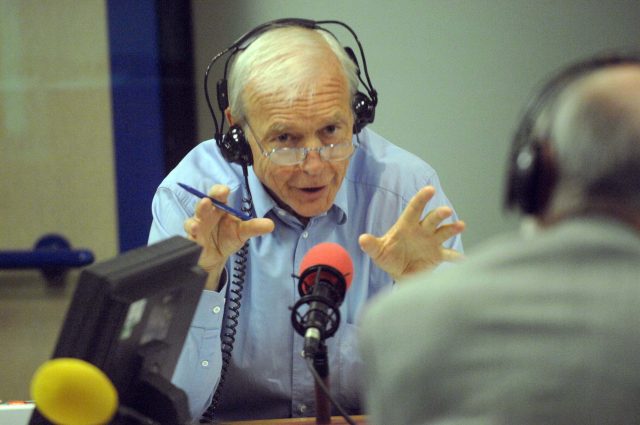

So, goodbye, John Humphrys. Throw away that alarm clock set for 3.30 am. For over three decades, I have woken up with you beside me. You were a reassuring presence, a kind person, big hearted — it’s true — and with one of the most finely tuned bullshit detectors of any of them. Mornings won’t be the same without you.

The Tory svengali Dominic Cummings may think the Today programme is no longer required listening for the political class, and others may deride Humphrys as a dinosaur, politically incorrect and overly hectoring of guests. But I have always found him charming and fair — even when I was on the receiving end of one of his kickings.

We debated religion a lot, both on the radio and around his kitchen table. He even wrote a book about it: In God We Doubt: Confessions of a Failed Atheist – the subtitle, as he acknowledges, he lifted from me.

But it was his interview with Rowan Williams that I will remember the most. It followed the Beslan massacre in 2004. Chechen militants had taken over a school and massacred a great many of its children. Humphrys’ opening question to the Archbishop was a classic: “Where was God in that schoolroom?” Deceptively simple, direct, short, devastating. It was also the question of a man who was the first reporter on the scene after a mountain of coal debris had collapsed upon a primary school in south Wales in 1966, killing 116 children and 28 adults. And you could hear that in his voice.

The archbishop didn’t answer straight away. He paused for what seemed like an eternity, some might say unable to answer. I would say: he was giving that impossible question, and the deaths of so many children, the respect it deserved. It wasn’t a cheap question and it didn’t receive a cheap reply. In one moment of electrifying radio, the so-called problem of evil – something debated by philosophers since time immemorial – came alive. “That interview led to … the biggest reaction by far to any programme I have done for the BBC in more than 40 years of broadcasting,” Humphrys later wrote.

It may not be this for which he is remembered. He skewered Tony Blair, in 1997, on the political TV show On the Record for accepting a donation to the Labour party of £1m from Bernie Ecclestone. Labour, which had just come to power, soon after exempted Formula One racing from a tobacco advertising ban. “I think most people who have dealt with me think I am a pretty straight sort of guy, and I am,” said Blair in the interview. A quote that hung over the rest of his political career.

Humphrys’ destruction of his then boss, George Entwistle, for his failure to stop a Newsnight programme that mistakenly implicated a Tory peer in allegations of sexual abuse – the so-called “dead man walking interview” — was an example of speaking truth to power of the highest order. Entwistle resigned as director-general of the BBC 12 hours later.

Humphrys’ passing feels like the end of an era. Paxman, with his similarly pugnacious approach, went fishing years ago. Perhaps it points to what Cummings said, about how these set pieces and titanic clashes of male egos on the mainstream media no longer have any effect on voters. Interviews only matter when they can be culled for 20 second ‘gotcha’ moments perfect for social media. But such clips don’t change people’s minds about anything by way of reasoned argument – they are little more than digital hand grenades bounced around on Twitter.

So is the political interview past its sell by date, now no more than old fashioned gladiatorial combat for a handful of political anoraks? I hope not.

I have, with Confessions, begun to appreciate much more what is involved in making an interview work. I know, for instance, that I have a fatal weakness as an interviewer: a desire for conviviality. This makes me hesitate to ask a question that may introduce a little too much tension in the exchange. What Humphrys manages to do – and others who have become masters of their art – is robustly to challenge their guests without boorishness, yet also recognising that s/he is an agent of the listener to whom politicians are accountable and who don’t tune in for a party broadcast.

Politicians have become adept at not answering questions. Their strategy is commonly: acknowledge, bridge, comment. Responding to a line of inquiry they do not like, they first nod to the question being asked, as if this was to answer the question, then bridge to the thing they really want to talk about – something like, “but the most important thing here is…” – then comment on that, with long sentences and few full stops, thus not allowing the interviewer the opportunity to return to the question. The best interviewer is able to disrupt the way interviewees have come to ‘manage’ conversations.

And at this, Humphrys is the master. He doesn’t care too much about being liked. And so he often isn’t. But he is right when he once said that the key quality for a good interviewer is curiosity. And that’s precisely the problem with the social media use of interview clips – they have substituted curiosity for the gotcha moment and a re-enforcement of our own prejudices. And with this, the world becomes a smaller and a far less interesting place.

Which is why the Humphryses of this world are now more necessary than ever. And why we should be grateful that Andrew Neil has been given a new show. In a political climate saturated with bullshit – or post-truth, as some like to call it – old school professional sceptics help us all to stay connected with the truth in a world of constant and increasingly sophisticated deception.

There is something singleminded, uncomplicated even, about the determination not to be side-tracked by fancy explanations or charming presentations. Not “why is this lying bastard lying to me” – that is too cynical and disrespectful. But stay focused, come prepared, be persistent, listen hard, remain curious, and keep things simple – there is often evasiveness in complexity. These were the threads Humphrys followed to great effect.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe