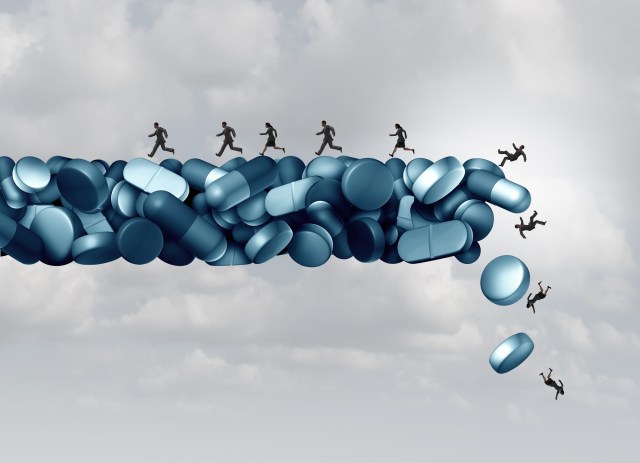

Credit: Getty

We need a phrase for a negative ‘wonder of the world’ – by which I mean a unique ‘achievement’ that compels our attention for all the wrong reasons. A ‘horror of the world’, perhaps.

However we might describe it, America’s opioid epidemic certainly qualifies as a prime example. In a must-read briefing for the New York Times, Josh Katz sets out the latest situation:

“Drug overdoses are the leading cause of death for Americans under 50, and deaths are rising faster than ever, primarily because of opioids.

“Overdoses killed more people last year than guns or car accidents, and are doing so at a pace faster than the HIV epidemic at its peak. In 2015, roughly 2 percent of deaths — one in 50 — in the United States were drug-related.

“Overdoses are merely the most visible and easily counted symptom of the problem. Over two million Americans are estimated to have a problem with opioids. According to the latest survey data, over 97 million people took prescription painkillers in 2015; of these, 12 million did so without being directed by a doctor.”

How did this disaster happen? Ian Birrell, who writes powerfully on this issue for UnHerd, apportions much of the blame to the decades-long massive over-prescription of (legal) opioids. However, he also condemns the failed war on (illegal) drugs and calls for decriminalisation – “as with any market that has potential to cause death, there should be state control and regulation.”

To my mind, there’s a contradiction here. The legal market in opioids that Birrell rightly condemns as “capitalism at its least ethical” is nevertheless a regulated market. Therefore if the war on illegal drugs has “failed” then so has the attempt to regulate a legal supply. Yet we are exhorted to abandon the former, but double-down on the latter.

In theory, it’s better to have the drug supply controlled by licensed professionals than by criminals. This, of course, assumes that a regulated market would displace the illegal trade. However, the American experience with opioids shows that the displacement effect is far from guaranteed – quite the opposite, in fact.

More from the New York Times:

“…Newly decentralized drug distribution networks pushed heroin and counterfeit pharmaceuticals into suburban and rural areas where they had never been. Everywhere the suppliers went, they found a ready and willing customer base, primed for addiction by decades of prescription opiate use.”

It’s almost as if by normalising the use of a harmful product, big business and big government creates a much bigger market for it – one which big crime is all too willing to supply.

Markets encourage innovation and this one is no exception. Opioids don’t just include opiates (i.e. drugs derived from opium); the term also covers substances that are synthesised to have the same effect – often to a greater degree. The most notorious of these synthetic opioids is fentanyl – which is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

With a more concentrated and less traceable product, the illegal trade and its impact has been transformed. The New York Times again:

“In 2000, the most common age for drug deaths, including those not involving opioids, was around 40. This was the generation that first grew addicted to prescription opioids in large numbers — white people especially so. Now there’s evidence that the opioid epidemic is dividing into two waves, with a new group of younger drug users growing addicted to, and dying from, heroin or fentanyl rather than prescription pills.”

So there you have it: the legal, regulated distribution of narcotics creates new opportunities for the criminal trade; and less harmful products are joined or replaced by more harmful products.

This is the practice, not the theory. It wasn’t meant to happen, but it has.

It turns out that making an extremely addictive range of poisons widely available can have unintended consequences.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe