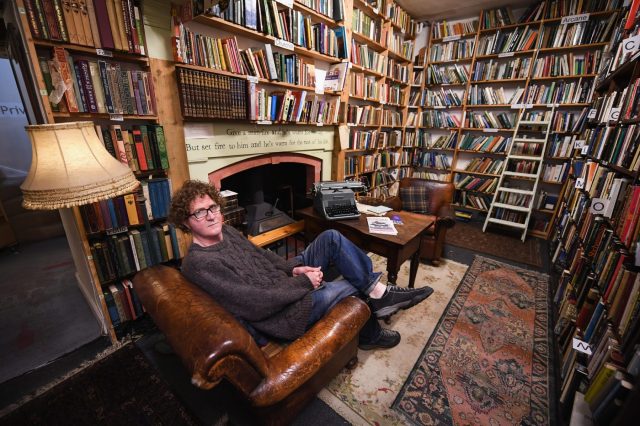

Shaun Bythell owner of The Book Shop in Wigtown, Scotland. Wigtown has had official ‘book town’ status since 1998. (Photo by Jeff J Mitchell/Getty Images)

Twenty-one years ago, Wigtown, a small settlement on the southwest coast of Scotland, decided to try a new way to regenerate the ailing community. Tucked away on the edge of the Machars peninsula, the town of just over one thousand people became the second place to become what is known as a national “Book Town” – a place dedicated to, and sustained by, people’s love of the written word.

“It’s had an enormous impact,” says Joyce Cochrane, who runs one of more than a dozen bookshops in the town with her husband, Ian. “I grew up six miles down the road, and I can remember Wigtown as it was when I was growing up in the Sixties and Seventies. A lovely wee town but when the Seventies and Eighties came, so did the decline.

“Before you would only come into Wigtown for an ice cream. Small family businesses were closing, and nobody was there to take over because my generation – I was born in the early Sixties – either moved away or had bigger ambitions. You couldn’t sell a property. Before we became a book town, you couldn’t even give it away; nobody wanted to live here. Houses were boarded up. It was like a ghost town, really.”

The reason for the town’s slow death would be familiar to many: the Beeching Report of the mid-Sixties which prompted the closure of over half of Britain’s railway stations and more than 30% of its tracks. Before its closure on 14 June 1965, southwest Scotland’s main rail route, the 73-mile arterial line between Dumfries and Stranraer, had serviced some of the country’s most remote communities and employers. The Wigtownshire railway – a branch line that connected at Newton Stewart in the north and ran to Whithorn in the south – served the east coast of the Machars peninsula and was, with the area’s poor quality roads, Wigtown’s primary connection to the outside world.

In the decades after the closure, two important local employers – Bladnoch distillery (which has re-opened and closed several times, and is recently up and running again) and the Co-operative Creamery – succumbed to the same fate. By the 1990s the town had one of the highest unemployment rates in Scotland, was a shadow of its former self and was blighted by derelict homes and shopfronts.

Joyce remembers vividly when things began to change. “I was a librarian around Edinburgh when my Dad had been watching the developments in the town and called to say that a bookshop had opened and, I’m embarrassed, but I burst out laughing.”

The idea for turning small, isolated communities into “book towns” began in 1961 when Richard Booth opened Hay-on-Wye’s first second-hand bookshop in an old firehouse. His was the first of many to set up in the small Welsh town, and by the 1970s it had earned the moniker “The Book Town”. The Hay Festival followed in 1988 and in the following 30 years has gone on to become one of the world’s premier festivals of reading. A truly remarkable achievement.

By the middle of the Nineties, the idea to replicate Hay’s success in Scotland had taken hold. Six impoverished towns were chosen as candidates, and an international panel settled on Wigtown for the accolade. By 1999 the new Scottish Parliament had recognised it as the nation’s official ‘Book Town’ and change was underway.

At first, the reaction wasn’t universally positive. Most people were unconvinced that it would do much good, or that anybody from further afield would be interested. News that the designation would be followed by a Wigtown Book Festival the same year didn’t do much to enthuse the naysayers. Who would come?

Lots of people, it turns out – at least eventually. In its first year, the event took a modest £950 in ticket sales. In 2006, the festival attracted 6,000 visitors, and in its 20th year in 2018 it attracted 29,000, generating £3.45 million for the regional economy. A Hollywood film company has even bought the rights to two books by locally based authors with the idea of combining the two stories to create a movie or a TV series. Even in the bleak midwinter, there is a definite buzz about the place.

The contrast with the town I’ve heard about from 30 years ago is remarkable. There are visitors in the bookshops and in the bar of the town’s single hotel. The streets are full of well-maintained, picturesque cottages – now a compliment to, rather than a distraction from, the equally stunning sea and mountains they sit among. Some visitors are here to buy them, something I’m told would have been unheard of two decades ago. The scepticism surrounding the town’s transformation has almost evaporated, too, along with much of its deprivation.

One of Wigtown’s most notorious draws is The Open Book, the world’s first and only rentable bookshop – currently booked up for three years, with 700 people on the waiting list. Celia, the current tenant and a documentary film-maker from New York, booked her week-long stay three years ago after reading an article on BuzzFeed and arrived the day before we met. We’re both outsiders, but within minutes we’re sharing our love of the place and affectionately gossiping about the locals. “I think this is the nicest town in the world,” she tells me, a pin for every tenant stuck in a map of the world behind her. Like her, a lot of them are Americans; about half come from outside the UK.

Despite the town’s relentless improvement, there are still many things that threaten to hold it back. While the craggy beauty of Galloway can easily compete with Hay’s picturesque setting, Wigtown is in one of the most remote parts of Great Britain. The nearest train station in Stranraer (the only one in Galloway) is 40 minutes away by car, or between an hour and four hours on a bus. The nearest airport is Glasgow’s – two hours away, or six to eight hours if you use public transport. By contrast, sitting on the border with England, Hay-on-Wye is within relatively easy reach of several big centres of population.

When I ask about what’s limiting the town’s development, the answers are near-identical and come without pause. “We’ve got a lot of sea, a lot of mountains but not very many people, so Hay-on-Wye is a much wealthier place,” says Shaun Bythell, bookseller, renowned author and perhaps the town’s most famous character. “We are limited by infrastructure so the festival can only get so much bigger; it’s just so remote and hard to get here.

“My friend looked at my turnover over 15 years and mapped it with the price of petrol, and there’s an exact match. Even when he checked it against various other factors, it was the price of getting here that made the crucial difference; there’s no question that transport is the problem.”

The lack of varied employment is a barrier to growth, too. Although one of the two big employers that left has now returned, the small size of the regional economy means that high-paying work is a rarity. Running your own bookshop is no way to make a fortune, so that avenue remains permanently closed to anyone preferring a high-flying career over the hermetic bliss of shifting hardbacks, however romantic an option it seems. Just like anywhere else, the ambitious will leave, as they always have done.

“In some ways you could argue we’re a little bit ahead of the curve. Places are going to have to face the same problems Wigtown did 20 years ago – look at their High Street and say ‘What is this for?’” says Adrian Turpin, the Wigtown Book Festival’s artistic director, who is currently gearing up for next week’s annual Big Bang Weekend, an arts, literature and science event aimed at livening up the spring calendar.

“That remoteness can also bring value,” he tells me. “The important thing is that Wigtown feels like somewhere that’s different to everyday life. It’s more important than ever to have those meaningful public spaces. So the more we build up those elements: the culture; the literature; the history – the better we’re doing our job.”

There are lessons here for some towns, although not all. Two decades ago, Wigtown was collapsing, and yet providing the area with its own niche has not only stalled but dramatically reversed its decline. The locals are almost universally optimistic, and there is a profound sense of a town going somewhere it wasn’t before. However, the speed at which it travels will be decided by something far more tangible than optimism: money, roads, and railways.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe