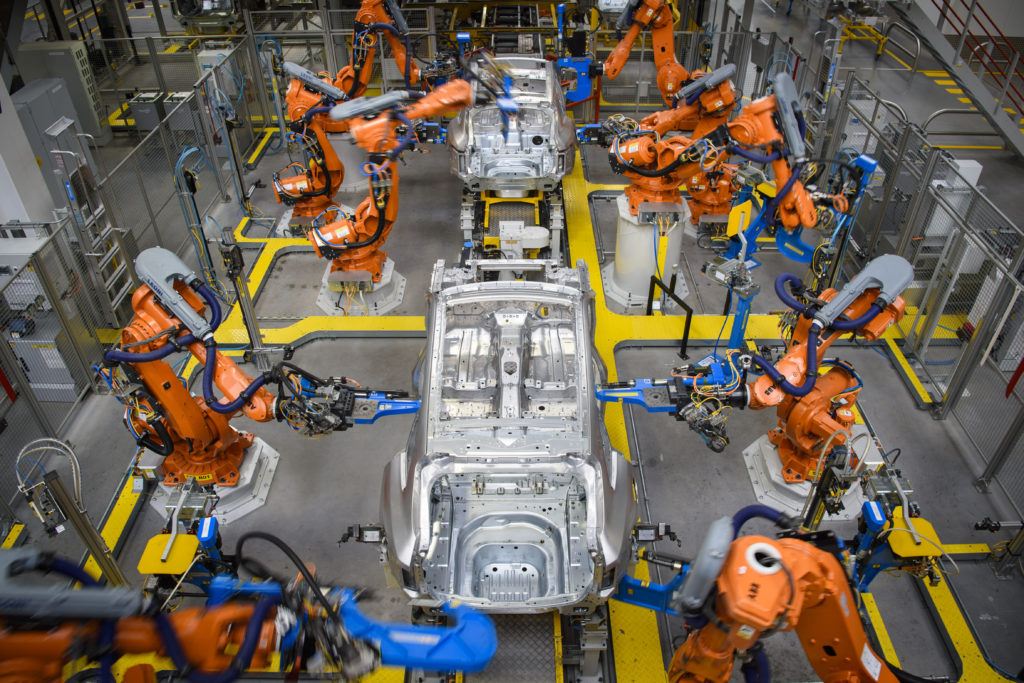

Digihelion, Getty Images

As robots threaten jobs it’s increasingly common, on the right as well as the left, to suggest that we need a “Basic Income” safety-net for everyone1. A kind of pension that you draw all your life. So whether you have a full-time job or not, you won’t starve.

I think there’s a much better answer… but we’ll get to that.

It really isn’t clear if the advance of robotics and Artificial Intelligence will actually destroy more jobs than it creates. If that happens, it will undercut the goal of ‘full employment’ that has been central to the developed economies for more than a century. Full employment doesn’t mean everyone has a job, but it means most people who want one can get one. There’s nothing more important to governments – other than defending the nation from external aggressors – than keeping unemployment down.

While we really don’t know if clever machines will imperil the full employment idea, there are smart voices out there suggesting that, this time, it may really be in danger2.

The latest tech revolution really could lead to a crisis in labour markets. While machines and other tools can’t do everything we can they have always been able to do one or two things much better than we do. Think about the calculator. The chisel. Or the wheel.

The 21st-century contrast with previous ‘industrial revolutions’ lies chiefly in the pace of change. It was John Maynard Keynes, doyen of 20th-century economists, who summed it up like this. If we can economise in our use of labour faster than we can find new jobs, it’s over – the jobs market goes into a tailspin. Capital progressively takes its place as a factor of production. And, whether we like it or not, we all get more and more free time3.

Basic Income as the cure-all?

The ‘right’ and ‘left’ versions of Basic Income can be summed up like this. The right would take pretty much all the money we spend on social benefits and divvy it between everyone; so the cost to the economy would be minimal. The left would give everyone something like an old age pension (what Americans call social security) from the age of 18 or 21 – and keep up many of the social benefit payments we make now, except (presumably) unemployment; so the cost would be a lot. Both, however, add up to a ‘lifelong pension’ idea. In several countries there have been experiments running – partly to see how these pension-type payments affect people’s interest in getting actual jobs. Too local, too small-scale and poorly-designed – they haven’t yet told us much, however4.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe