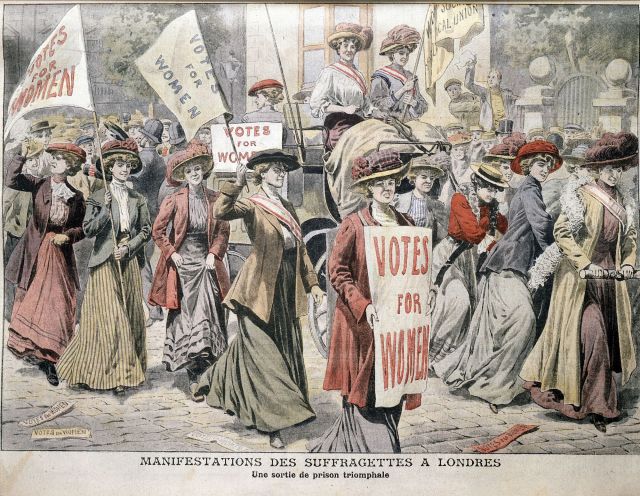

One hundred years after women in the UK first received the right to vote, feminism seems to be forgetting the principles that first set it on course.

Mary Wollstonecraft, arguably the author of feminism, set these principles out in the 18th century, as she dedicated A Vindication of the Rights of Woman to the former Bishop of Autun:

“Consider, I address you as a legislator, whether, when men contend for their freedom, and to be allowed to judge for themselves respecting their own happiness, it be not inconsistent and unjust to subjugate women, even though you firmly believe that you are acting in the manner best calculated to promote their happiness? Who made man the exclusive judge, if woman partake with him the gift of reason?”[1. ‘A Vindication of the Rights of Woman‘, Mary Wollstonecraft, 1972, page 103]

In making the case for equal rights, Wollstonecraft draws directly upon both reason and self-interest. She argues that women are capable of thinking for themselves and should, therefore, be able to make their own decisions, rather than being under someone else’s thumb.

For centuries, the masses – and not only women – had been unable to pursue their own self-interest, as selfishness was seen as “evil” and “disorderly”. Showing that this was not the case was, of course, how big thinkers such as Adam Smith and J.S. Mill transformed political economy, pushing the state and religion out of the way, freeing individuals to be themselves. Wollstonecraft was doing the same.

But despite its liberal roots, feminism today is making two mistakes. It too often embodies the centuries-old “we know best” attitude that Wollstonecraft was kicking against, as well as a more modern “you’re bad for the sisterhood” which she would have abhorred. That’s no more the case than when it comes to women who make money from their bodies: sex workers, Page 3 girls, female hostesses and grid girls.

While making money from your brain is to be celebrated, making money from your body is not, apparently. Modern-day feminism is looking more and more like a group of “clever” women ganging up to pull the rug from under the feet of other women. Women who monetise their brains are denying other women the ability to monetise their bodies. It’s elitist, unfair and hypocritical.

The justification for their approach is two-fold.

Firstly, these neo-feminists claim women have been “socialised” to want to objectify themselves and so do not know what they are doing. In a different – more equal – world, they would not “choose” to reveal their bodies and parade around in high heels, and so, for their own good, should be denied the opportunity to do so in the real world. Perhaps they assume that their entreaties will, given time, generate an epiphany moment. These women, no longer able to make a living, will be grateful and start training to become accountants, politicians and lawyers instead.

I have been the subject of this “we know best” attitude myself. Last year, when giving a public lecture at a new research forum in London on the subject of society in the 1960s and how far we have come since, I chose to walk on stage and address the audience in a cutting edge piece of feminist fashion by the designer Jenna Young.

It was a sheer black bodysuit which I wore to provoke questions about women’s bodies. I thought it would be an interesting test of how far society had come in terms of women having freedom to do whatever they want with their own bodies – thereby fitting neatly with the theme of my lecture.

Not long afterwards, I noticed that the accompanying lecture delivered at the same event by a well-known and well-respected male colleague, who wore his usual suit, had been made available online. Mine had not. I was later told that a couple of attendees believed I was objectifying myself. They claimed to be feminists. My voice was, as a result, wiped from the face of history.

This reflects the attitude of many present day feminists: that whatever an individual woman chooses to do is irrelevant. She is deemed not to know her own mind; not to know what is best for her. Whether I think I am objectifying myself is beside the point; what matters is what someone else thinks – and their thoughts are enough to constrain my freedom.

The other justification given for denying individual women the right to do what they want with their own lives – and their own bodies – is that their choice has negative consequences on the rest of the sisterhood. If you choose to monetise your body – or, simply, to go about your daily business in an outfit that is perceived to be “too revealing” – that choice causes men to look at all other women in a particular way. Essentially, they are saying that the objectification of women is women’s own fault and the only way to stop it is for women to keep their “sisters” in line (needless to say that I disagree).

As we mark 100 years of having a voice, perhaps it is time for feminism to think about where it came from and embrace again individual freedom for all women – not just for the “clever” ones.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe