That’s no longer true, Piketty argued, because Western societies are reverting to historic type, with low social mobility and resources and opportunities dominated by a well-connected elite who too often came into money by birth. An inherent feature of capitalism, ever-rising inequality can only be tempered, said Piketty, by heavy state intervention – including an income tax rate of up to 80% and an annual 2% tax on wealth. Unless that happens, he concluded, the result will be chronic social and economic instability, leading to a toppling of the democratic order.

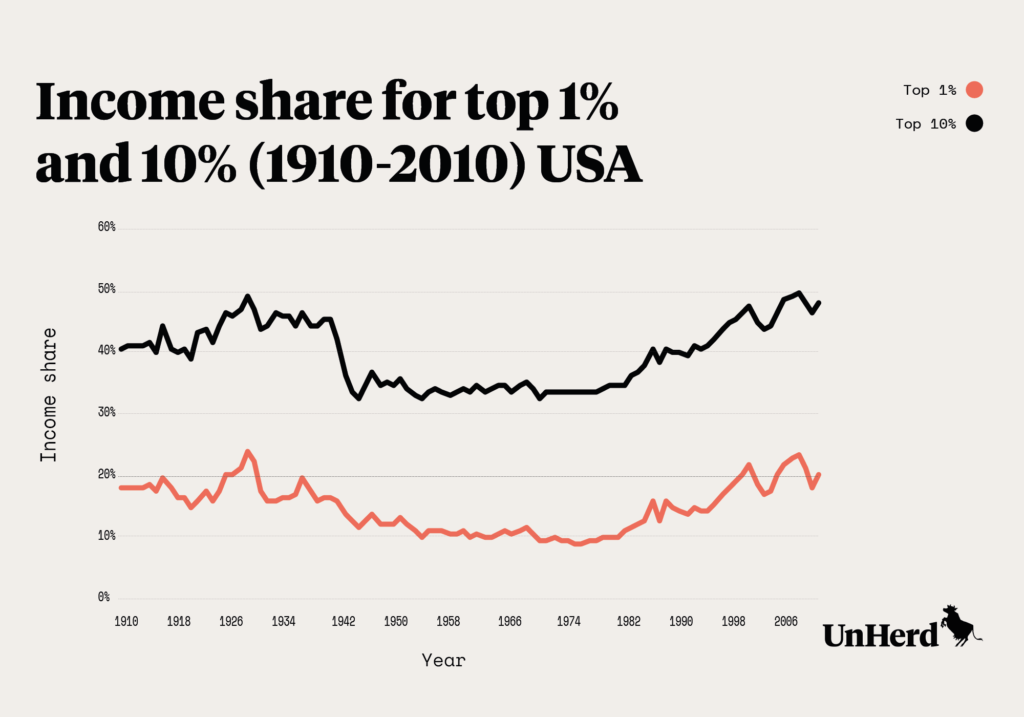

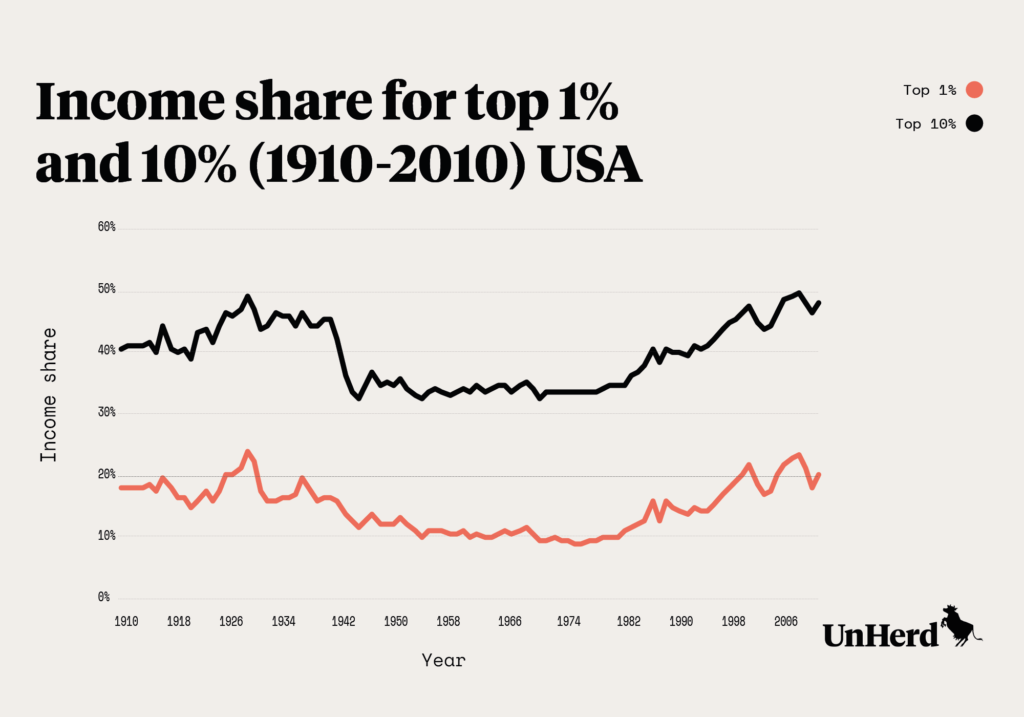

Piketty’s warnings should not be dismissed – not least as the descriptive analysis in Capital rests on firm empirical foundations. While there is a debate to be had about the extent to which income inequality is rising across the Western world, the distribution of wealth has undoubtedly become far more unequal.

Yet, when it comes to capitalism, Piketty is far too pessimistic. The 2008 Lehman collapse and its aftermath, for instance, far from highlighting the drawbacks of capitalism, as Piketty and his many admirers maintain, shows what happens when you mess with capitalism so much it mutates into something “cronyist” and destructive.

The financial crisis happened because ‘independent’ central banks, egged on by myopic politicians, pumped up equity and debt markets with cheap money. Bank regulations, designed to keep markets relatively orderly, had meanwhile been severely diluted courtesy of Wall Street’s campaign cash. The ‘financial elite’ was then shielded from the wreckage it had caused, as banks’ vast losses were shoved onto taxpayers.

None of this utterly outrageous behaviour is due to ‘free markets’ as, at every turn in this sorry saga, free markets have been traduced. Rather than too much capitalism, the financial crisis happened because there wasn’t enough.

I also don’t accept Piketty’s assertion that, under capitalism, inequality will inevitably rise. “Widening and deepening inequality isn’t driven by immutable economic laws,” the Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz once told me. “A well-functioning market economy doesn’t only create jobs, but should also generate increases in income that are shared”.

The key part of that argument, of course, is “well-functioning”. And Western capitalism in the twenty-first century is functioning rather less well than it should. Too-big-to-fail banks that extort government bailouts are anathema to free markets. Monopoly corporations using their power to restrict competition and exploit consumers are anathema to free markets.

Being pro-market does not always mean being pro-big business. It often means precisely the opposite

-

An oligopolistic house-building sector, deliberately restricting the supply of new homes to keep prices and profits high, is anathema to free markets. Plummeting social mobility is anathema to free markets – undermining the social contract upon which capitalism is built. These trends are increasingly apparent in modern Britain. That’s why the UK’s broad cultural and political acceptance of free markets is now being questioned. That’s why urban trendy types are increasingly quoting Marx.

Capitalism need not lead to ever-rising inequality, provided the right checks and balances are in place. We must face down behaviour that causes systemic instability, or involves excessive corporate greed – implementing regulations that work. Being pro-market does not always mean being pro-big business. It often means precisely the opposite.

This weekly column is called Tarbell – named after an American journalist of the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century. A writer who believed strongly in capitalism and enterprise, Ida Tarbell also understood the vital importance of reining in capitalism’s excesses. From humble origins, Ida rose to the pinnacle of American journalism, tackling the economic and business issues of her day with skill, determination and courage. It was Tarbell who exposed the criminality of Standard Oil, forcing Teddy Roosevelt to become the ‘trust-busting’ President. But it was also Tarbell who defended mechanisation and technological progress – arguing, correctly, that rising productivity and living standards, ultimately help create a better, more prosperous society for all. And, yesterday, UnHerd published my film about her life and example.

This column will, in the weeks and months to come, look at economic, business and political issues from the same perspective as Tarbell. The author supports capitalism, but is mindful that it must be tempered lest it lose public consent.

As for Marx, the irony is that he never said the quote at the start of this article. It was “the rule of the bourgeois democrats”, he told the Central Committee to the London Communist League in March 1850, not capitalism, that “will carry the seeds of its own destruction”. Under Marxist theory, ‘bourgeois democracy’ is essentially a government that serves only in the interests of the wealthy and well-connected. That’s one warning from Marx I am fully prepared to accept.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe