Mural depicting the kiss between then Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev (L) and East German leader Erich Honecker is projected on a stretch of the Berlin wall. Credit: John Macdougall / AFP / Getty

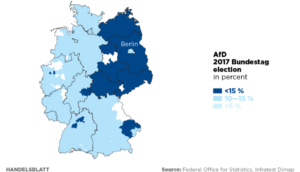

This month marks 30 years since the Berlin Wall fell, and once again Germany’s radical nationalist AfD has performed well in a state election, scoring a second-place 23.4% in Thuringia. This is almost exactly the same as they achieved in Saxony-Anhalt, on top of 23.5% in Brandenburg, 20.8% in Mecklenburg and that whopping 27.5% in Saxony.

Die Linke, Germany’s equivalent of Corbynite Labour but (happily for Germany) its very own party, also did well in Thuringia — spectacularly so, hitting 31% and becoming the strongest single party in a state administration for the first time.

So, judging from those results, is German liberal democracy caught in a fatal pincer-movement of the populists, who claim to be mortal enemies but are both anti-EU, anti-NATO and pro-Putin?

Recent election posters from the populist “left” and “right”, accusing the establishment of NATO warmongering.

Well, yes and no. It depends on how you look at it; or rather, where you look at it. For talking about German politics nationally is becoming almost as meaningless as talking about the UK as if it were, in our days, a single political unit.

A map of the 2017 Bundestag election shows this division with extraordinary clarity.

But why do Easterners vote so differently from Westerners, thereby upsetting the political applecart of Europe’s most important economy? Right across the respectable political spectrum, Germans seek desperately for easy, modern explanations.

Conservatives tell themselves that the East Germans did, after all, unfairly pay the final bill for 1933-45, being traumatised by half a century of occupation by the Red Army, so that it’s no surprise they feel hard done-by; free-marketeers in the German ordoliberal tradition, which assigns the state a more active role in enabling and regulating than Anglo-Saxon classical liberals do, argue that more should be done to attract — effectively, to bribe — private enterprise into the old East.

And then leftists claim that former East Germans are simply driven by righteous if misdirected anger at having been de-industrialised by predatory western capitalists, who asset-stripped perfectly viable ex-GDR State businesses (although they’d struggle to find any actual viable examples). Because of this they thus deserve massive, ongoing state help.

Meanwhile, the old West just keeps on footing the bill, and since 1990, well over €2 trillion has been pumped from Western taxpayers to the East. The so-called Reunification has dragged West Germany back into the role which Bismarck assigned it: to subsidise the economically moribund East because it is their patriotic duty.

Western German voters, rather sick of this, are more and more wary of keeping up this settlement, on top of their traditional role as paymasters of the stable Europe from which German industry benefits so greatly. Yet the Prussian myth of “reunification” has trumped economic reality, which goes to show something we in Britain should know all too well: that there is nothing worse for a country than to misunderstand its own history.

Southerners in the USA dwell on the Civil War as if it were yesterday, but who in western Germany now recalls that Germany was never “united” in the first place? It was militarily defeated by Bismarck’s Prussia in 1866, after which Austria was kicked out, some of the beaten states simply annexed by Prussia, and some allowed a sort of half-life until 1871. Who, today, dares to say that the only definition by which East Germany was more German than Austria is Bismarck’s definition?

The founder of West Germany, Conrad Adenauer, knew his history. After the First World War he begged the French and British to help him split Prussia off from Germany. When he had to visit Berlin, he would always draw the curtains of his train compartment as he crossed the fatal River Elbe, muttering “Here we go, Asia again!” (“Schon wieder Asien!”) After the second war, though obliged in public to support re-unification, he told the British most secretly that he was determined it should never happen.

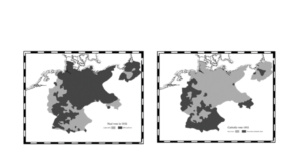

The most obvious sign that there are two countries is the confessional divide between Catholics and Lutherans. Anyone who doubts how significant that division is should just look at a map of the Nazi vote in 1932 superimposed onto a map of the Catholic population according to the 1934 census. They are, to all intents and purposes, mirror-images.

Religion in Germany is really just a sign of the Germany you come from: the one which partook centrally of western European civilisation right from the start — or the one which has a completely different trajectory. The classic line between these two Germanies is the River Elbe, which the Romans thought the natural limit of Germania. Charlemagne’s restored “Roman” Empire ended there, too.

While early medieval western Europe was developing its unique signature, the power-sharing of international Church and national-state, the lands beyond the river Elbe were still populated by pagan, illiterate tribes. No real attempt was made to exert German control and settlement beyond that point until 1147; Cologne had already been a flourishing western European city for 1,200 years when the first German conqueror-farmers reached Berlin.

If there’s one thing worse for everyone than a successful mass-colonisation, it’s a half-successful mass-colonisation — ask anyone in Ulster. East of the Elbe, the Germans never entirely supplanted the Slavs (some, the Sorbs, remain even in the truncated eastern Germany of today, just north of Dresden).

For 800 years, generation upon generation experienced this same colonial reality. Within living memory, whether you called your hometown Posen or Poznan, Danzig or Gdansk, could be a matter of life and death, on both sides.

So while no one ever disputed that the western Germans belonged where they were, the eastern Germans always knew that the helots might rise up one day. Like the poor whites of the American South, the settlers of Rhodesia, the Protestants of Ulster or the Pieds-Noir of Algeria, the eastern Germans came to believe that they must, above all, have a political elite of their very own tribe, ready to respond instantly and ruthlessly if their supremacy was ever challenged.

Social psychologists call this “social dominance orientation”, the cultural belief that “we” have to at all costs lord it over “them”. The Germans of the east came to accept rule by a caste of warlords — the famous Prussian Junkers — and, later, the new Lutheran paradigm of a state which controlled its very own Church and against which there was hence no appeal.

Not for nothing did Friedrich Hayek see Prussia as the template for all modern totalitarian states, whether of the Left or of the Right. Max Weber constantly referred to a place he called Ostelbien, East Elbia, palpably different, for all its local variation, to ciselbian, western Germany

Of course, psychologists, philosophers and sociologists can all be wrong and often are. Electoral maps, however, do not lie. They show that ever since Germans have had votes, eastern Germans have voted very differently from western Germans.

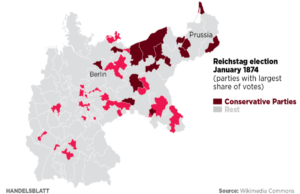

Under the German Empire (1871-1918), the Prussian Conservatives — conservative in this context meaning supporters of royal and militarist rule under an agrarian Junker elite — depended almost completely on votes from the East, having scarcely any traction at all in the West.

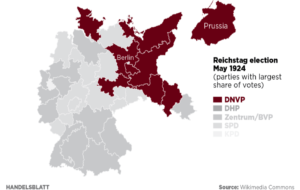

The First World War changed nothing. In the first normal elections of the Weimar Republic, the extreme Prussian conservatives of the DNVP (officially anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic, violently antidemocratic, their members implicated in several high-profile political murders) were the second largest party nationally but — exactly as with the AfD today — that position was entirely dependent on votes from the East.

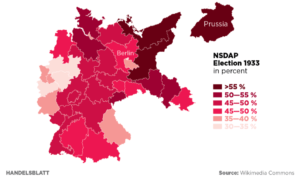

And when the deluge finally came in 1933 it was, again, only thanks to heavy votes in the East that Hitler got 43.9% nationally, enabling him (with support from the rump DNVP) to seize power by semi-constitutional means. If the whole country had voted like the Rhineland or Munich, he could only have attempted an armed coup, which the Army would have crushed.

In short, wondering how voters in the East of Germany would go for antidemocratic, authoritarian and anti-EU politics, while the West of Germany sticks with the CDU and goes Green, is like asking how it can be that a Democrat should win New York at the same time as Arkansas and Alabama vote Republican. It’s all about cultural history, and Germany has its very own version of the Mason-Dixon line, but far older and deeper.

This is bad news, of course, for Germans wedded to the notion of a united and more or less culturally homogenous state. On the other hand, it is very good news for Germans who fear that the politics of eastern Germany might spread. They won’t, any more than New York is ever going to be an Open Carry state.

If the West holds its nerve — that means, on a practical level, no preferential financial treatment and never entering coalitions with the AfD or Die Linke, however awkward that may make things — the “spirit of the East”, as Adenauer called it, is no longer strong enough to pull Germany away from its natural place at the heart of Western Europe.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe