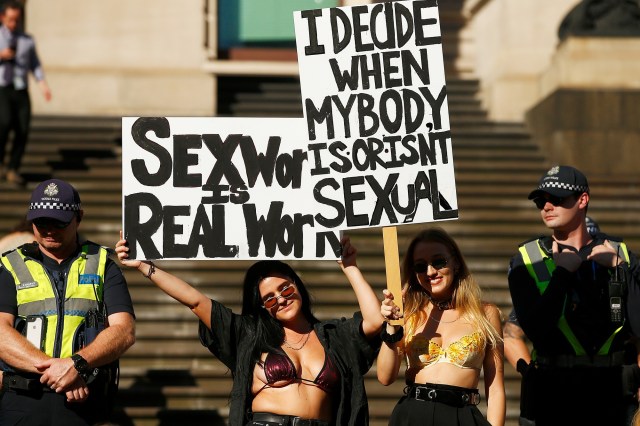

(Credit: Daniel Pockett/Getty Images)

I’m a feminist and I’m tired. Not of men, but of women. Of fellow feminists who want to deny the voices and stamp on the livelihoods of other women. Funnily enough, they don’t attack the voices and livelihoods of women who make monstrous sums of money from their brains, which would, even at a time of growing class warfare, cause uproar. They instead deny the voices and strangle the livelihoods of women who make money from their bodies.

The latest such attempt is visible in the “shocked” response to a sex worker support group – SWOP – being allowed a stall at Brighton University freshers’ fair. Quoted in The Guardian, feminist writer Julie Bindel argued “This is beyond disgraceful.” Sarah Champion MP took to Twitter to argue that Brighton University were “colluding with organised crime & abusers”. In fact, SWOP was making people aware of a support service for sex workers and handing out free contraception.

This is not the first time that feminists have come down hard on sex work. In the US, recent legislation has made it much harder for sex workers to have bank accounts and to use the web to advertise their services, share information and screen clients. Unlike virtually every other piece of Trump-era legislation, prominent feminists here in Britain have decided that it would be a good idea to import this legislation into the UK. Sarah Champion MP is leading the way.

In response, sex workers have held protests in Parliament Square. But few people seem to be listening – a bunch of clever women in positions of privilege are ignoring the voices of some of the most marginalised and certainly most stigmatised women in the country. I would be ashamed to be associated with such elitism, hypocrisy and unfairness.

The argument might at first seem innocent: that involuntary sex work needs to be tackled and that by trying to wipe out sex work you can reduce sex trafficking. Not only is this naively utopian and economically illiterate, but those recommending such legislation have failed to listen to and so properly consider the potential effect on voluntary sex workers. Economists Maria Laura Di Tommaso and Marina Della Giusta, for example, who have studied the sex trade for 15 years, found that the risks for sex workers, including of violence, “are higher where prostitution is criminalised”, and that criminalisation makes the detection of trafficking harder to identify.

Those who deny sex workers a voice trot out the same old mantra: that no sex worker is ever doing sex work voluntarily; that, in other words, voluntary sex work doesn’t exist. The arrogance is remarkable: how can any woman presume to know what is going on in the mind of another woman, let alone the many thousands of women who do indeed classify themselves as voluntary sex workers?

The only way that I can imagine another feminist justifying such a position is on the basis that sex work is ‘wrong’. I have no time for such moralism. Not only is it impractical and judgemental, it is elitist and hypocritical: why should I be able to make money from my brain whilst stamping on the livelihoods of others who make money from their bodies? If you think paying for sex is “wrong”, then don’t buy or sell it; it’s that simple. Don’t instead try to restrict the ability for others to choose differently.

Before anyone pipes up with the argument that sex workers generate a cost for other women, such as by encouraging men to see women as sexual objects, let me pose a series of questions: would you equally want to stop women from doing cleaning and caring jobs on the basis that it such tasks might, as a result, continue to be associated with women? And, would you stop really clever people from using their brains because it might ‘hurt’ others by making them feel “stupid”? And what about men who do heavy lifting jobs, like removals or white goods deliveries – are we in danger of encouraging the genderised view that men are simply ‘muscle’?

Perhaps the most common criticism of the sex trade is that it encourages the trafficking of women, that it facilitates organised crime and exploitation. But people are also being trafficked to do domestic chores or to work in agriculture, yet no one is proposing to tackle this form of modern slavery by stamping on the livelihoods of people who work in those industries.

The fact that the hypocrisy continues, and ironically under the veil of feminism, is frightening to anyone who, like me, believes in individual freedom and equal respect for fellow human beings. Sex workers should not be excluded from that, they deserve our respect, and they most definitely deserve to be listened to.

This doesn’t, of course, mean that we should ignore the issues that drive some women to sex work – we must tackle poverty and women’s lack of opportunities, and in particular the challenges facing single mums. And, yes, let’s tackle sex trafficking. But the way to do all of this is not to stamp on the lives of sex workers. That only makes all of these things worse.

We should always seek to widen women’s options, not close them down. And, at the very least, if you’re going to do the latter, admit that it is on the basis of your own moralism – of what you would or would not want for your own body. Don’t try to hide under the veil of feminism. No one who honestly believes in the feminist phrase “my body my choice” should be ignoring the most marginalised and stigmatised group of working women in our society.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe