Credit: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

So far this year, 62 people have been killed in London following a surge in knife crime. This is not a one-off spike, but an epidemic fueled by gangs and domestic violence.

Politicians have lined up to denounce the violence and come up with ways of tackling it – the Home Secretary set up a Serious Violence Taskforce, while the Mayor of London gave the police greater stop and search powers.

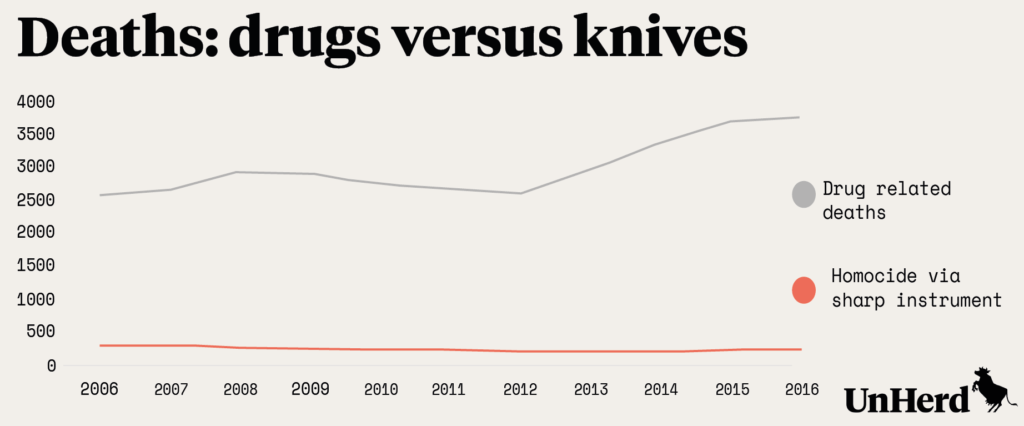

Regardless of whether these measures are enough, their introduction shows that people care enough to intervene. Which makes it all the more disturbing that something which is killing 17-times more people is being all but ignored – the drug epidemic. The UK has become the drug death capital of Europe.

Every day, 10 people are dying a drug-related death, a 44% increase in just four years. Drug deaths are now the highest level since records began. A third of European drug overdoses happen in the UK. Why aren’t we more shocked?

While the drug epidemic has claimed more than 30,000 lives in a decade, deaths are only half the story. Drug addiction devastates families. Stephen, a recovering addict from one of the CSJ’s addiction charities, told me:

“It had a huge effect on my family, the emotional and psychological effect on them was constant, they were always worrying they were going to get a phone call saying that I was dead.”

Fortunately, Stephen’s family never got that call.

And the impact extends beyond an addict’s immediate family. Heroin and crack cocaine users commit 45% of all acquisitive crime, and addiction is one of the driving forces behind the knife crime gripping the UK’s major cities – not that you’d know from the media coverage.

The government can address this by clamping down on supply and giving addicts a way out by investing in treatment.

On supply, we would do well to learn lessons from across the pond. Despite the growing calls for legalisation, America shows just how bad an idea that is.

By legalising cannabis, American states have opened the floodgates to addiction. A tenth of everyone who tries cannabis becomes addicted to it and they have created an aggressive industry which is increasing consumption by 10% a year. It is also worth remembering that America’s current opioid epidemic has been created by over-prescribing legal opiates – powerful prescription painkillers that have proved a gateway drug to heroin for many.

In tackling demand, attention should be focused on opiate addicts, who are the most likely to die. The UK may not have reached the staggering level of deaths seen in the US – America recorded almost 64,000 overdose deaths in 2016 – but opiates still accounted for more than half (2,038) of UK drug deaths in 2016.

The typical victim is in their early 40s, living in the North of England and first encountered heroin during the epidemic of the late 1980s. Blackpool has been particularly blighted, with one in 5,000 residents dying of a drug-related death each year. Job losses hit this community hard in the 1960s as cheap air travel took people abroad for their holidays. It stripped Blackpool of its jobs, and now – like in the struggling communities of flyover America – far too many who lost their jobs are losing their lives.

It is too late to prevent this group from becoming hooked on drugs; but it is not too late to invest in helping them turn their lives around. Unfortunately, the government has been doing the exact opposite. Six years ago, the government removed the ring-fence from a £500 million treatment grant.

The treatment sector has buckled, with record closures of treatment facilities across the UK. In particular, in the North of England, leaving those who need the most help with the least support.

To make matters worse, money is now increasingly being spent on the cheapest option – parking people on substitute drugs, such as methadone, rather than actually investing in changing people’s lives.

We have reached crisis point. Approaching half of high-risk opioid addicts are not in treatment, and of those that are, the quality is so low that less than 7% are successfully completing their treatment.

This is a burning injustice. One that continues to take thousands of lives; continues to fuel violence and destruction on our streets; continues to destroy families. Yet it is a problem that can be fixed, if our politicians and pundits cared enough.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe