Prime Minister Theresa May chats with first-time buyer Laura Paine during a visit to new housing development in Berkshire. Credit: Leon Neal/PA Wire/PA Images

“Capitalism needs neither propaganda nor apostles – its achievements speak for themselves”.1

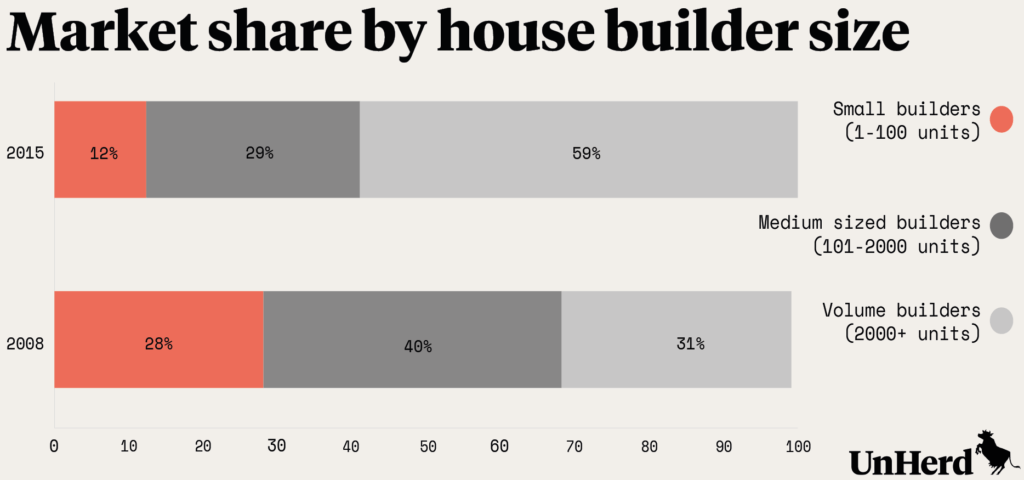

Residential construction is rigged heavily in favour of large developers at the expense of homebuyers. Homes in the UK are built mostly by large “volume” builders operating on a speculative basis – with developers or land agents buying up acreage years before building starts. And this market distortion has become far worse since the 2008 financial crisis, as the industry has become increasingly concentrated.

Strong demand should mean developers build more homes and sell at a competitive price. But the low availability of suitable land leads to speculative bidding by developers – who then maintain big profit margins despite soaring land costs by building units that are small, low-quality and over-priced.2

High-cost land is also a barrier to small- and medium-sized SME builders, who struggle to raise up-front finance. This lack of competition, in turn, means land agents and large developers assemble sizeable land-banks, exerting control over the number of homes coming to market – often sitting on sites to reap additional gains as the shortage keeps prices rising.

This status quo can only be disrupted if land is available at steady, reasonable prices, with new homes then competing on quality and price. The Government must, therefore, become much more involved in the land market, offering more state acreage, with local authorities using more compulsory purchase orders (CPOs).

Some may balk at this. Surely, free markets produce the best outcomes? The UK house-building “market”, though, is barely a market.

“Land planned for major development should be bought well in advance by a public authority for disposal to private enterprise or to public enterprise as required,” said then housing minister, Keith Joseph, in 1963. Few would describe Margaret Thatcher’s future economics guru as an enemy of free markets.

Today, the public sector owns around 6% of all freehold land – almost a million hectares – rising to 15% in urban areas, including countless sites ripe for redevelopment.3

Yet, sales of public land for residential development have been hopelessly low. In a recent report, NHS Digital identified 1,332 hectares of surplus land across over 550 sites, just 91 hectares of which had previously been sold.4 The Government must cut through Whitehall torpor and significantly ramp up sales for residential development from its own land holdings.

Volume house-builders should be excluded from some of the sales, and non-building land agents should always be excluded. The most attractive small plots, particularly in city centres, should be reserved for SMEs – which, in need of cash flow, build quickly. With certain buyers not permitted to bid, state land – sold via competitive tender or auction – may sometimes fetch “sub-market” prices. Treasury dogma that this is unacceptable must be fiercely resisted. Getting local housing supply moving stimulates growth and tax revenues.

State land sold to all builders, large or small, should come with “permission in principle” status.5 To ensure speedy building, once “technical details consent” is granted, homes must be completed within two years as a condition of sale, or ownership reverts to the state. In localities where more rapid development is needed, state land should be sold with “pink zone” status. This designates broad permitted building parameters, with decisions on planning specifics guaranteed within two months.6

In addition, local authorities and city administrations should create powerful Housing Development Corporations (HDCs) that acquire land, then sell it on to developers once outline planning permission has been granted, again with time limits on completions.7 Variations on this model are successfully used in Germany, Holland, Singapore and South Korea.

When planning permission is granted, converting arable land to residential use, the entire valuation uplift – the “planning gain” – currently accrues to landowners and agents. With prices sometimes rising a hundred-fold or more, this results in multi-million pound windfalls. Yet land is a public good – and while it can be privately owned, how it is used is of legitimate interest to everyone. And vast planning gains now going to owners and agents. CPOs should be therefore be used more widely, but at a price reflecting “existing use” – say farming – plus negotiable compensation.

If an HDC sells land – primarily to SMEs – having captured the planning gain, the price at which it is sold to developers could be set high enough to ensure sufficient funding for local infrastructure and social housing (but lower than elevated open market valuations).

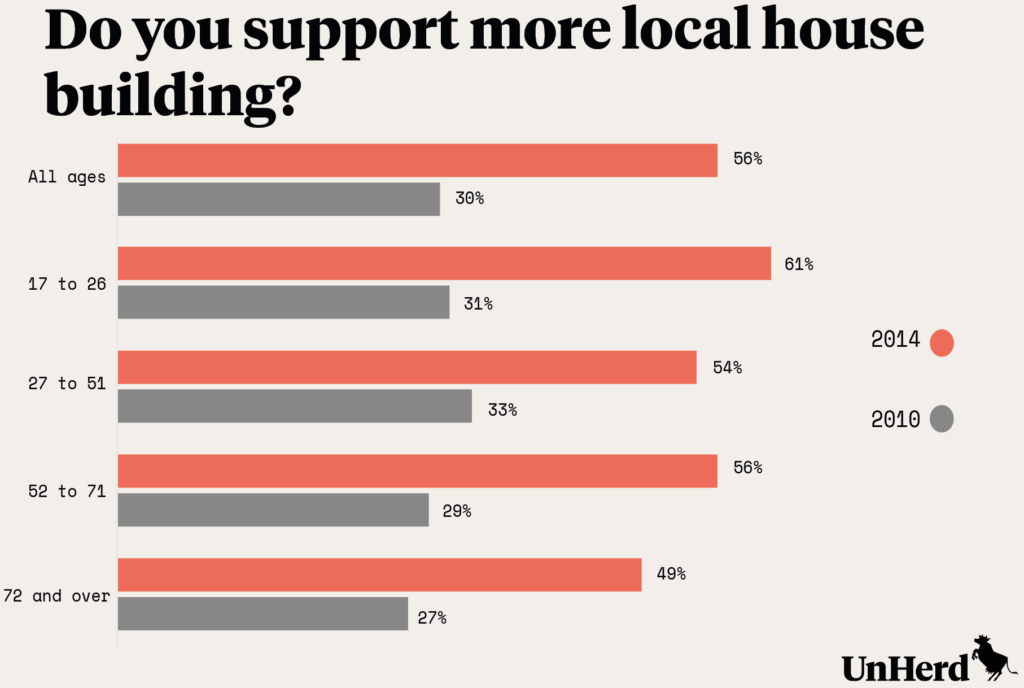

As the housing affordability crisis worsens, public support for more house building is growing – up from 30% in 2010 to 56% in 2014, as shown in the graph above. If HDCs were used widely, keeping “planning gain” at the local level, these funds could be ring-fenced for new schools, hospitals, leisure facilities and even temporary reductions in council tax. HDCs, and the local public benefits they can bring, could boost further the trend of rising local support for more development.

During the 1930s, over 300,000 homes a year were built – many in huge “metroland” London suburbs such as Brent, Harrow and Barnet. They were constructed, for the most part, by local SMEs, building for both local councils and private buyers. When the UK last consistently built over 250,000 homes a year, SMEs accounted for two-thirds of them.8

Many SMEs were wiped out during the 2008 financial crisis. Those left can barely compete with the volume developers that now dominate UK house building. Struggling to raise finance and secure residential plots, SME developers have, quite literally, lost considerable ground.

As the graph above shows, since 2008 the house-building industry has become much more concentrated. The market share of large developers has practically doubled, to almost 60%. Within that SME total, small developers building under 100 units per annum have suffered most. Such firms – typically family-owned and favoring fast build-out – built 28% of new homes in 2008, but just 12% by 2015. Our house-building sector “has all the characteristics of an oligopoly”. says the House of Lords.9

In 2008, an Office of Fair Trading study into the UK house building industry found “little evidence” that market concentration was hindering the delivery of new homes.10 But they did warn that “many of the mergers creating larger firms have been in part motivated by a desire to obtain land”. That was ten years ago, and since then the market share of the volume developers has almost doubled.

The OFT also criticised the patchy nature of the UK’s public land records in 2008. This makes it tough to assess whether land banking is restricting competition – a failure now more important given rapid recent consolidation.

The “Letwin Review” into increasing delays between planning permissions being granted and new homes being completed is due to report this autumn. Since 2013, “build out” times between full planning permission and completions have soared from 1.7 years to 4 years. The rapid industry consolidation provides compelling circumstantial evidence of restrictive practices – certainly enough to warrant open and detailed investigation. Given the public interest issues at stake, a behind-closed-doors “review” of this vital industry is not enough.

Since the last OFT investigation a decade ago, UK house building has consolidated at an unprecedented pace, the market share of the largest players almost doubling. It is entirely reasonable the OFT’s successor has another look.

Almost 40% of residential planning permissions now lapse. Big developers should “do their duty and build the homes our country needs”, said Theresa May last month.11 Yet the “duty” of stock-market-listed developers – their legal obligation, in fact – is to maximise profit within the law. So the law must change, placing financial sanctions for delays both in applying for planning permission and subsequent build-out.

Developers’ land should attract a levy, payable to local authorities, while it remains undeveloped – similar to a classic “Land Value Tax”. Having bought land, LVT should apply after a year unless the developer has submitted a reasonable planning request. Relatively low at first, the LVT should rise each year permission isn’t sought. Revenue raised should be partly used to staff local planning departments, encouraging faster and better-quality decision-making.

Once planning permission is granted, developers then own a far more valuable asset, which also generates a huge opportunity cost to society if unused – so the LVT should be much higher. After a grace period to allow normal build-out – say, two years – a punitive LVT should apply if homes granted planning permissions are not physically completed and available for sale. This post-planning levy should escalate each year build-out remains incomplete, giving developers a stiff monetary incentive to deliver homes.

LVT-type charges on landbanks with and without planning permission should initially apply only in designated “high-demand” localities – where affordability issues are most acute. Such designations could be awarded by Homes England, the newly constituted government agency, as part of a broader revamp of the UK’s Land Registry –which is not fit for purpose. Homes England should also regularly publish, at a regional and national level, achieved “build-out speeds” of various developers.

Local authorities must also use CPOs, if needed, to force development on stalled sites. Owning a site with planning permission means a rival builder cannot build there. CPOs in this context are a last resort but the threat must be real. Developers must understand that valuable planning permissions, as well as a right to build, are also an obligation to do so.

To really boost house building, specific assistance should be given to the smallest SMEs – those building under 100 units a year – in accessing finance and dealing with the planning system. With faster build-out now vital, Treasury guarantees for approved SMEs are needed, particularly those undertaking schemes involving considerable affordable housing.

Rather than “Help-to-Buy”, the benefits of which largely accrued to volume developers, we need a sustained, multi-billion pound “Help-to-Build” scheme – with the Government standing behind the borrowings of a limited number of selected SMEs.

For smaller SMEs, Section 106 obligations that can require payment towards local infrastructure, should be dropped, with such firms paying only the flat-rate Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL). For an initial ten-year period, SME-built developments of under 20 units not benefiting from Help-to-Build finance should be free of affordable housing requirements.

The UK’s 25 million homes cover just 1.1% of this country’s landmass. Commercial buildings account for another 0.65%, with roads and rail taking up 2.2%.12 Only around 4% of English land is actually built on, with another 3% covered by water. Over 90% is “space”.

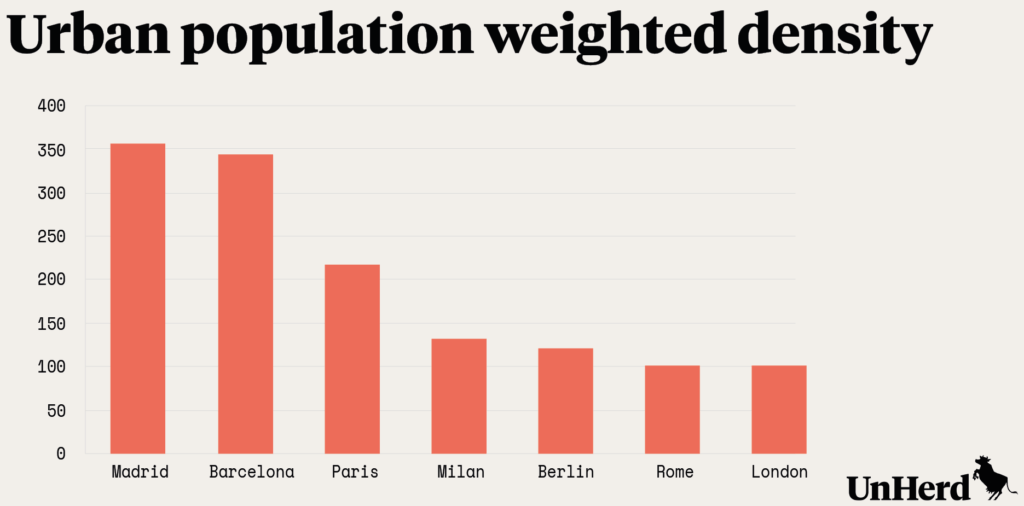

Britain’s housing stock could rise by a fifth – another five million homes – using only another 0.2% of our landmass. If we increase building density by developing more apartments, particularly in big cities, the amount of land needed would be even less. As the graph above shows, urban building density across Britain is low.13

Some of the UK is, of course, mountainous, too remote, ecologically sensitive or of stunning natural beauty. Yet Britain is still blessed with many, many acres of barely-used land within easy commuting distance of towns and cities. The green belt covers 13% of England’s total acreage, but despite the name, some of it is urban scrubland.

Rather than treating such boundaries as untouchable, we need locally-led green belt reviews, facilitating sustainable, well-designed homes close to transport, while preserving accessible green spaces. Some green belt could be “moved” – recognising that our big cities have become far more populous since these areas were designated in the 1950s.

Introducing HDCs could generate local debate about shifting these boundaries. The prospect of land sale revenues feeding into local schools, hospitals and other amenities could transform such debates, with property values being enhanced rather than harmed by development.

One way to limit the use of green belt, and other sensitive sites on the edges of existing villages, is to build more “new towns”. While 14 new towns were designated in the 1960s, almost no sizable additional town has been created since, despite rapid population growth. If state land is designated for such developments, parceled up and sold to competing developers, including many SMEs, large plots could be built-out quickly. And again, funds from HDC-captured “planning gain” could finance affordable housing, infrastructure and common areas on such sites.

Tackling the UK’s chronic housing shortage requires a multi-faceted response. Since 2010, the Government has focused on “demand side” measures – injecting taxpayer cash into a property market already tight due to long-standing demand-supply imbalances. By pushing up prices further, this has done more harm than good.

But there are some demand-side measures that would be helpful. There is surely scope to reduce and ultimately abolish stamp duty on property purchases. This would spark more housing transactions, boosting turnover in the secondary market and thereby encouraging the more efficient use of the UK’s housing stock.

Another useful demand-side reform would be limitations on the now very significant purchase of new homes for investment by overseas buyers. This has spread beyond Central London to its suburbs and on to Manchester, Cambridge, and elsewhere. Investors from China, India and the Gulf are buying thousands of units each year, reflecting not only faith in the UK legal system, but a shrewd assessment our property shortage is so endemic, and the vested interest ranged against change so entrenched, that prices will continue to spiral.14

Home Truths has focused on private sector provision and the crony capitalist drivers of the housing shortage. That is because commercial house builders are central to the UK’s housing supply. They should account for the bulk of new-build homes and incentivising them to deliver good-quality, keenly-priced products in sufficient numbers is the key to solving our housing crisis.

But a mixed-economy of housing provision is vital, not least when it comes to providing the social housing that will always be needed for those on low-incomes or otherwise unable to buy or rent their own home. There is much scope to be innovative in this provision.

Large developers could be offered state-owned land with planning permission at relatively low cost, on condition it is used to build, within a certain time, primarily social housing. That could generate a return for developers in the form of regulated but steady rental payments.

Part of the UK’s considerable pension fund wealth, constantly looking for consistent yield to match long-term liabilities, could also finance social housing – given a combination of political will and regulatory acumen. Such steps could significantly enhance our social housing stock.

The roots of this UK housing shortage stretch back decades. House building has been way below requirements under successive governments – and tackling what is now an acute crisis will take political courage. But the alternative is a divided nation, with an ever-widening gap between the property haves and have-nots.

“Capitalism delivers the goods”, wrote the economist Ludwig Von Mises, some 70 years ago. Yet UK voters increasingly think otherwise – that’s in large part due to a cruelly dysfunctional market for housing.

Read the full Home Truths series here.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe