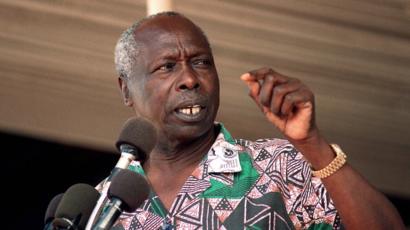

Daniel arap Moi, the schoolteacher who became a dictator. Credit: Getty/Images

The former Kenyan president, Daniel arap Moi, died earlier this week at the age of 95. Throughout his 24 years in power, between 1978 and 2002, he created a long and complicated legacy for himself and for his country. But he is best remembered for cynically and at times recklessly manipulating ethnic and religious tensions for nefarious ends.

Moi was for many years an unassuming man. Unlike Kenya’s first president, Jomo Kenyatta, and his vice president, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, he was neither an outspoken firebrand nor part of a large ethnic group; he was a successful but not particularly notable politician, a former schoolteacher, church elder and teetotaler from a small ethnic group. Odinga quit in 1966 and Moi was installed as VP; he posed no threat of upstaging his boss.

When Kenyatta died in 1978, Moi was nearly pushed aside for the presidency; only an intervention by the country’s attorney-general prevented Kenyatta’s clique from circumventing the country’s constitution to place one of their own in power. Moi was challenged again in 1982, when members of the Kenyan Air Force mutinied.

The coup was unsuccessful, but it inspired in Moi a permanent sense of threat. His party, Kenya Africa National Union (KANU) had already banned opposition and made the country an official one-party state; after the coup, Moi began targeting all sources of opposition. Political activism by students, professional associations and trade unions was banned. Kenya’s powerful ethnic associations, which wielded significant economic and social power on behalf of prominent members of large ethnic groups, were outlawed. Dissenters were arrested and detained for months, many subjected to beatings and torture in the basement of Nyayo House, the towering skyscraper opened by the Moi government that dominated the Nairobi skyline. The political functionary had become a ruthless dictator.

But it wasn’t enough for Moi to suppress sources of dissent or opposition. He needed to forge his own independent base. And so he cobbled together a political identity based on ethnicity and faith.

His ethnic group, the Kalenjin, were famous for producing world champion runners but otherwise relatively obscure. In fact, they were barely recognised as a group — Kenya’s Kalenjin-speaking clans were only listed on the country’s census as a single group after Moi was in office. Moi promoted the prominence of his group, placing a disproportionate number of fellow Kalenjin in prominent positions throughout his government. He supplemented his coalition by recruiting politicians from other obscure communities among Kenya’s 42 ethnic groups, thus guaranteeing that his subordinates lacked independent bases of power and would therefore be loyal to the president who kept them in power.

But it was also as a man of faith that Moi found his political persona. Throughout the 1980s and 90s, just as conservatives in the United States were empowering Evangelicals as a political force, Moi was performing a similar task in his own country. Kenya is a deeply religious country, and its various Christian denominations have long been major forces in politics and society. In the days of colonialism, the British Anglican and Presbyterian churches worked hand-in-hand with colonial administrators to govern the local population. During the independence struggle, African independent churches broke away from missionary-founded denominations and sometimes even supported armed freedom fighters during the infamous Mau Mau rebellion. After independence, Kenyatta (not a religious man himself) tapped into the resources of the Catholic and mainline Protestant churches to assist the new government in the task of statebuilding.

For Moi, however, religious groups were not seen as useful partners for providing education or healthcare, but as vehicles for legitimising his own rule. President Moi could be found sitting in the front pews of an African Inland Church (of which he was an elder) every Sunday morning. Clergy from this church and from other Evangelical denominations were given places of honour at official state functions. Kenyan politicians had long used church fundraisers — “harambees,” or “coming together” in Swahili — as a way of handing out money and favours to ingratiate themselves to various communities; Moi took this practice to new levels, dolling out unprecedented amounts of money at these community events.

Pundits in the United States wondering how American Evangelicals might continue to support Donald Trump could learn something from arap Moi’s example. By giving a place of privilege and honor to Evangelicals in Kenya, Moi in turn gained the unfailing loyalty of many members of the community, who had previously lacked the prominence of the older Catholic and Protestant denominations. When I visited the head office of the African Inland Church years after Moi’s retirement, his picture still hung prominently on the walls.

As the winds of democracy began to sweep across Africa in the 1990s, Moi’s Evangelical backers used scripture to preach obedience and submission to state authority, condemning pro-democracy advocates as troublemakers and apostates. Romans 13, “Let everyone be subject to the governing authorities, for there is no authority except that which God has established,” was a favourite verse for Moi’s church backers to cite; scripture about speaking truth to power, less so.

Moi’s supporters also turned a blind eye to the tactics he used, even against dissenting religious leaders. As the Evangelicals doubled down in their support for Moi, the country’s Catholic and mainline Protestant churches became increasingly critical of his autocratic rule, with sometimes dire results. One particular thorn in Moi’s side was the Anglican Bishop Alexander Muge. In 1990, one of Moi’s ministers threatened that Bishop Muge “might not leave alive” if the bishop followed through on a planned visit to the minister’s constituency; three days later, Bishop Muge was killed during the trip in a traffic accident that many believed to have actually been a hit ordered by President Moi himself. His Evangelical supporters argued that it was the clergy who dared oppose the president who were at fault.

By the early 1990s, local activism and international pressure forced Moi to drop one-party rule and open up the country to elections, but Moi shrewdly manipulated identity politics to get his way. Government agents stired up old land disputes, which erupted into ethnic violence, to displace voters in opposition areas and thus prevent them from casting ballots against him. All the while, Moi continued to tout his religious bona fides and hand out ever larger sums of cash at fundraisers. Many Evangelical leaders remained loyal; one preached a sermon in which he declared, “in heaven it is like Kenya has been for many years. There is only one party — and God never makes a mistake.”

Simultaneously, Moi manipulated international opinion in his favour. For his Western audience, what Moi did remained less important than what he was not. During the Cold War, Moi presented himself as a staunch anti-Communist, meeting multiple times with Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. Even as Kenya’s economy crumbled from corruption and mismanagement, his relationships with the West brought in aid and support that kept the country afloat. Later, after al-Qaeda killed over 200 people by bombing the American embassy in Nairobi in 1998, Moi allied himself with the US in the fight against the group and against terrorism — fully three years before 9/11 formally sparked the American-led War on Terror.

Moi’s influence endured after he left office. KANU was defeated in the 2002 election, but Moi remained a revered figure. He was never called into account for the brutality of his rule, and doggedly defended his policies as having been in the best interests of the country. He would occasionally chime in on pressing issues, but largely left politics to a younger generation.

Nevertheless, the practice of electorally-motivated violence Moi unleashed during his presidency continued to affect Kenyan politics until a disputed 2007 election (the first in which Moi’s candidacy or endorsement were no longer issues) led to massive ethnically-fuelled violence, which left the country burning and over 1,000 Kenyans dead.

Even though these clashes led to various political reforms (rarely have I seen a public as interested in the fine points of constitutional law than I witnessed in the streets of Nairobi in 2010 ahead of a vote to approve the country’s new constitution), few people were held accountable for the violence. Indeed, two prominent politicians implicated in organizing the violence from opposite sides of the conflict — Uhuru Kenyatta, the founding president’s son and a former political protégé of Moi, and William Ruto, who has assumed the mantle as standard-bearer of the Kalenjin ethnic group — put aside their differences and ran a joint ticket; they are now president and vice-president of the country. Kenya’s religious leaders, meanwhile, found themselves ineffective at stopping the violence that broke out in 2007, and many of the country’s top clergy have subsequently positioned themselves in opposition to everything from constitutional reform to LGBT rights to public vaccination campaigns.

Much has been written over the past three years about how Donald Trump represents not a backlash against identity politics but a perversion of it: he mobilised a minority of Americans along ethnic and religious lines to successfully take the reins of power. But Trump was far from the first politician to ignite a dormant ethnically-based politics among his supporters or make a Faustian deal with conservative Evangelical Christians, who support him and turn a blind eye to abuses of power. Daniel arap Moi did it earlier and for much longer.

Creating national unity was always an uphill battle in Kenya: arbitrarily jamming together dozens of linguistic groups into a single colony all but ensured divided loyalties within Kenya’s borders. But Moi could have been an advocate, giving voice to previously marginalised ethnic and religious groups within Kenya in a way that respected the plurality that existed within the country. Instead, he opted for a tyranny of the minority, and in the process he seeded deep divisions in Kenya that are taking decades to fully heal.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe