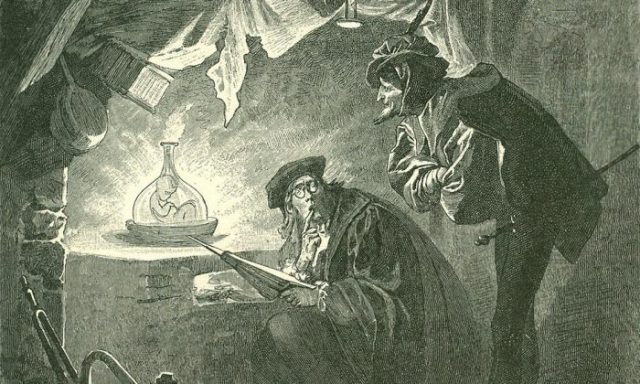

An illustration of a homunculus in a vial by Franz Xaver Simm, 1899.

The removal of the female body from the process of human reproduction, a possibility imagined by generations of science fiction writers – from Mary Shelley, to Aldous Huxley, to Octavia E. Butler – may well be at hand. Or so says Christopher Inglefield, surgeon and founder of the London Transgender Clinic.

He has suggested that transwomen will soon be able to receive a uterine transplant and bear a child. Of course, patients would need to take artificial hormones and birth would have to take place by c-section, but otherwise, the procedure is “essentially identical” to that performed on natal women, since the “the actual ‘plumbing in’ is straightforward”.

It’s an optimistic prediction, to put it mildly. Worldwide, 11 babies have, to date, been born to mothers who have received uterine transplants. They have all been natal females with either a diseased or absent uterus, but an otherwise functioning reproductive system. The transplantation itself is challenging and only a small fraction of uterine transplantation procedures have so far resulted in a live birth.

This, though, starts to look easy when you compare it with the development of another form of reproduction technology: ectogenesis, or gestation outside of the body. Long a subject of interest for science fiction writers, now some researchers are hoping to make it a reality. In 2017, a team in Philadelphia succeeded in bringing a premature lamb to term inside what they called a ‘biobag’, which allows the foetus to continue developing outside of the mother’s body. The lamb was removed by c-section at the equivalent of 23-24 weeks gestation in humans, which is currently the cusp of viability for premature infants.

Some of the media reporting on the biobag, though, has been misleading. “An artificial womb successfully grew baby sheep — and humans could be next” announced one headline, misleadingly. A human embryo can potentially survive in vitro for two weeks following conception, and the biobag might offer 16-17 weeks of artificial gestation at the very end. But that still leaves us with half of the pregnancy untouched.

Perhaps one day these two technologies will meet in the middle, and the human uterus might finally become redundant. But, for now, Adrienne Rich’s 1976 assertion remains true: “All human life on the planet is born of woman. The one unifying, incontrovertible experience shared by all women and men is that months-long period we spent unfolding inside a woman’s body.”

This determination, though, to make the womb — and women — redundant is nothing new. The invention of the incubator in fin de siècle France was also met with an excited response. As the historian Gina Greene has documented, these machines, complete with real babies, were displayed to the general public in exhibitions all over the world and attracted a great deal of media attention. Christened the “artificial mother”, the incubator was welcomed, not only as a means of protecting premature infants from cold and infection, but also as a potential improvement on nature: “perhaps… incubation will be found superior to a mother’s care” speculated one writer in 1904.

A reporter for The New York Times was so giddy with enthusiasm that he failed to check his facts, claiming that a six month old baby had been placed in an incubator for several weeks and had emerged “so strong and healthy that it resembled a child of three years old”, so much so that “it could actually walk”. This rudimentary incubator, it seems, could not only preserve life, it could actually speed up time.

The image of this unnaturally developed baby finds its origins in the medieval era. For scholars back then, the alchemical creation of a homunculus — a miniature, perfectly-formed human being — was a serious academic pursuit. Homunculi recipes were available to would-be creators, for instance in The Book of Cow, which detailed a grisly procedure involving the insertion of human semen into a cow’s womb and the application of various minerals to the resulting newborn, which would then be “at once clothed in human skin”.

These strange recipes, which entirely removed female humans from the equation, relied on an understanding of reproduction expounded by Aristotle, and described by the philosopher Caroline Whitbeck as the “flower pot theory” in which “the woman supplies the container and the earth which nourishes the seed but the seed is solely the man’s”.

There is a common theme here, still present in contemporary media reports on uterine transplantation and ectogenesis. Both scientists and laypeople have historically demonstrated a tendency to both underestimate the complexity of gestation, and overestimate the capacity for medical technology to replace the functions of the female body. In other words, to play down the role of women in reproduction. Hence the persistence of optimistic claims — from Aristotle down through to Christopher Inglefield — that “artificial mothers” of one form or another are just around the corner.

In truth, we still know surprisingly little about the biological processes involved in pregnancy and, as Caroline Criado Perez points out in Invisible Women, it is becoming increasingly clear that the female body is not as well understood as we once assumed. Contrary to what Mr Inglefield claims, female and male bodies are in fact highly dissimilar:

Researchers have found sex differences in every tissue and organ system in the human body, as well as in the ‘prevalence, course and severity’ of the majority of common human diseases… There are still vast medical gender data gaps to be filled in, but the past 20 years have demonstrably proven that women are not just smaller men: male and female bodies differ down to a cellular level.

As Criado Perez goes on to detail, the historic lack of attention paid to women’s unique experiences of disease has often been to their cost. For all this talk of new technologies, there are still a host of bog-standard pregnancy complications that medical science struggles to solve. Treatments for common complaints such as SPD (symphysis pubis dysfunction) and pelvic organ prolapse are often hopelessly inadequate, as the scandal over vaginal mesh implants revealed. And, two centuries on from the development of modern anaesthetics, even the wealthiest Western women are not free from the pain of childbirth. There are just no good options, as a doctor friend advised me recently: choose an elective c-section, and you risk postpartum complications; choose an epidural, and you risk tearing. Many simply choose to tough it out with only gas and air.

Although plummeting maternal mortality rates are a miracle of the modern world, pregnant women in the UK do still die at a rate of about 10 per 100,000 women, with black women suffering a rate roughly five times higher than white women for reasons that are not well understood. Only last week, 24-year-old YouTube star Nicole Thea died in her eighth month of pregnancy, along with her unborn son Reign. It is thought Thea died of a heart attack, something which, though rare, is still the leading cause of death during pregnancy.

There are still so many things we don’t know about childbearing, and still so much pain and danger that can’t be alleviated — sometimes for want of healthcare resources, and sometimes for want of scientific knowledge. There is a thrill to be had in pushing the boundaries of human experience, and this is no doubt attractive to those hoping to create startlingly new reproduction technologies.

I don’t doubt that it could one day be possible to grow a foetus inside the body of a natal male, or indeed outside of the human body altogether. But it’s still a long way off. And in the meantime, it’s hard to see the justification for devoting finite medical resources to the development of these speculative, artificial mothers, when real mothers are suffering in the here and now.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe