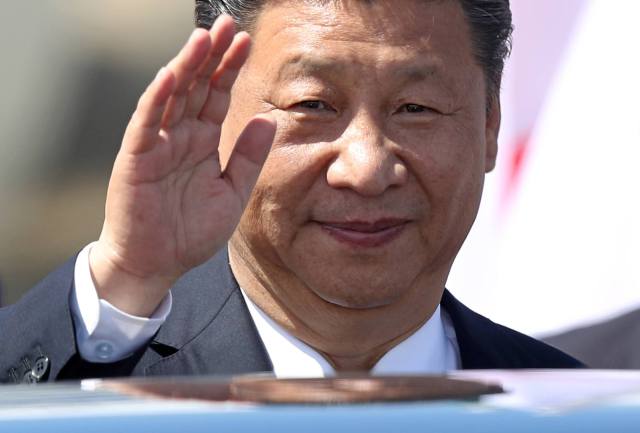

Xi Jinping has too many enemies to give up power safely. (Credit: Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

In December 2014, Xi Jinping closed the trap around Zhou Yongkang, the retired Politburo Standing Committee member who had built and led the most comprehensive internal security system China had ever seen. As he dispensed with ‘the Tiger’, his most powerful opponent, the chances of Xi Jinping voluntarily leaving office sharply declined.

And then, the announcement at the weekend that the two-term rule for the Chinese presidency was scrapped provided a conclusion to the five-year process of power accumulation; it marked a return to politics of leader worship, and the re-assertion of Communist Party dominance in Chinese life.

This move was no surprise to anyone who has followed Xi’s first term in office. When he came to power, in 2012, China was riding high on the prosperity that Deng Xiaoping’s reforms had ushered in 20 years previously. Deng had learned the hard way that excessive concentration of power damaged both Party and country, and had laid out a succession formula which had allowed a peaceful transition twice – an unprecedented advance in China. For the first time, power was passed on without bloodshed.

Consider what had gone before: from 1949 to Mao’s death in 1976, China had been consumed by savage internecine power struggles within the Party that had spilled out into catastrophic nationwide battles. In the years of Maoist supremacy, nobody dared gainsay the leader’s grandiose visions, visions that killed more Chinese in those decades than all the war, pestilence and famine that had marked the first half of China’s grim 20th century.

Deng himself, twice a victim of Mao’s purges, was clear that China should never again suffer under a leader who held absolute power, and understood what was required to avoid it. One important condition was a consensual model of leadership. Another was that a power holder could relinquish his position safe from fear of vengeance. When Xi imprisoned Zhou Yongkang, he removed that guarantee. Now, he himself has too many enemies to give up power safely.

Xi Jinping’s real power bases are his posts of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and head of the Military Commission. When he took over the Party, it was in decline: its ideology was confused, its membership was shrinking and it was publicly reviled as a vehicle for corruption and rent seeking. Political reform was widely expected and openly demanded, as people hoped for a continuation of Deng’s prescription of strengthening the state and the rule of law as a defence against Party abuse.

But Xi Jinping has undermined or bypassed the institutions of the state, concentrating executive power in “leading small groups”, many of which he chairs. He has reinserted the Party into every aspect of national life – from the education system to private enterprise, shutting down the think tanks, locking up the lawyers and others who were freely debating China’s constitutional future.

He has imposed a new ideology that promises to make China great again, in an obvious echo of another global leader. And he has revived an imperial approach in which the ruler personifies the state and the national interest. As he himself put it at a high-level Party meeting in 2016:

“Everything in China is under the direction of the Communist Party: party, state, army, civilian life and education, and at all points of the compass.”

And everything in the Party is now dominated by Xi.

Will it hold? It is generally unwise to take dictatorships at their word. Xi sits at the apex of a series of structural problems at home and is heavily dependent for his legitimacy on the chimera of militant nationalism, combined, of course, with an ambitious system of digital surveillance and coercion.

But this is no longer the Mao era. When Mao Zedong Thought was the national catechism, China was poor, troubled and closed off. Today China is out in the world, a major beneficiary of globalisation, and the Party is now obliged to try to impose its story in the global context. Abroad, as the Global Times, one of the Party’s more extreme mouthpieces put it, China has yet to establish global leadership in ideology and in communications. Expect more demands that business partners, visiting dignitaries and Western scholars kowtow to the Party’s version of history as the price of the relationship.

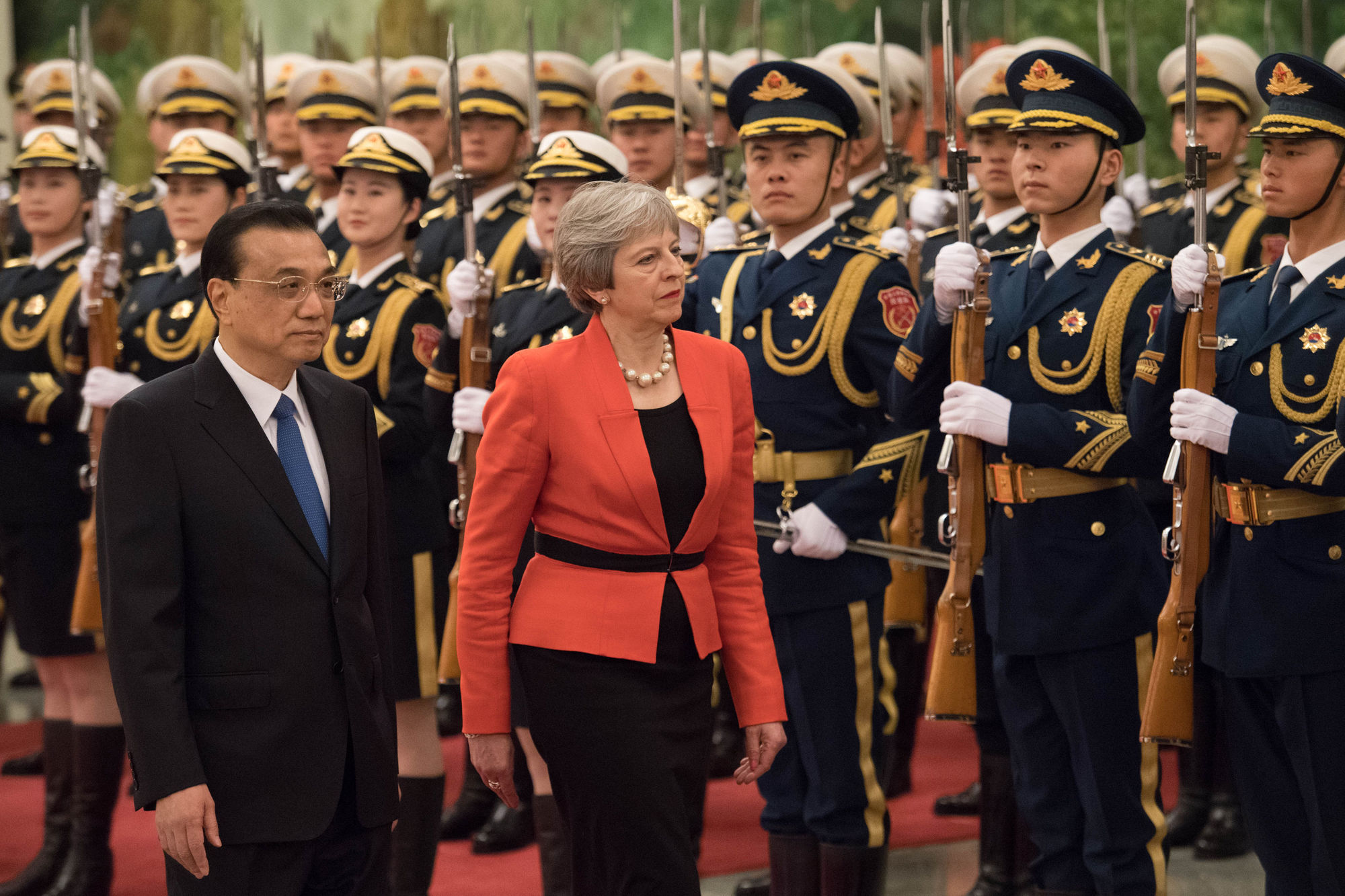

So why was it necessary to remove term limits to the presidency, when Xi’s real power lies in a Party position that has no term limits? Deng Xiaoping, after all, continued to dominate China in later years from his position as Honorary President of the Chinese Bridge Association. One possible reason might be to deprive any rival – perhaps Premier Li Keqiang – of a future power base. If so, then the move is a sign of anxiety rather than confidence.

Succession, however, is the Achilles heel of any dictatorship and, as China’s history teaches us, of the imperial system also: Qin Shi Huang, China’s brutal first emperor, set up a 10,000 year reich that collapsed four years after his death. In the two millennia since, China’s elite power struggles have been savage. Under the People’s Republic, every nominated successor between 1949 and 1989 ended up deposed, in jail or dead. Deng’s settlement gave China an interlude of relative political order. Now that is over, sooner or later, trouble is likely to return.

Read UnHerd’s China (not Trump) series

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe