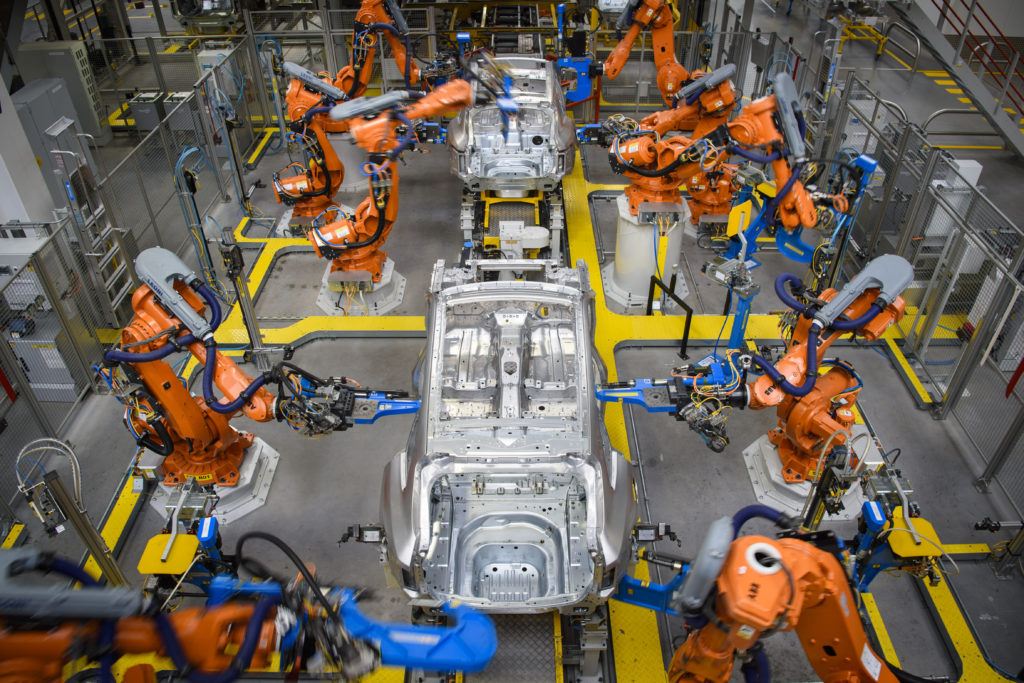

Digihelion, Getty Images

As robots threaten jobs it’s increasingly common, on the right as well as the left, to suggest that we need a “Basic Income” safety-net for everyone[1. Some useful background here from an advocacy group, called the Basic Income Earth Group.]. A kind of pension that you draw all your life. So whether you have a full-time job or not, you won’t starve.

I think there’s a much better answer… but we’ll get to that.

It really isn’t clear if the advance of robotics and Artificial Intelligence will actually destroy more jobs than it creates. If that happens, it will undercut the goal of ‘full employment’ that has been central to the developed economies for more than a century. Full employment doesn’t mean everyone has a job, but it means most people who want one can get one. There’s nothing more important to governments – other than defending the nation from external aggressors – than keeping unemployment down.

While we really don’t know if clever machines will imperil the full employment idea, there are smart voices out there suggesting that, this time, it may really be in danger[2. For example, this PBS programme.].

The latest tech revolution really could lead to a crisis in labour markets. While machines and other tools can’t do everything we can they have always been able to do one or two things much better than we do. Think about the calculator. The chisel. Or the wheel.

The 21st-century contrast with previous ‘industrial revolutions’ lies chiefly in the pace of change. It was John Maynard Keynes, doyen of 20th-century economists, who summed it up like this. If we can economise in our use of labour faster than we can find new jobs, it’s over – the jobs market goes into a tailspin. Capital progressively takes its place as a factor of production. And, whether we like it or not, we all get more and more free time[3. Keynes’ seminal 1930 essay, Economic Possibilities for our Children, is available here.].

Basic Income as the cure-all?

The ‘right’ and ‘left’ versions of Basic Income can be summed up like this. The right would take pretty much all the money we spend on social benefits and divvy it between everyone; so the cost to the economy would be minimal. The left would give everyone something like an old age pension (what Americans call social security) from the age of 18 or 21 – and keep up many of the social benefit payments we make now, except (presumably) unemployment; so the cost would be a lot. Both, however, add up to a ‘lifelong pension’ idea. In several countries there have been experiments running – partly to see how these pension-type payments affect people’s interest in getting actual jobs. Too local, too small-scale and poorly-designed – they haven’t yet told us much, however[4. “Why Finland’s Basic Income Experiment isn’t Working,” by Antti Jauhiainen and Joona-Hermanni Makinen, New York Times, 20 July, 2017.].

Regardless of incentive effects, there’s nonetheless a core problem with Basic Income. That’s aside from the fact that it either strips money away from all sorts of particularly deserving groups (like the disabled and children and people needing housing help) to spread it out equally or, to avoid that downside, it costs a fortune since it becomes an additional benefit and for everyone. The core problem lies precisely in its indiscriminate application to young and old alike.

Let’s imagine an economy in which jobs are eroding, and ‘unemployment’ (if that’s still the term we use) isn’t the 5-10% we’re used to in the more successful developed economies like the UK and the US, but 35%. If everyone has a Basic Income ‘pension’ of $1,000 a month (let’s assume the ‘left’ version), the cost to the economy is $12,000 a year times the adult population – and 65% of these payments are going to people who don’t actually need them. More important, they go to young and old alike. The 22-year-old and the 64-year-old both get the payment, and are equally able to live outside the workforce.

A far better idea lies in Retirement Age Management. Somewhat bizarrely, every developed economy has for more than 20 years been striving – often at some political cost – to raise the retirement age. In particular, the state pension age, which sets the pace. There have of course been good reasons for these changes – a recognition that people now live much longer than they did when state retirement programmes were initiated; a concern for the cost of these efforts; and a desire for equity between men and women. (Uniquely, women have historically benefited disproportionately from retirement payments in many countries. In the UK, for example, females enjoyed a right to retire five years before men (now being phased out)).

Yet these worthy considerations have been rapidly overtaken by events. They assumed steady-state full employment stretching into the indefinite future. If that assumption is flawed, following through on these delayed retirements will prove a costly mistake. Because, of course, extending the retirement age has the effect of increasing the labour force. It requires that there be more jobs, or it will simply add to the total number that is unemployed[5. In the U.S. the ‘full’ retirement age is in process of shifting from 66 to 67. In the UK, it will be 67 by 2027; women, who used to retire at 60, are now ‘catching up’ with men].

The flexible tool

By contrast, Retirement Age Management offers a flexible tool by which governments can use the state pension age to adjust the size of the labour force – and, in the process, the unemployment statistics. Since, broadly speaking, the cost to the economy of state retirement pensions is broadly comparable with the cost of unemployment benefits, there are big advantages in focusing these benefits on citizens toward the end of their working lives – and freeing up jobs for younger people. Even in an economy with significantly fewer jobs, it means that young people can plan to get them and pursue careers. It means that older workers can see earlier retirement as an extra plus. And it avoids the waste in paying Universal Income to people who have no need of it.

These are dramatic benefits. If we do face a drop in the availability of jobs, Retirement Age Management could rapidly be used to adjust the labour market to maintain ‘full employment’, maintain the career opportunities of younger people, and offer earlier retirement as a benefit to older workers (rather than the disaster of unemployment).

So in our current situation, governments might be wise to freeze planned increases in the retirement/pension age. Perhaps they should begin to cut it. In the UK, for example, there could be a big electoral advantage to the party that decided to roll back the increase in women’s retirement age to 60 again – and declare a policy objective of bringing men’s down to 60 too. In the US, the push up to 67 should be abandoned, and consideration given, by stages, to bringing down the “full” social security age to 62 (when currently pensions are available under some circumstances).

The costs involved are less problematic in economies where unemployment benefit is standard and long-term (not the case in the United States). But if we lose the ‘full employment’ norm it will become urgent for every economy to take responsibility for the expanded number of the idle – what Keynes in that famous essay called “the new leisured class”. We don’t know if it will happen, but let’s get prepared.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe