Steep staircase inside tenement building in the East Village, New York City. Getty.

The first in UnHerd’s new series – spotlighting art that describe the nature of poverty as it exists today.

In recent years a number of academics have focused their attention on what in the US is called ‘flyover country’ but which in the smaller UK is probably best translated as ‘the places that time forgot’[1. The Times columnist, Matthew Parris, was criticised for using ‘Hopeless’ as a synonym for Clacton-on-Sea, with its shell-suits and air of death, though to be fair to him, as a young MP Parris made a memorable documentary while vainly trying to live in Newcastle on £27 benefits per week. More.]. There is a faint sense of the visiting anthropologist about many of these endeavours, though the best – Arlie Hochschild’s Strangers In Their Own Land for example – do imaginatively convey the mixture of despair and resentment of struggling folk without turning them into secular saints.

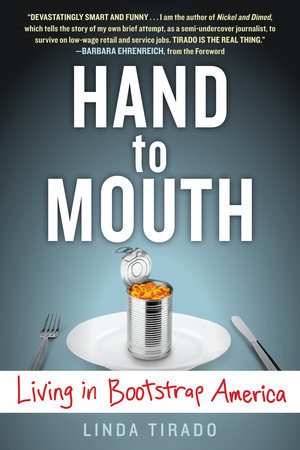

What one misses is a first person voice describing the lived experience in all its precarious complexities, rather than an outsider sampling it for a short while. For that I would recommend Linda Tirado’s Hand To Mouth, which was published in 2014.

What one misses is a first person voice describing the lived experience in all its precarious complexities, rather than an outsider sampling it for a short while. For that I would recommend Linda Tirado’s Hand To Mouth, which was published in 2014.

The subtitle of one of its editions, ‘The Truth Of Being Poor in a Wealthy World’ captures what is most original in Tirado’s work – since the book is also a moral mirror for those who don’t even have to think about the daily choices they make. The book appropriately concludes with an ‘open letter to rich people’ about sensitivity to the realities of being poor. Read it if you do not bother to talk to checkout women (it’s usually women) or waiters – or perhaps if you are more comfortable with robots and machines?

Tirado’s book had a very contemporary genesis. One night, after attending early morning college classes prior to working at her two low-paid jobs, Tirado (who has two small children) read a post on an online message board asking: “why do poor people do things which seem so self-destructive?” Her mini essay-length response went viral and she received 20,000 emails in a week. The essay was reproduced by the Huffington Post and Nation, and before long she was asked to turn it into this book.

Tirado simply sketched a working day which began at 6am and finished after midnight the following morning. Although by 2013 she and her husband Martin were relatively comfortable, Tirado had vivid memories of living in a motel on a diet of peanut butter and frozen burritos, because cooking food would attract cockroaches. Better to smoke cigarettes to suppress her appetite than to have to suppress crawling insects. Don’t eat in public either for fear of being unable to smile without embarrassment. Tirado lost several teeth after a drunk driver smashed into her car, and when a dental plate was inserted, it soon broke. There are no photos of her from that period (2006) onwards, because of an obvious problem when any photographer said ‘Smile!’

“Nobody gives enough thought to depression. You have to understand that we know that we will never not feel tired. We will never feel hopeful. We will never get a vacation. Ever. We know that that the very act of being poor guarantees that we will never not be poor”.

Most of what Tirado writes about dead-end temporary jobs is pretty familiar, notably the petty chicanery of corporate employers determined to squeeze the maximum profit from an exhausted workforce. She is also good on life without any financial cushion, particularly if a car breaks down or is towed away, and why very poor people resort to predatory lenders, about whom her views are ambivalent when compared with her detestation of banks.

Where her book breaks new ground is on the personality deformation this way of being induces, of becoming like an armoured ‘zombie’ which in a vicious circle, the Customer King quickly reads as ‘rudeness’. The endless possibilities of a consumer society mean nothing to someone who has fryer grease in the hair (‘bad hair’ everyday), who knows how to wash her single pair of jeans so they will fit when she is size 12 or 16, but who has nothing to say on social occasions because she has not been to the latest bars, movies or restaurants. All the time the rich are enjoining the poor as to how to behave too, without comprehending what that means. As she writes:

“Responsible poverty is an endless cycle of no. No, you can’t have that. You can’t do that, can’t afford that, can’t eat that, can’t choose that. This is off-limits, and that is not for you, and this over here is meant for different kinds of people. More than once I’ve spent money I couldn’t really afford simply to state that I could, if only to myself. Just to say it”.

Predictably enough, Tirado’s book became caught up in the ideological conflict between Left and Right over the role of government in alleviating poverty and the responsibilities of the individual towards society. The Left eagerly embraced her as an example of how people are structurally trapped in poverty, making forced choices about their lives that cannot warrant individual blame. The Right responded with charges of the Left’s susceptibility to ‘poverty porn’ and began to pick holes in Tirado’s ‘biographical’ account[2. Here’s the Reason website trying to do so in December 2013.]. Some of this was so nasty and petty that it tells you more about the authors than Tirado herself.

Sceptics say that after a conventional upbringing, including a brief stint at the same prep school as the one attended by Mitt Romney, Tirado had left home at sixteen, drifting about in ways that are common to many young people trying to find a road in life. Her one bout of ‘real’ poverty (which she describes on pp. 59-60) came in her late twenties after her husband, a Marine who had served in Iraq, did not receive his veteran’s benefits payment and their basement apartment simultaneously flooded. Her critics say that Tirado’s sense of hopelessness was belied by her early morning college classes, not to mention the $62,000 she crowd-sourced to fund writing of her book. At one point acrimony over Tirado – by then a minor celebrity – reached the point that she had to whip out her dentures on camera to prove the state of her teeth.

Despite these claims that Tirado has perpetuated an elaborate ‘hoax’, Hand to Mouth ranks Number 7 on a list of the all-time best books about poverty, slightly below Dickens and Steinbeck. That must be grim news to those who want to inspect Tirado’s teeth. I am inclined to be generous about Tirado’s book too.

Like the best writers Tirado has a way of animating the apparently ordinary, often by turning it around so we notice something fresh. This more than compensates for a few self-indulgent passages in a book that is completely unsentimental. She explicitly incorporates the responses of the rich to the poor, in other words venturing beyond the well-trodden terrain of who pays for what in the dessicated musings of think-tank folk, even if this means sometimes ‘objectifying’ the well off. The book is admirably direct, cutting through the myriad subtle social evasions that allow these different tribes to coexist.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe