Credit: Lalocracio / Getty Images

Capitalism is a on a knife-edge. In Britain just 17% of people think capitalism is “working well”. Over the pond, in America, more millennials would rather live in a socialist country than a capitalist one. And Polling for UnHerd last summer found that in both nations around 60% of people believe capitalism makes the poor poorer and the rich richer. This disillusionment is driving support for hard-left parties.

Some ardent defenders of capitalism rail against the “stupidity” of voting for politicians who advocate economic policies that have been tried and found wanting. They see as irrational the rejection of a model that has transformed the standard of living of billions of people across the globe. But they are the fools, because in ignoring the lived reality of millions of people in advanced capitalist economies, their attitude will spell the downfall of the very model they seek to protect.

For last summer’s poll findings are far from irrational. Living standards have been stagnating, along with wages, for decades. Job security has been eroding. Social mobility stalling. Inequality growing. These facts are irrefutable – in the UK and America, the rich are indeed getting richer as everyone else gets relatively poorer. While the great engine of prosperity may be running smoothly for developing nations, in the West it’s barely stuttering.

But if the first step in solving a problem is recognising there is one, then maybe we’re about to set off on the road to recovery. For while the extremes of Left and Right may not understand the value of reforming capitalism, there is a growing consensus among those in the middle that a reboot is needed. That capitalism is the right model, just not in its current – corrupted – form.

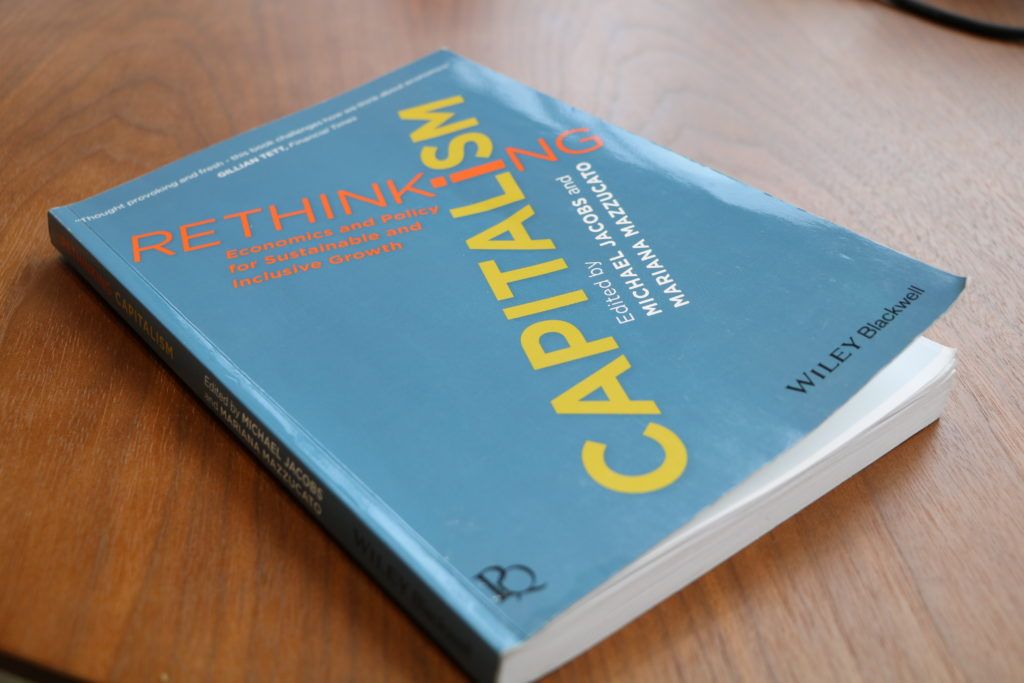

This was the subject of my podcast discussion with Michael Jacobs, co-editor of the 2016 book Rethinking capitalism: economics and policy for sustainable and inclusive growth.

Rethinking capitalism is a critique of economic orthodoxies – exposing, via a series of essays by eminent academics and economists, the flawed thinking that has led to our current broken model. As Jacobs and Mariana Mazzucato point out in their introduction:

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe