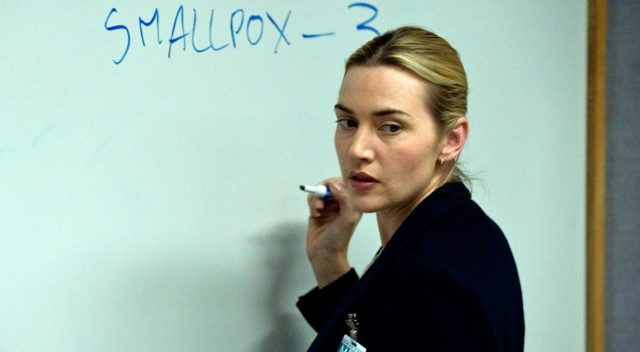

Kate Winslet explains the Rº of various diseases in the film ‘Contagion’

At the end of last week, you may have seen some rather scary news: the R value, the average number of people infected by each person who has Covid-19, had gone back up.

Professor John Edmunds of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine appeared before the Science and Technology Committee of the House of Commons and said as much. The R value was now between 0.6 and 1, he thought, but “if you’d asked me two weeks ago I’d have given lower numbers, about 0.6 or 0.7, maybe up to 0.8.” It got quite a lot of attention.

But I want to suggest (as in fact Edmunds himself did) that this isn’t the bad news people seem to think; in fact it’s a product of our success, rather than of our failure. Here’s why.

There’s an interesting statistical anomaly called Simpson’s paradox. It is that you can find a trend going one way in lots of individual datasets, but that when you combine those datasets, it can make the trend look like it’s going the other way.

That sounds quite dry, so let me use a famous example. In the autumn of 1973, 8,442 men and 4,321 women applied to graduate school at UC Berkeley. Of those, 44% of the men were admitted, compared with just 35% of the women.

But this is not the clear-cut example of sex bias that it seems. In most of the departments of the university, female applicants were more likely than male applicants to be admitted. In the most popular, 82% of women were admitted compared to just 62% of men; in the second most popular, 68% of women compared to 65% of men. Overall, there was a “small but statistically significant bias in favour of women”.

What’s going on? Well: men and women were applying for different departments. For instance, of the 933 applicants for the most popular department — let’s call it A — just 108 were women, but of the 714 applicants for the sixth most popular department (call it B), 341 were women.

Let’s take a look at just those two departments. Women were more likely to be admitted to both. But, crucially, the two departments had hugely different rates of acceptance: in Department A, 82% of female applicants and 62% of male ones were accepted; in Department B, 7% and 6%.

So of the 108 women applying to Department A, 89 of them were admitted (82%), while of the 825 men applying, 511 got in (62%). Meanwhile, of the 341 who applied to Department B, just 24 (7%) were admitted; for men, it was 22 out of 373 (6%).

You see what’s going on here? In both departments, women were more likely to be accepted. But added together, it’s a different story. Of 449 women who applied to the two departments, just 111 were accepted: 25%. Whereas of the 1,199 men who applied to the two, 533 got in: 44%.

So, to repeat: even though any individual woman applying to either department had a higher chance of being admitted, on average fewer women were admitted because they tended to apply to more competitive departments.

This doesn’t mean that we’ve once-and-forever ruled out any form of sex bias — it might be, for instance, that there is a lack of investment in the popular but female-dominated classes — but it does show that the simple, top-line, aggregated numbers can mislead. When divided up into smaller groups, they can tell a very different story.

Simpson’s paradox is a specific case of a wider class of problem known as the “ecological fallacy”, which says that you can’t always draw conclusions about individuals by looking at group data. A topical example: local authorities with above-average numbers of over-65s actually have a lower rate of death from Covid-19 than those with below-average numbers. But we know that older people are individually at greater risk. What’s going on seems to be that younger areas tend also to be denser, poorer, and more ethnically diverse, all of which drive risk up.

The apparent rise of the R value seems to be something like that. According to Edmunds, the rise is not because lockdown isn’t working (“it’s not that people are going about and mixing more”), but that it is working. There are, he says, separate epidemics in the community, and in care homes and hospitals.

“We had a very wide-scale community epidemic,” he told the committee, “and when we measured the R it was primarily the community epidemic. But that’s been brought down: the lockdown has worked, breaking chains of transmission in the community … now if you measure the R it’s being dominated by care homes and hospitals.”

Let’s imagine that we had two epidemics, of equal size, one in the community and one in care homes. Say 1,000 people are infected in each, and in the community each person on average infects two people, while in the care homes on average each person infects three. The total R is 2.5[1].

But now imagine you lock down and reduce both the R and the number of people infected, but by more in the community than in the care homes. Say that now there are 100 people infected in the community, and they each pass it on to an average of one person; and there are 900 people infected in the care homes, and they pass it on to an average of 2.8 people.

Now your average R is 2.62[2]; it’s gone up! But — just as with the Berkeley graduate students above — when you divide up the data into its constituent parts, it’s actually gone down in each category.

I don’t know the numbers, but according to Edmunds something like this has gone on in the real world. The collapse in the number of people with and passing on the disease in the community means that now the epidemic in care homes is a much greater share of the average. And that means, even though the R in care homes hasn’t gone up, the average R in total has, because the average in care homes was higher to start with.

To be clear: this doesn’t mean that everything is fine, or that we’ve won, or anything. “The thing that worries me is that it might be the overall R that matters,” says Kevin McConway, an emeritus professor of statistics at the Open University, who helped me understand these numbers. It’s not that the epidemics in the community and in care homes and hospitals are truly separate, islands cut off from each other — they’re interlinked, so if the disease spreads in care homes it can reinfect those of us outside it.

Edmunds said as much to the Science and Technology Committee: “Strictly speaking you have one R: there’s one epidemic and linked sub-epidemics; the epidemic in hospitals is not completely separate from the one in the community.” But to understand how it works, you need to look in this more granular fashion: the overall R is not much use on its own.

And while it doesn’t mean that we’ve won, it certainly shouldn’t be taken to mean that the British population has been lax in its approach to lockdown. Compliance has been very high, much higher than modellers anticipated.

But it does show that simple numbers can hide more complex stories. They feed, for instance, into modelling. One simple model is the SIR (susceptible, infected, recovered) model, where you assume everyone just interacts at random, mixing uniformly like molecules in a gas; but if the epidemics in care homes and the community behave very differently, then those models might give out very misleading numbers.

That’s why models such as the Imperial one try to simulate human behaviour to some degree; the extent to which it got that right is far from clear, but it was at least trying. Some more simple models that went around the internet did not. McConway, a statistician not a modeller, is profoundly wary of those: “I know enough [about modelling] to say I wouldn’t touch it because I’m not an expert; I see people getting it wrong in ways that I can recognise, whereas I’d get it wrong in ways I don’t recognise.” These subtle misunderstandings can drive major errors.

We’ve seen examples of this throughout the crisis. Early on, people (Donald Trump, notably) paid an awful lot of attention to the case numbers; but the case numbers didn’t really tell us how many people had the disease, just how many of them had been tested. And people have tried to place countries in a league table of death rates, but that’s not particularly informative either (although that’s not to say comparisons are entirely useless). Trying to boil down this messy, complicated situation to single numbers and saying whether they’re good or bad is rarely a good idea.

The really key thing, which I keep coming back to, is just how much uncertainty there is. “Modelling is bloody hard,” says McConway. “Prediction is bloody hard. The map is not the territory. We’ll know what’s happened when it’s happened.” Even something as apparently simple as the R value has to be treated with immense caution.

[1] ((1,000*2)+(1,000*3))/2000=2.5

[2] ((100*1)+(900*2.8))/1000=2.62

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe