A day of action in support of migrant workers and EU citizens. Credit: Jack Taylor/Getty

The fascinating new immigration opinion data provided by UnHerd exposes the foundations of the new ethnocultural issues reshaping the British electorate. Whether we label this “open versus closed”, “globalists versus nationalists”, “anywheres versus somewheres” or “cosmopolitans versus nativists”, the new cleavage is overshadowing the old economic Left-Right divide.

Small-c conservative working-class voters have migrated to the Conservative Party because of immigration and Brexit. On the other side, successful educated cosmopolitans opt for Labour or the Lib Dems.

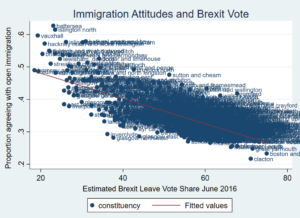

As a number of academics, including me, have pointed out, apart from attitudes to the EU, nothing predicts whether someone voted Leave better than their views on immigration. This shows up clearly in UnHerd’s data.

For instance, as figure 1 reveals, 55% of the variation in immigration attitudes across constituencies can be explained by Brexit vote share, a powerful association. The relationship is especially strong toward the top left, with the strongest Remain seats far more pro-immigration than elsewhere.

Figure 1

Sources: UnHerd Britain / Brexit data from: “Areal interpolation and the UK’s referendum on EU membership”, Chris Hanretty, Journal Of Elections, Public Opinion And Parties, Online Early Access, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2017.1287081

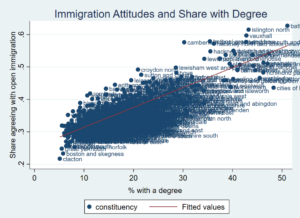

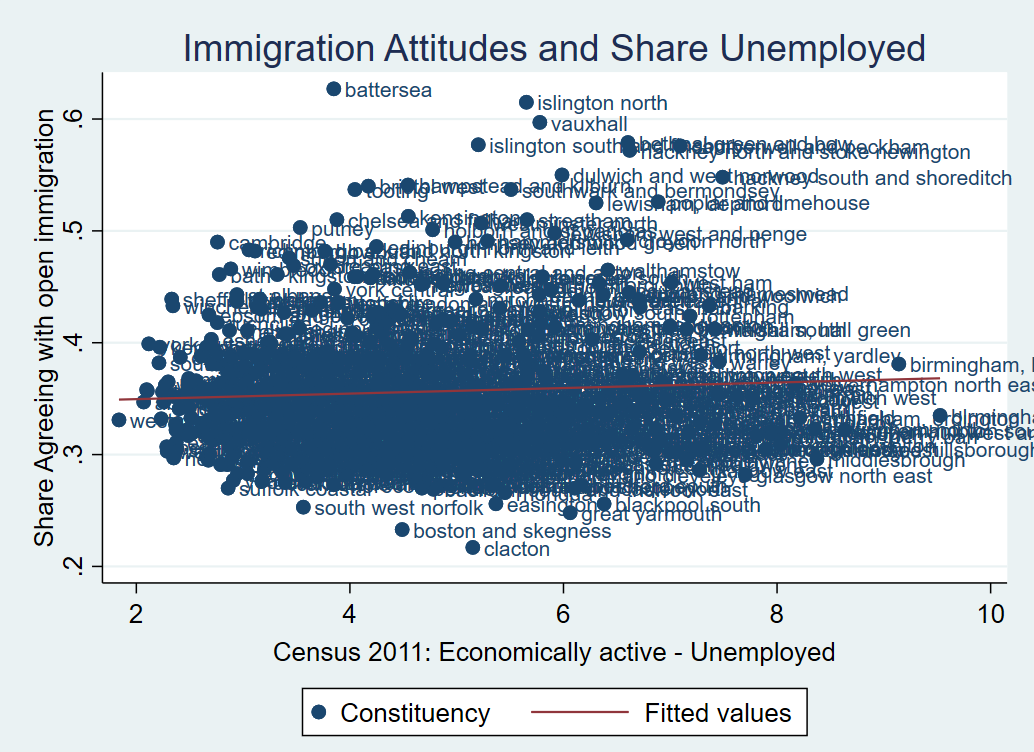

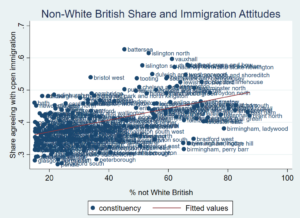

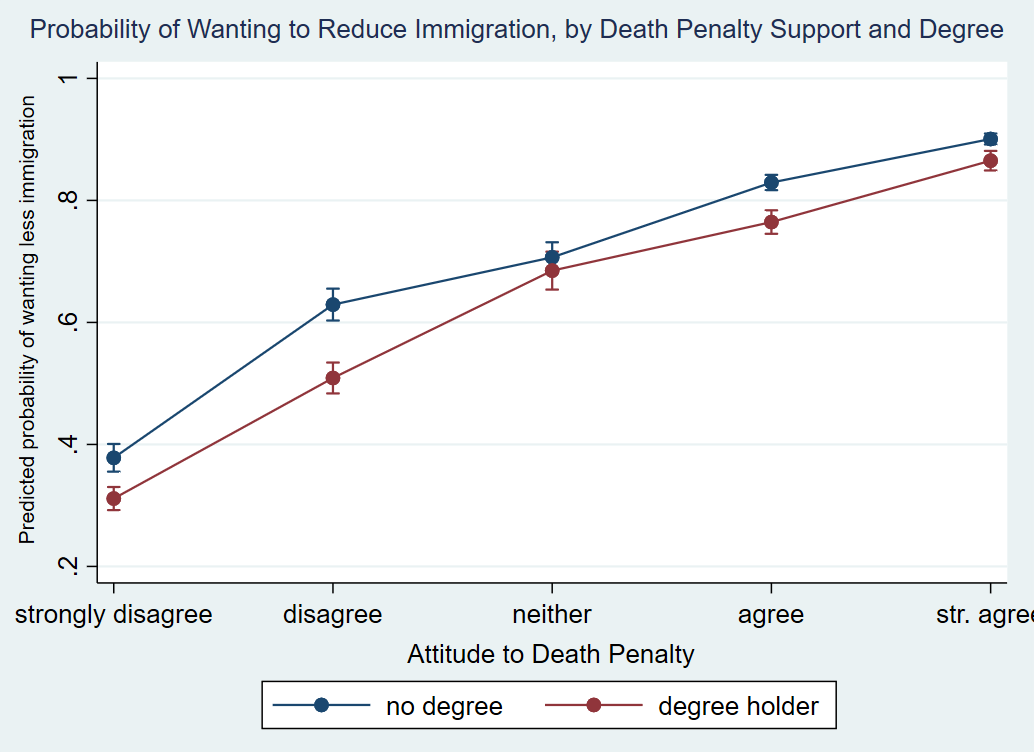

This rising cultural cleavage made a powerful impact in the 2017 election despite the fact Corbyn’s far-Left image gave prosperous voters a strong incentive to vote against him. But what makes Hackney different from Boston on immigration attitudes? At the constituency level, this is about demographics, of which the key ones are, in order of importance: the proportion with degrees, the level of ethnic diversity and average age. The share with a degree varies from under 5% in Clacton to over 50% in Battersea. Immigration attitudes largely track this measure, as figure 1 shows. The reason higher education is so important is not because it boosts earnings, but because it is a measure of psychological openness and a liberal worldview, both of which incline curious minds toward the pursuit of higher education.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe