite shape.

“At the heart of progressive politics there has always been an intuition that inequality is divisive and socially corrosive,” they write. “Now we have the internationally comparable data which proves that intuition true.” Their argument, backed up by a formidable amount of graphs, is that the more unequal a society, the more depressed, stressed, anxious, insane and narcissistic its citizens will be, and the less likely to engage in friendly, beneficial community activities.

It’s true across nations rich and poor, true across American states too, and notably true in Britain, the fourth most unequal country in Europe by income. Our children are by some measures the unhappiest in the OECD. One of Wilkinson and Pickett’s main concerns is the “social evaluative threat” – that hard-wired tendency to compare ourselves to others, which is overemphasised in unequal societies (especially ones with Instagram). They describe it as “cancer in the midst of our social life”.

The Inner Level is the follow-up to The Spirit Level (2009), which along with Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st Century (2013), radically altered the conversation about inequality in the post-crash era – even if policy changes have been much slower to follow.

In the first book, the authors showed how educational standards, life expectancy, homicide rates, incarceration rates, heart disease, teenage pregnancy – every problem with a social gradient – are as much as ten times worse in unequal societies as they are in equal societies. What’s more, unequal societies – like the US, Mexico, South Africa and the UK – are worse for everyone in them, not just those at the bottom. It’s sometimes said of parenting that you’re only ever as happy as your unhappiest child. It seems something similar is true of countries.

The Inner Level develops and deepens this theme with a more specific focus on mental health and wellbeing. While the authors stress that it is not a “theory of everything”, the subtitle – How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-being – begs to differ. So too would the terrain covered, from the egalitarian nature of hunter-gatherer societies to the decline of the Ugg boot to the difficulties of genuine friendship between people of different social classes.

The book does raise a few questions. It’s notable that the most equal societies – Scandinavia and Japan – are also rich and relatively monocultural; and that America and the UK, at the opposite end of the “inequality” axis, are rich and culturally diverse. That might suggest that there’s some vexed relationship between inequality and diversity that needs a little more untangling. I also noted, with a minor flush of patriotism, that Britain performs better on volunteering rates than the data would have you expect. And where the authors stray from their number-crunching, they sound less convincing. Do people really manically tidy their house before guests come because they want to hide who they really are? Or perhaps it’s just kind to spare your guests the muesli bowls and dirty underwear.

Nonetheless, the data is compelling – the lines on the graphs all tilt in one direction – and the policy proposals do too. The authors push for full “economic democracy” – employee-owned companies, national wage councils and employee representation on boards – as well as shorter working weeks as remedies within our grasp. Conservative-led governments since 2010 have gradually warmed to the theme of inequality: George Osborne went from protecting the salaries of those earning over £150,000 in his “millionaire’s budget” of 2012, to introducing the National Living Wage in 2015; Theresa May took office vowing to fight Britain’s “burning inequality”.

The gap between the richest and poorest households has diminished since the Great Recession, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies. But there’s still an-inbuilt Conservative blind-spot where it comes to, say, compelling companies like Uber to pay the minimum wage, or welcoming worker representatives onto pay panels, which May promised and then abandoned. Far from discouraging innovation, it turns out more equal societies are also more productive and creative – Sweden cranks out way more patents per head than the US. The Equality Trust has calculated that simply reducing the UK’s inequality levels to the OECD average would save us about £39 billion a year in costs to the NHS and prison service.

The book is timely not simply because the mental health crisis it describes is so palpable, but because the conversations started by the first book have been sidetracked by the shocks of Brexit and Trump, and the rise of populism and identity politics. The collectivist narrative of the “99%” has descended into internecine squabbles: men vs women, TERF vs trans, black vs white, Millennials vs Baby Boomers, etc. The Canadian psychologist Jordan Peterson is reaching huge audiences of young people arguing that what they need is more individual responsibility and less complaining that life is unfair. Stand up straight with your shoulders back!

Peterson likes to talk about the “dominance hierarchy” and argues that the West is doing OK, as it allows the smart and conscientious people to climb to the top. But Wilkinson and Pickett’s graphs show that’s an oversimplification. Being smart and conscientious isn’t enough if you’re born poor. It’s not simply lacking material resources, but the mental effects of being at the bottom of an all-too visible social hierarchy that impact life chances. It means there’s a lot of smart, conscientious people who never get the chance to develop.

Wilkinson and Pickett, moreover, dismiss the idea that we’re wired to assume our rightful place in dominance hierarchies, looking to primatologists and ethnographers to explain why. The literature shows overwhelmingly that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were remarkably egalitarian and cooperative, hunting together, enjoying plenty of leisure time, with no individual among the tribe having privileged access to food or to mating partners – and this is true across cultures and geographies. It wasn’t the dominance hierarchy, contrary to Peterson’s argument, that ensured social harmony, but counter-dominance strategies: the collective efforts of the tribe to hold the strongest in check.

It’s hypothesised that the development of hunting technologies helped this process; once humans invented weapons, the weakest member of the tribe could easily kill the strongest, so the strongest had to ensure that he (or she) ruled by consent. For the system to function and the social organism to evolve, bad leaders had to be overthrown and abuses of power policed. It held until the development of agriculture brought in previously unknown notions of property, ownership, bondage and class, and man was cast out of his Garden of Eden to work the land. Usually someone else’s land.

I say that The Spirit Level was influential. It was a favourite of Nick Clegg’s who – as David Runciman notes in his Talking Politics podcast – was the first mainstream politician to pay serious attention to the nation’s ailing mental health. It was also a book more admired than acted upon in the post-crash era. The financial malefactors largely went unpunished, deemed too big to fail. Incomes at the top decreased a bit, but with wages in the middle stagnant, it wasn’t much solace to learn that some financier is earning £2 million per annum as opposed to £3 million. Particularly so for Millennials priced out of home ownership and paying sky-high rents.

It is little wonder that Millennials, in particular, have flocked to Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party – they make an instinctive connection between “capitalism” and their own ailing mental health. It is they who are dealing with the “privatised stress” of neoliberalism – its “social evaluative” imperative turbo-charged, of course, by smartphones.

Seen from a distance, it begins to look as if we’re in our present turmoil because counter-dominance strategies tired in the wake of the financial crisis have proved abortive. We’re still waiting for the bad ideas to be overthrown. The Inner Level doesn’t make for pretty reading, but it does provide hope that soon enough good ideas will prevail.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe