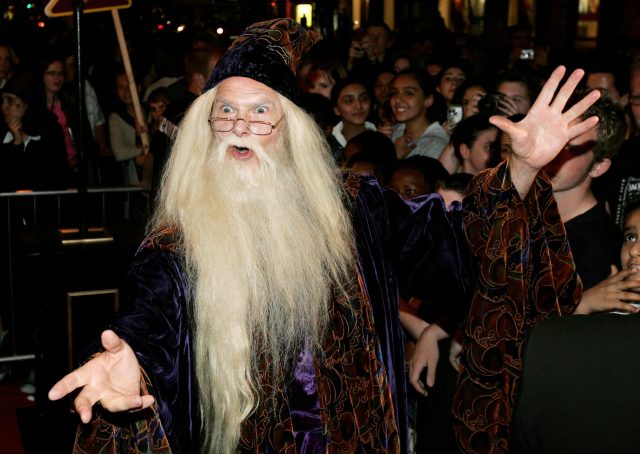

Credit: Gareth Cattermole / Getty Images

“Sister dearest, you and all the gods and your sweet self will surely testify how much against my will I arm myself with this dark technology of magic.”

Virgil, Aeneid.

Magic is a belief in short cuts. Whether it is turning lead into gold, making beautiful women fall in love with you, or transforming lepers into Olympic athletes, magic promises an instant route to where we want to go – quick as a flash, abracadabra. This fantasy of the philosopher’s stone appeals just as much today as it ever has, perhaps even more so.

That magical thinking persists in an age of science is not so much that people continue to be inexplicably stupid and superstitious, refusing to understand and accept the success of the scientific revolution; but rather that they continue to be, as humans always have been, wishful – a word that describes a point on the spectrum that slides dangerously between hopeful and deluded. At its core, a belief in magic is a belief in quick power. This is why magic is a ‘dark technology’. That is why magic is widely seen as dangerous.

In Marlow’s play, the ageing academic Dr Faustus – frustrated with conventional wisdom – summons a dark power in order to extend his life. He renounces his baptism and makes a deal with the devil. He has found a short cut. But this short cut is ultimately disastrous.

If Marlow were writing Faustus today he might make the hubristic academic someone like Ray Kurzweil, the director of engineering at Google. Kurzweil promises that the accelerating power of technology will one day conquer death itself. The day is coming, this modern-day necromancer insists, when we will be able to upload our core being into some cloud of software and live forever. We don’t think of this as magic because we have been persuaded that science is the very opposite of magic.

This assumption seems patently obvious to people. As the sociologist Max Weber claimed, the modern, scientific world-view is one in which:

“…no mysterious forces are in play, eluding calculation, and that our calculations can (in theory) master everything… We need no longer to rely on magic as a device for mastering spirits or pleading with them – unlike the savages for whom such forces used to exist. Calculation and technical equipment do the job.”

It is a telling passage, for while it imagines magic as being overthrown by “calculation and technology” it also accepts that they “do the [same] job”. That is why the futurist and science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke was correct when he claimed: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”

To be fair, the persistence of magic in an age of science has nothing to do with proper science or proper technology. Rather, it has to do with our over-inflated expectations of their power. Most of us non-scientists now rely on things for our everyday existence that we do not begin to understand. When we text our friends, surf the web, take a flight, or even turn on a light switch.

Some of us have a sketchy idea how these things work. But for most of us muggles, we rely on that which is beyond our understanding. And so we get used to the idea that there are forces beyond our ken that have this massive power to fix things. We end up trusting in the (to us) mysterious to solve our problems. We don’t know how it works but we believe it anyway. We end up believing in magic.

Perhaps the most dangerous form of magical thinking today comes when it is claimed that technology will be able to sort out the existential crisis of climate change. As scientists agree, the world has warmed up by 1.5 degrees since the advent of the Industrial Revolution, that coalition of technological ‘advance’ and international capitalism. The magical thinking of technology is that we can continue to dig for coal, fly on planes, eat meat; that we can continue to go on living beyond our environmental means, and that it doesn’t really matter because, one day, someone will come up with some (magical) technological fix. This is wishful thinking.

Our culture has surrendered unquestioningly to the power and promise of technology. It has become the omnipresent grid by which we chart our way in the world – chips with everything – offering us salvation from the threat of the unknown. Through technology we imagine ourselves to be masters of the universe. And that we are more advanced than those Weber called the “savages” that went before us. Technology flatters us with the fantasy of our specialness. We are now a super species, approaching the power of the gods themselves.

Forget Harry Potter. The place where that magical thinking is flourishing today is within the world of technology. The lead magicians of our times are fêted as public figures. They work in NASA and Apple and Tesla. Elon Musk imagines we can evade human extinction by founding a colony on Mars. Post-humanists imagine Homo sapiens evolving into some entirely new species; stronger, faster, longer-lasting.

Algorithms curate our reality, determining our online experience, knowing us better than we know ourselves. Technology in agriculture will provide more food for the needy. Artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence, promising potentially limitless solutions to the human condition. DNA wizardry imagines it can create life itself in a petri dish. “Thy kingdom come,” we all intone. As with magic, we are mastering the unknown. There is no need for us to be afraid of the dark any more. Technology is the new sacred, the new salvation. All hail!

Technology, once a means to an end, has now become an end in itself, and an object of worship. And woe betide those who question this new realm of the sacred, for they will be met with the same angry reaction as those, throughout history, who have dared to question the gods: “All criticism of it brings down impassioned, outraged, and excessive reactions,” as the great Jacques Ellul wrote in The Technological Society.

Why is magic so dangerous? Because it refuses to accept the existence of limits. Faustus is a morality tale about a man who transgressed the limits of what it is to be human. Likewise, climate change is turning into a morality tale about a planet that has transgressed the limits of sustainability. Both are tales of human hubris: and with climate change we have become like Icarus, flying too close to the sun.

Real science rightly pushes against the boundaries of human ignorance. But there are certain boundaries that it cannot wipe away because they are the constituent conditions of what it is to be a human being. The boundaries Faustus perceived to be a limit were, in fact, the defining features of what it is to be human. Think of it a bit like this: Faustus pushed over the walls of his existence, thinking they imprisoned him, not appreciating they sustained the roof over his head. This is how magic destroys us. And why, for centuries, people have been afraid of it. Remember: some things are just too good to be true.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe