Billy Graham preaching in Sweden, 1978 (Credit Image: Globe Photos/SIPA USA/PA Images)

The news of Billy Graham’s death has brought back many memories. My first trip to a football stadium, to hear him speak on one of his tours of England in the Eighties; the ways nonconformist churches emulated his ‘altar calls’ as an invitation to receive salvation; the weekly repetition of those words in John 31 in gospel services: “You must be born again.”

Coincidentally, he’s recently been on our television screens, reminding us of his history with Britain in the Netflix drama, The Crown. He made an appearance in the second series as pastoral adviser to Queen Elizabeth II, while she ponders the meaning of forgiveness. Her Majesty is depicted meeting him a couple of times, inviting him for a one-to-one shortly after she has was told of her uncle’s former affiliation with Nazis.

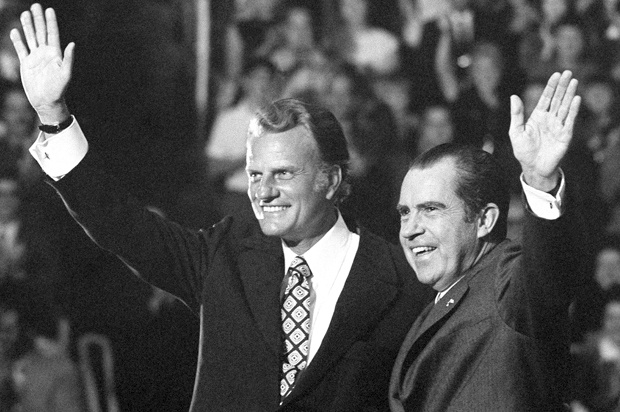

That Graham engaged in such a way, with such a public figure, was unusual. At a time when conservative evangelicals, especially those in ‘low’ churches, were averse to taking a role in public life, Graham not only met the British Queen, but also had a ‘bittersweet’ relationship with Nixon – and one which he later came to regret. His links to Nixon were messy and complicated – and very public. It deterred many people of faith from engaging in politics.

It was a while before white US evangelicals would leave their separatist lifestyles to engage again with public policy, and even then it was only through organisations such as Moral Majority2 which concentrated on a small number of polarising issues.

Graham’s son Franklin has, however, been very vocal in his support for elements of the Trump presidency. While this will have gone down well with many of his humanitarian organisation’s supporters3, it hasn’t made him popular among more progressive Christians. He has been publicly criticised for his political positions by Jerushah Armfield, his niece and Graham’s granddaughter, who suggested he stick to his charity work.

Graham, though, would certainly not want to be remembered for his political engagement. Quite the opposite. He was widely praised for his humility and would frequently argue that his mission was to point people’s attention to Jesus, and not to himself. He wished fervently that his revival meetings could have been advertised without using his name: “I despise all this attention on myself…I’m not trying to bring people to myself, nor am I trying to interest people in me.”

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe