Because we reason by heuristics and emotions – the hot, fast, cognitively frugal elements of what psychologists call ‘System 1’ – what the question actually elicited in the great majority of cases was your social outlook: cosmopolitan, individualist globalists vs rooted, communitarian nationalists. This is true for both Leavers and Remainers, and we’ve all spent three years rehearsing the reasons why our side is right.

I tend to follow the BBC’s output for roughly the reason that Kremlinologists read Pravda: that it’s the best way to know what the powers that be think. A recent piece, Allan Little’s ‘Looking for Brexitland’, had some insight, however:

“Brexit has driven a fracture through both the two big Westminster parties. The divide in the House of Commons might still, formally, be between a Conservative government and a Labour-dominated opposition. But in the country, politics has realigned. The divide out here, beyond the Westminster bubble, is between Remainers and Leavers.”

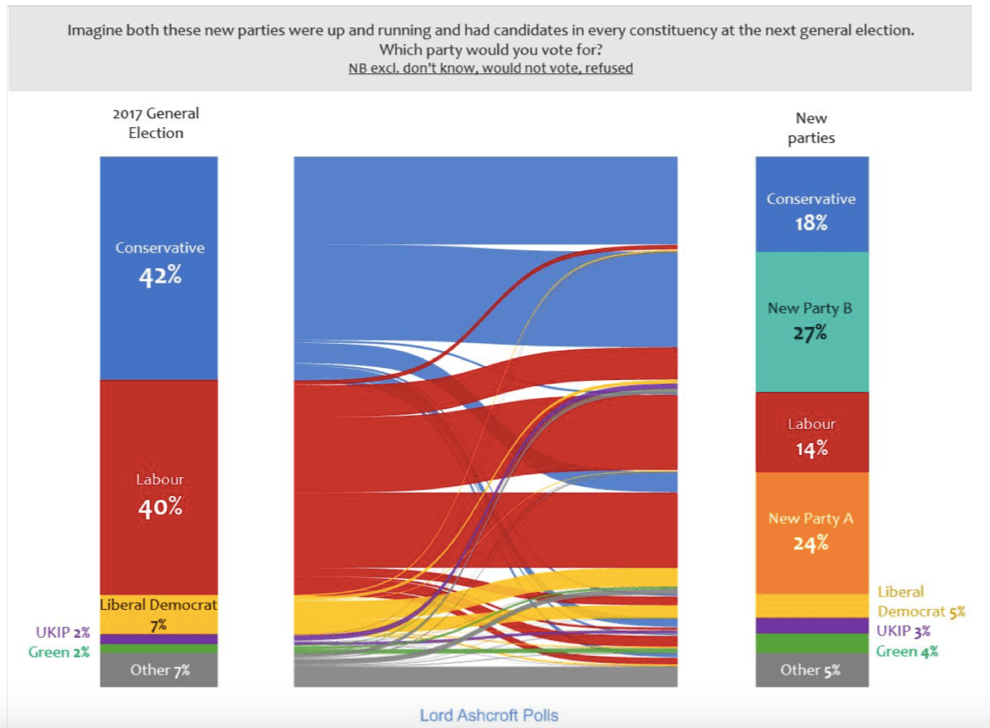

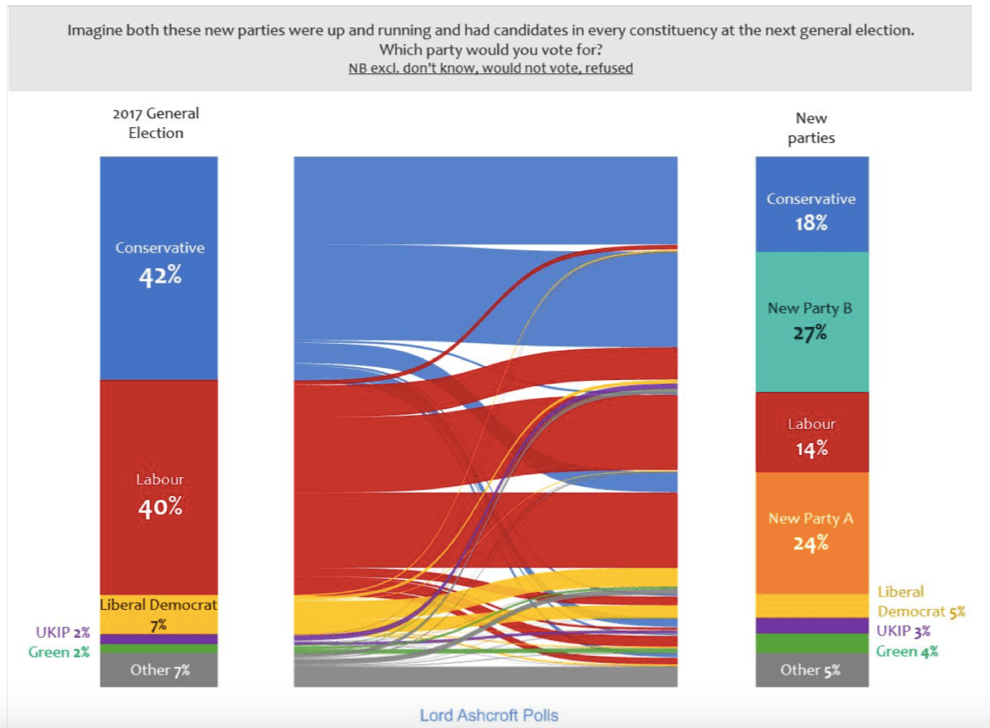

Some new polling by Michael Ashcroft has confirmed with data what Little – and you and I – have discerned anecdotally: that there has been a decisive shift towards the priority of the social cleavage over the economic.

Ashcroft showed two things. First, voters’ mental associations for the two existing parties are effectively unchanged in a decade. The Tories are the party of entitled aristocrats; Labour are the party of welfare scroungers. Both are still defined by their historic economic positions.

Second, he asked people to imagine there was a new offer. ‘New Party A’ would be supportive of immigration, want action on climate change, promote rehabilitation in criminal justice, support international aid and supranational institutions generally. ‘New Party B’ would reduce immigration, argue that climate change had been exaggerated, take a tougher line on law and order, spend the aid budget in the UK instead, think that traditional values had been neglected and that the UK was becoming a nanny state. Their respective positions on relations with the EU are obvious. Call these the ‘Progressives’ and the ‘Nationals’.

The results were striking. In this fictional contest, Conservative and Labour are reduced to rumps, at 18% and 14% respectively. The Progressives come second, at 24%. The Nationals come first, at 27%. The Progressives and the Nationals lead on social issues, while Conservative and Labour lead on economic. The point is that making social issues salient leads to decisive change in how people say they would vote.

What are the implications of this for the present political moment?

Because social issues now matter more than economic ones, for more people, there is a realignment coming at some point. The offer that the two parties give to the electorate will shift from being rival answers to how to cut (and bake) the pie. It will shift to a contest over which conception of society – diverse versus ordered – wins out. The precise mechanics of how this will happen are uncertain, but that it will happen just reflects the fact that one’s position on the social cleavage now matters to people.

For good or ill, the Conservatives have been the custodians of Brexit. If they fail to deliver it, in terms that Leavers recognise, they will permanently mark their brand as Merchant Right – interested in self-enrichment and disloyal to the country – and not to be trusted by those concerned for an ordered, communal focused view of society. That we are looking at a super-soft Brexit reflects Conservative MPs’ priorities, where pro-business and socially liberal outlooks are the norm. It does not reflect that of the majority of their voters.

Among the many lessons that people ought to have learnt in 2016, one was delivered with force to Paul Ryan: parties that fail to represent their electorate’s actual views are in a precarious position. In the Republican party’s case, they were vulnerable to hostile take-over due to the primaries system.

In the Conservative party’s case, if it fails to pivot to the new reality, it will be vulnerable to political entrepreneurs who offer, outside the party, the social conservatism that a large portion of the electorate want. Labour’s offer is already defined by the kind of social liberalism that appeals to the tertiary educated who spend their time manipulating symbols on computer screens. This is not territory that the Conservative party will be able to win on, nor ought it to want to. If the Conservatives fail to provide a genuine alternative, someone else will.

Equally, if they manage to pivot to the new reality, there is a significant opportunity. This would be good for the party. Insofar as the coalition that the party would then provide is a moderating influence on the excesses of each wing, it would also, I think, be good for the country.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe