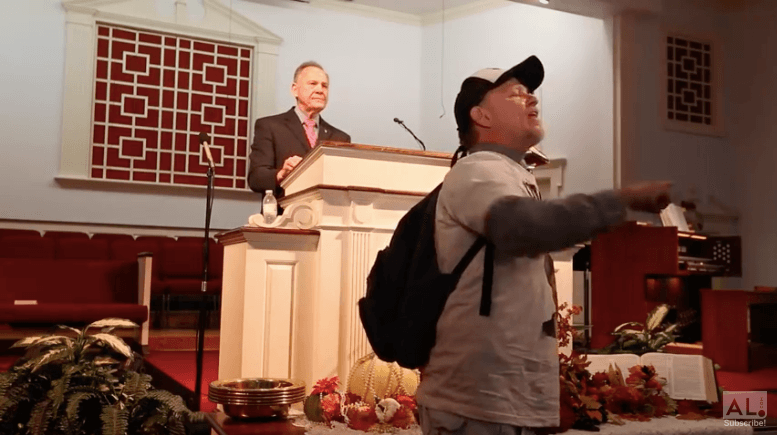

Candidate for U.S. Senate Roy Moore speaks during a candidates' forum in Alabama (Credit Image: CQ-Roll Call/SIPA USA/PA Images)

Last Thursday, late-night comedian Jimmy Kimmel found himself in a Twitter spat with Roy Moore, Alabama’s Republican Senate nominee. The night before, Kimmel had dispatched a comedian from his show to heckle Moore, a former judge and evangelical Christian, during a worship service.

“But the whole town says you did it!” The comedian Tony Barbieri shouted as Moore attempted to address the church on the allegations of sexual misconduct against him. “The entire town? All the girls are lying?” he peppered. Police escorted Barbieri off the property; Roy Moore seized the opportunity.

He took to Twitter to articulate the message that has driven his campaign ever since women accused him of molesting them as teenagers. “If you want to mock our Christian values,” he wrote to Kimmel, “come down here to Alabama and do it man to man.” The meaning was clear: Kimmel’s stunt was motivated by his elite disdain for Alabamians and their love of Jesus. (86% of adults in Alabama identify as Christian.) And if Kimmel could pull such a malicious stunt, who’s to say that the Washington Post hadn’t acted in the same bad faith when they originally rolled out the allegations against Moore?

Kimmel responded on his show: “It doesn’t fit your stereotype, but I happen to be a Christian, too,” he said. “So if you’re open to, when we sit down, I will share with you what I learned at my church. At my church, forcing yourself on underage girls is a no-no.”

Yet Moore had already won, at least in terms of what matters at the polls. The moment crystallized one of the key ways in which Moore has maintained his base of support even as sexual assault allegations have brought down far more powerful men across America. Moore has successfully reframed this race as, quite simply, God versus Everyone Else.

In 2016, Trump captured the imaginations of Americans in both red and blue states not with policy prescriptions or lofty rhetoric, but by distilling his candidacy into the tidy narrative of us versus them. Gone were the days of pretending our politics were anything but tribal. Trump leveraged the power of victimhood, convincing many that the so-called establishment—in Washington, in the media—had been betting against them, and that only he could settle the score. It was basic, primal, and easy to digest. It was brilliant, if it wasn’t also unnerving.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe