While today we know much about the Nazi concentration camps, there is little awareness in the West of the vast extent of its Soviet equivalent – the gulag, the prison camp system first established by Lenin and then enlarged by Stalin.

Although millions were incarcerated in Soviet labour camps, often in the most terrible conditions, there were no newsreel cameras to record their liberation (photographers would have been shot and there was no liberation to record). Released prisoners were too frightened to speak out; former inmates were shunned, denied employment and education, and banned from living in any major cities. By contrast with Willy Brandt’s ‘kniefall’ before the Warsaw ghetto monument, there has been no act of national repentance for excesses of the Soviet Communist era. Today, gulag survivors and their families see Russia governed by a former member of the state body which, in an earlier incarnation, also comprised their guards and executioners.

Soviet Communism’s repression of its citizens represents one of the great crimes against humanity of the 20th Century but the lack of public awareness of it in the West is not only due to the repressors’ success in hiding their tracks. Western enthusiasts for Lenin’s ‘great experiment’ alternately looked the other away, denied the evidence, or actively supported the Moscow regime.

I first became aware of this while I was writing about the Siberian gulag. I came across impassioned speeches in the House of Lords in the early 1930s on behalf of over a million smallholding peasants, the ‘kulaks’, who had been deported in convoys of cattle cars to the far reaches of the Soviet Union. Given only few hours to quit homes they had been born and raised in, many hundreds of thousands of men, women and children were despatched to cut timber for the Soviet export trade. The largest customer for this slave-cut timber was Britain. At today’s prices, it was a trade was worth over £500m a year. Russian logs were the ‘blood diamonds’ of their day.

Intrigued and horrified, I dug deeper. What I found was disturbing. The Labour Party was in government then but had not only denied the eye witness accounts that filtered out from escaped prisoners; ministers had obstructed all attempts to halt the trade and the Cabinet had even blocked an enquiry into conditions in the camps.

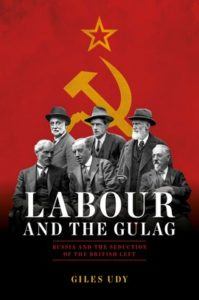

A number of questions followed: Did Labour really know of what was going on? And if they did how could a party which was founded to speak up on behalf of the poor and marginalised ignore such appeals? If they had been deceived about Soviet Communism, how far back did that deception go? How widespread was it? Why were they duped? My original work was laid aside and I began work on what eventually became my book, Labour and the Gulag: Russia and the Seduction of the British Left, published earlier this year.

A number of questions followed: Did Labour really know of what was going on? And if they did how could a party which was founded to speak up on behalf of the poor and marginalised ignore such appeals? If they had been deceived about Soviet Communism, how far back did that deception go? How widespread was it? Why were they duped? My original work was laid aside and I began work on what eventually became my book, Labour and the Gulag: Russia and the Seduction of the British Left, published earlier this year.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe