When Antonin Scalia died in early 2016 Barack Obama had the opportunity to replace one of the most conservative members of the nine person US Supreme Court with a liberal. If his nomination of Merrick Garland hadn’t been controversially thwarted by the Republican leader of the US Senate, Mitch McConnell, America’s Supreme Court would have become solidly liberal by a five-to-four votes at minimum and probably by six-to-three. And so here’s my question: did it even cross Barack Obama’s mind that he might have some kind of responsibility to ensure that his country’s ultimate enforcer and interpreter of the founders’ Constitution and of all the laws passed since should ideally command broad support across the US population? I doubt it. Uppermost in his mind would have been the pro-abortion, pro-gun control etc concerns of his own party’s base and their hunger for an anti-Scalia to replace Scalia.

I’m not (for once) making an anti-Obama or anti-Democrat point here. If the position had been reversed and a Republican President had had the opportunity to install a conservative judge likely to overturn Roe Vs Wade or to enhance the Second Amendment rights championed most vociferously by the National Rifle Association, he or she would almost certainly have done so. Anything less than the nomination of a full-throated ‘one-of-us’ would have meant a serious challenge for the party’s re-nomination in the case of a first-term president. And we had proof of the desire for a winner-takes-all politics last week when Donald Trump expressed a desire to scrap the rights of the Senate minority to filibuster the federal budget. Although he didn’t actually win a plurality of votes cast in his contest with Hillary Clinton he clearly wants to take all powers of scrutiny from the representatives of those with different views to his.

We see the desire for total victory in British politics, too.

Two recent examples stand out:

- There’s the case of the former leader of Britain’s Liberal Democrats Tim Farron. It wasn’t enough for this evangelical Christian to accept UK laws on access to abortion and gay equality. Opponents and journalists attempted to make windows into his soul and demanded to know if his faith led nonetheless led him to disapprove of the termination of a pregnancy or of two people of the same sex getting married. Incidentally, a good number of left-leaning parties have elevated the abortion issue into litmus test status. Anyone who opposes abortion rights can’t be a candidate for Canada’s Liberals, for example. That pro-life/antiu-abortion person may be left-leaning, green and Justin-Trudeauesque in all other taxing, regulating etc respects but – even though the country’s abortion laws are under no threat whatsoever – they aren’t welcome in the governing not-s0-‘Liberal’ party (or in Canada’s even more ‘progressive’ NDP).

- After the Tories won Britain’s 2015 general election with 36.9% of the popular vote they proposed slashing (by 19%) the funding enjoyed by opposition parties to hold the government to account. Simultaneously, they proposed a substantially larger taxpayer-funded budget for their own political operations. A few wise Conservatives, who understood the importance of a properly-resourced opposition to functioning law-making, helped to veto the idea (perhaps also fearing that such hyper-partisanship would only invite Labour to take their revenge once they were back in charge).

This demand for total victory is not just evident in politics. A particularly ugly example of the zero tolerance of diverse views in higher education came at the turn of the year when academics at one of the world’s most prestigious universities turned on Professor Nigel Biggar after he had said that the British Empire had been “morally mixed” in its implications. The director of Oxford University’s McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics and Public Life hadn’t in any way minimised the darker elements of what had been committed in the many parts of the world once coloured British imperial pink. He’d simply argued that a fair assessment couldn’t be one-sided. ‘Oh yes it must be’ was the effective shout back from 58 academics – followed by even uglier student voices who accused Professor Biggar of being a “bigot”.

The economic historian Niall Ferguson reflected on absolutism in his interview for UnHerd last year. While globalisation might be in the overall long-term interest of almost everyone on the planet (especially the poorest of the poor) it had produced many casualties amongst the less skilled in the developed world and the Davos crowd might have avoided much of the populist democratic insurgencies of recent times if more time had been given so that welfare and education provision could have kept pace with fast-moving trade and immigration revolutions. But that time wasn’t given. Politicians like Tony Blair gave speeches extolling globalisation and castigating anyone or any group who attempted to raise concerns at the impact of change on the beneficiaries of the old era.

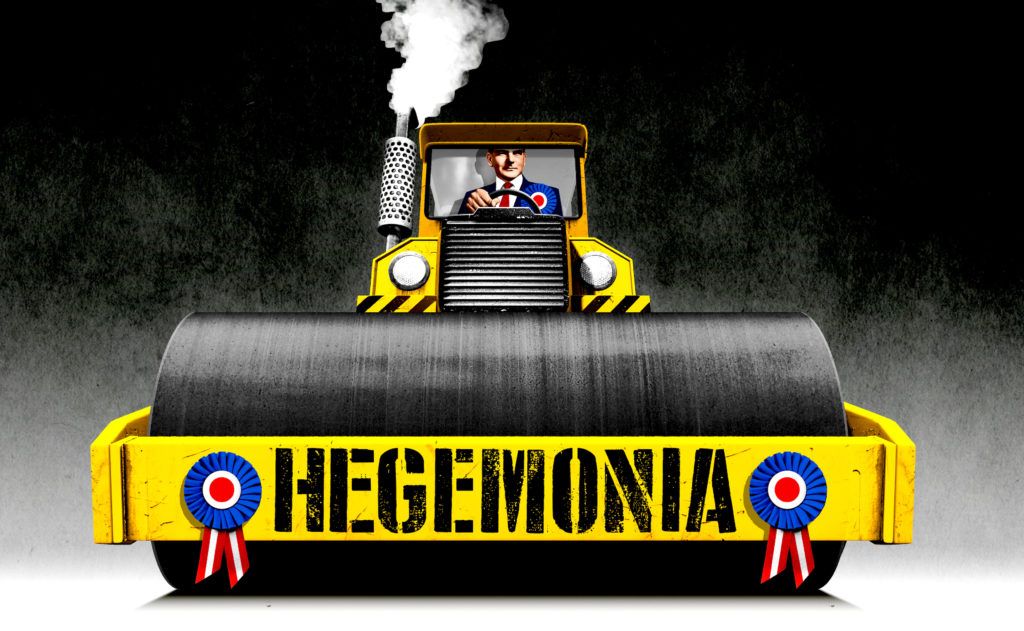

There are many reasons for this hegemonic insistence on total victory and the thirst to not just win office or ascendancy but to flatten and marginalise opponents. There’s the rise of activist classes within political parties and of ‘narrowcast’ media platforms that thrive by playing to narrow ideological or social groups. There’s just rudeness, too. Reflecting on the increasingly sour nature of Britain’s public square, Chris Rumfitt recently noted how…

“Remainers are remoaners who are plotting to subvert the democratic will of the people. Leavers, meanwhile, are xenophobes wanting to turn their back on the world. Tories are “scum” who hate the poor. And Corbynites? They love terrorists while hating Britain.”

And don’t think it’s just tabloids that are guilty of this. Matthew Parris may be softly-spoken, use long words, write (brilliant) columns for The Times and present high-brow programmes for BBC Radio 4 but his characterisation of people with a different view to him can be as ugly as anything produced within much larger circulation titles. Deep down Brexiteers are just racists. Apparently. And the average Tory activist? “Spittle-flecked, obsessively anti-European, immigrant-hating social and [a] cultural reactionary.” He was at it again last Saturday, painting EU referendum opponents in the least flattering possible light.

Can we turn the tide against this problem of hegemonia (or do I mean hegemania?).

Can we recognise that attempting to call any and all opponents racists, fascists and bigots – without good cause – is not just offensive but electorally incendiary? (Hopefully you might have read Paul Embery yesterday).

And can we be patriotic enough to yearn for minorities to feel that their country’s institutions (whether the US Supreme Court or the BBC or universities) are not closed to them?

And can we have the humility to know that victory and vindication are not 100% bedfellows. That political and other opponents who may have lost votes or circulations or professional prestige may still hold useful, insightful opinions and, occasionally, there might be some merit in listening to ‘the defeated’ a bit more carefully – and sometimes changing course as a result.

Let me end with one practical (and even a little sacrificial) implication of my deep worry at the balkanisation of politics being produced by hegemania. No vote in post-war British history has given me more delight or pride than that of the outcome of June 2016’s EU referendum. And I’m pretty convinced that a full implementation of the majority’s desire to leave the EU means we can’t be half-in and half-out. We should be leaving the single market and customs union if we’re to be fully free of the EU octopus – and especially its expansionary, judicially activist courts. But there wasn’t a 66-34 victory on 23rd June 2016 – the victory was 52-48. Nearly two years after the vote (partly because of Theresa May’s failure to deliver change on three key fronts (as I previously set out)) the poison in the national conversation shows no sign of dissipating. For the sake of the temper and popular authority of our national democracy I think it’s time to make a concession or two to the other side and that concession might be continued membership of the customs union. This doesn’t have to be forever. It could be reviewed within five or ten years – when the potential of trade pacts with the fast-growing parts of the non-EU world has (or has not) been established.

More generally – in combatting hegemonia – we need to work harder at understanding opponents.

Is it really sensible to vow never to be friends with parliamentarians from another party?

Are sometimes-annoying filibuster powers enjoyed by minorities really anachronistic or, actually, sensible brakes on what might be rushed thinking?

Should more comment pages be more like those of The (London) Times and less like echo chambers?

I’d love your thoughts. Please use the Have Your Say button at the top of this page to tell me what you think. It’s thoroughly depressing that the populist insurgencies of 2016 (and since – see Italy!) have largely produced deeper trenches rather than bridge-building. Hegemonia isn’t the only explanation for the deepening divisions (I’ll be exploring others in coming days) but it’s an important one.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe