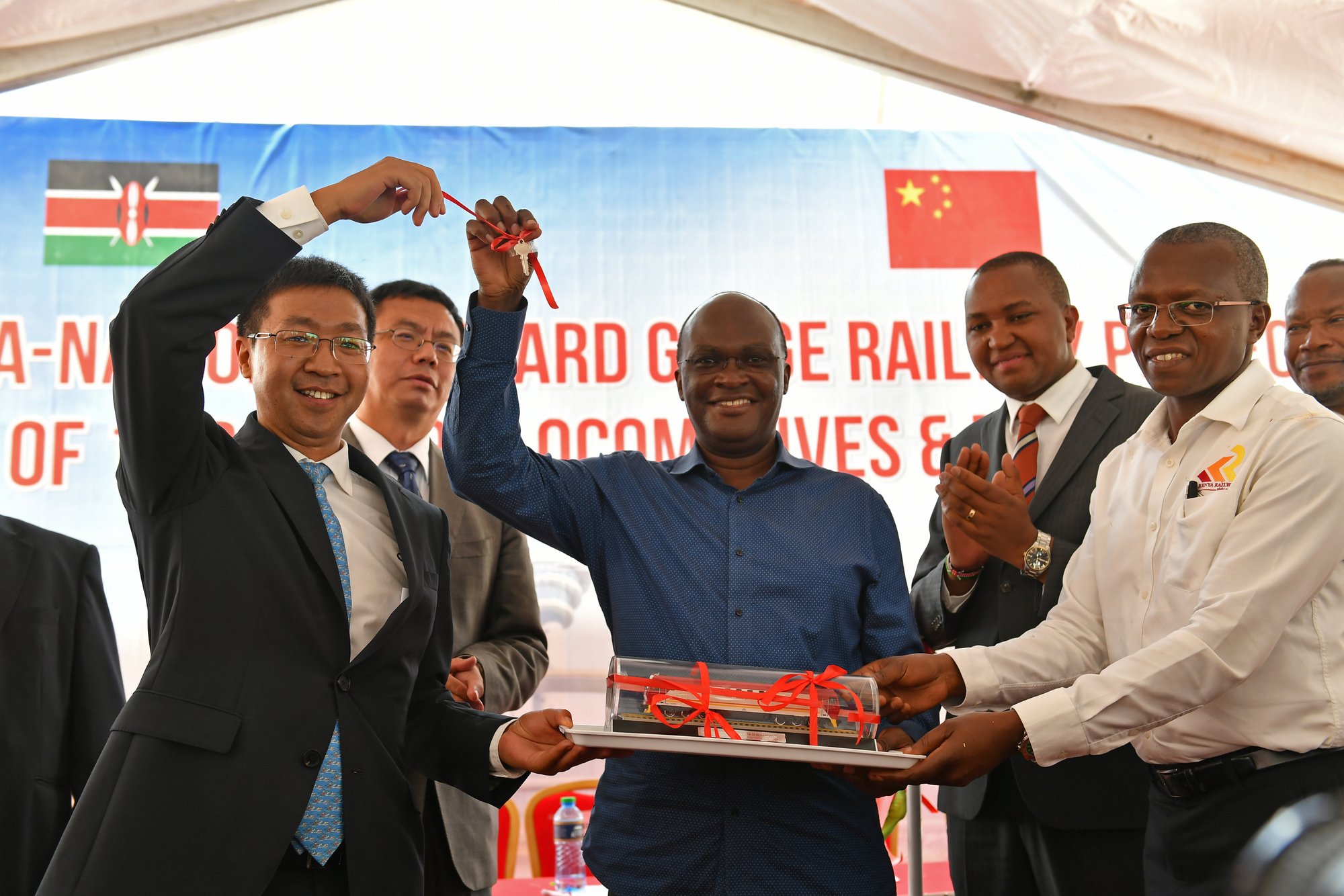

Celebrating Kenya’s new China-built and funded railway. Credit: Xinhua/Sipa USA

At the Mombasa terminus of Kenya’s new 293-mile, £2.5 billion Chinese-built and funded railway, which runs between the coast and Nairobi, stands a statue of the Chinese explorer Zheng He, who reached the Kenyan coast in the 15th century. Most of the travellers who pass through, however, assume it depicts Chairman Mao, the second most recognisable Chinese man in Kenya after Hong Kong actor Jackie Chan.

The confusion is perfectly emblematic of the distance China still has to go to connect with its African partners. China has long been involved with Africa, generous with aid and direct investment. According to the China Africa Research Initiative of the Johns Hopkins University, $94.4 billion worth of loans was extended from the Chinese to African governments and state owned enterprises between 2000 and 2015.

But the cultural divide is massive, as evidenced not only by the statue but also by mistranslated station signs. One of which mistranslates “No pets allowed” as “Hakuna kipenzi kuruhisiwa”– a ban on heavy petting.

The disconnect is partly because, in China’s quest for ever greater global influence, it has adopted a bland, business-like approach to soft power, encouraging citizens of other countries to admire its values, but without seeking to adapt to those societies. It views these places in the same way Victorian Britain and her contemporaries saw Africa a century ago – as a land inhabited by uncivilised people in need of a role model.

Beijing’s approach, which has prioritised economic development over socio-political progress, ignores the complexities of the postcolonial societies it is investing in and is storing up trouble.

Earlier this year, for example, a racist skit screened on Chinese state broadcaster CCTV to an audience of more than 700 million. In the 13-minute comedy sketch, marking the opening of the new train line, a young black woman dressed as a train stewardess asks a Chinese man to pose as her husband so her mother would stop pestering her to marry. The young woman is played by a black actor, the mother is an Asian actor in ‘blackface’ with a traditional outfit and fake buttocks, accompanied by another African actor in a monkey suit. It was leaden with stereotypes about China and Africa. Unsurprisingly, Twitter nearly fell over with the outrage.

It wasn’t an isolated example. There was also an unpleasant exhibition in Wuhan which featured photos pairing Africans with animals, causing international upset, as well as an awful detergent ad in which a black character was washed white.

When the train sketch made the news, it caused outrage among Kenyans, though China and her defenders were quick to claim that it was not racist. More than one official, including a Chinese diplomat in Nairobi, said that it was confected outrage by Western media – to “drive a wedge between China and African countries”.

But Sino-Africa relations are being shaped by such perceptions, and tensions are simmering. Not that these tensions are new.

Defending the detergent ad in the Hong Kong Free Press, black African writer Innocent Mutanga said that the West had a far longer history of racism than the Chinese, for whom he argued that whiteness is about class rather than racial superiority. But the implication in China is the same: black means poor (because rich people didn’t have to work, they had fairer skin than those who worked the fields).

And in any case, China does have a history of enslaving black people, which it chooses to ignore: the first Africans known to have entered China were slaves, shipped by Arab slavers in 977. In Notes on Pingzhou, an account of foreign trade from 1119, author Zhu Yu describes slaves as “superhuman in strength but subhuman in intellect and habit” and talks of “domesticating” them.

When China re-emerged on the global scene after centuries of insularity, racism followed. The earliest African students in China in the 1960s and 1970s were discriminated against. In 1988, there were widespread demonstrations opposing African students in the eastern Jiangsu province of Nanjing.

Prejudice against African men having contact with Chinese women echoed the “black peril” fears during the colonial decades. China even introduced a raft of policies after the demonstrations, which included a race-specific nighttime curfew, as well as access limits to Chinese girlfriends.

In modern China, there is a growing xenophobia against black Africans. Africans living in China have written about being described as “hei gui”, black devil, and being assumed to be criminals.

In Kenya, meanwhile, China’s attempts to transfer its overcapacity has skewed competition and stifled formal markets. It is also seeking dominance over informal ones. As a result, there have been protests calling for an end to the Chinese invasion as cheap Chinese goods have flooded the market, and small-scale Chinese business people have set up shop. In 2012, a photograph of a Chinese man in Nairobi selling roasted maize went viral. Traders took to the streets bearing placards saying: “The Chinese must go”.

China will claim that this is outrage manufactured by a Western media, but many Africans have spoken out about the crass and offensive skits, ads and exhibitions.

Returning to that station in Kenya, where Chinese officials chose algorithmic translations over local human interaction, and got the signage so very wrong, it is also notable that the Zheng He statue was made in China and installed by Chinese sculptors. China prefers its own one-size-fits-all approach to infrastructure projects, instead of adopting cultural elements sensitive to a local economy. Likewise, it is ignoring the fact that the debt model it employs is only worsening, rather than alleviating, the glaring inequality in African countries.

The echoes of the past are surely too strong to ignore.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe