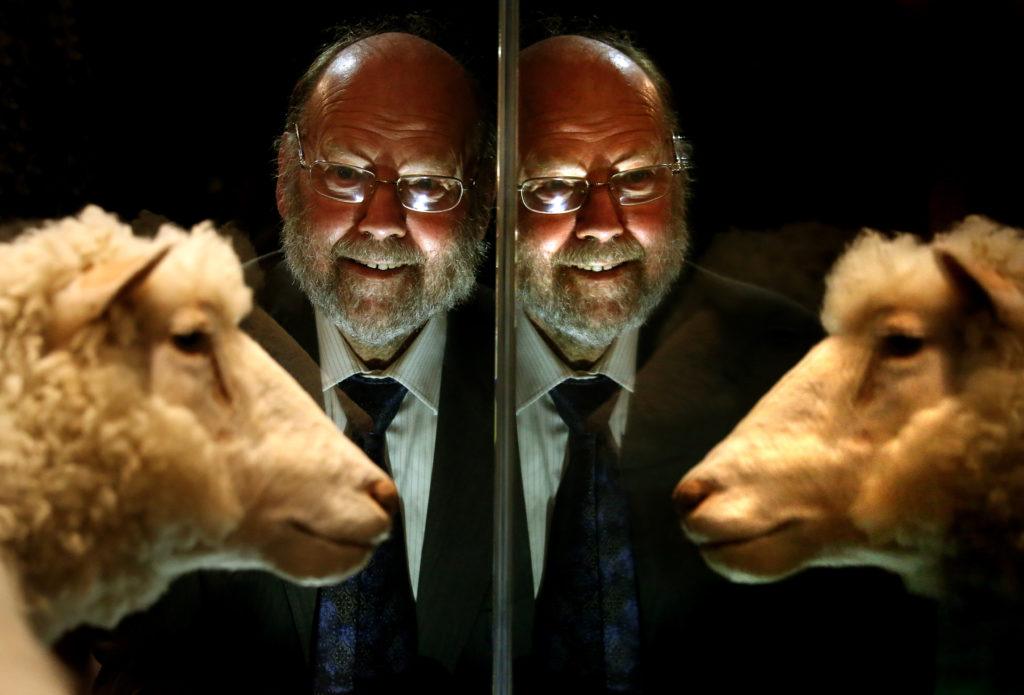

When Dolly the Sheep was cloned, the news spread around the world like a tsunami.

Within days, President Clinton demanded a report from his ethics gurus. Soon afterwards, the uncomprehending celebrity sheep was staring out from the covers of Time and Newsweek. There were hearings in the US Congress, and dozens of other national legislatures – and then years of anguished debate at the United Nations.

Yet, at the end of the day, cloning is just biological photo-copying. The Dolly technique hasn’t led to cloned human babies. Some wealthy eccentrics have used it to replicate beloved pooches. The only serious application seems to be in cattle breeding.

Meanwhile, fast forward 20 years, and the focus is on genetics, where there have been two huge developments.

Genetics for all

First, genetics has gone retail. The term of art is ‘consumer genomics’. As the cost of analyzing our genes has plummeted, enterprising companies – led by 23andMe – are offering to sell us our genetic secrets. And consumers – from ancestry researchers to health worriers to the plain curious – have been responding in droves. A half-price self-testing kit was recently a top seller in a sale on Amazon.1

Second, with little fanfare outside the technical press (the contrast with the cloning brouhaha is astonishing), we’ve come up with a dramatic new technique that actually enables us not just to analyse our genes, but to re-engineer them. It’s been given a curious name, which has no doubt helped keep it obscure. CRISPR-Cas9.2

The pros are fascinated. But they have also expressed alarm. At a meeting urgently convened by the US National Academies, America’s top scientists invited their Chinese and British counterparts to help hash out its implications – and they called for a moratorium on most uses of it with humans.3

The technique is dramatic. According to Harvard’s George Church, this is how it re-engineers the genes:

“It’s the fastest thing I’ve seen yet. It’s like you throw a piston into a car and it finds its way to the right place and swaps out with one of the other pistons – while the motor’s running.”

And we’ve already begun to apply these techniques in many contexts – from ants and mosquitoes to human embryos.4

There was something simple and visual and haunting about Dolly being cloned. CRISPR-Cas9 is complex and abstract and presented in the context of all manner of advantageous possible applications. How is it being reported?

Clickbait time?

Typical of the enthusiasm with which much of the press has greeted these developments, NBC’s website turns them into a listicle of 11 items under the headline: “11 Amazing Feats the Gene-Editing Tool CRISPR Just Made Possible”5. And some of these claims are certainly amazing. Part of the problem with this kind of science reporting, of course, is that the most dramatic and positive and hopeful spin is put on every single item; it’s more marketing hype than reportage. Cancer, superbugs and mosquitos are all listed along with inheritable diseases – for example, experimental work in mice with Huntington’s Chorea. Of this last possibility, the article breathlessly concludes:

“Experts expect this promising technique to be applied to humans in the near future.”

The implication of this sentence is that families with Huntington’s just need to wait around and await the definitive cure.

On the one hand, on the other hand?

More soberly, here is the New York Times6: “while a long way from clinical use, [CRISPR-Cas9] raises the prospect that gene editing may one day protect babies from a variety of hereditary conditions.” Note the cautions: “long way… raises the prospect… may one day.” Not the stuff of clickbait listicles; reporting rather than hype.

The New York Times’ observation lies in a review of the issue and its challenges sparked by the latest research report – of fixing a heart-defect gene that could cause death in later life. Pulitzer Prize-winner Pam Belluck, while concluding with reassuring words from lawyer and bioethicist Alta Charo who “doubts that a flood of couples will have ‘edited children,’” is prepared to start out by asking some hard questions:

“… the achievement is also an example of human genetic engineering, once feared and unthinkable, and is sure to renew ethical concerns that some might try to design babies with certain traits, like greater intelligence or athleticism.

“Scientists have long feared the unforeseen medical consequences of making inherited changes to human DNA. The cultural implications may be just as disturbing: Some experts have warned that unregulated genetic engineering may lead to a new form of eugenics, in which people with means pay to have children with enhanced traits even as those with disabilities are devalued.”

Charo’s response to such concerns is neatly summarized: “Sex is cheaper and it’s more fun than IVF, so unless you’ve got a real need, you’re not going to use it.” On the other hand, one might ask whether a “flood of couples” will be needed if a handful of wealthy couples decide they want to use technology to give eugenic advantages to their children.

In Britain’s Daily Telegraph7, Henry Bodkin also reports on the latest CRISPR research while noting the ethical context. Somewhat pointedly, he observes that:

“In the last two years, scientific opinion in the US has grown more sympathetic to germline editing, where a genetically modified child can pass on changes to future generations. In 2015, bioethicists at the National Academy of Scientists (NAS) said it would be ‘irresponsible’ to use gene editing technology in human embryos for therapeutic purposes until safety issues were resolved. But earlier this year, NAS and the National Academy of Medicine said scientific advances had made the procedure a ‘realistic possibility that deserves serious consideration’.”

He concludes by quoting Dr. Helen O’Neill of University College, London, who laments that:

“Unfortunately, the news about the potential ability to correct disease has been eclipsed by the fear of so-called ‘designer babies’. The technology to support research into correcting diseases is readily available and is largely limited only by legislative barriers.”

In other words, legal constraints and public fear of ‘designer babies’ are getting in the way of research and clinical applications.

Or is the sky falling?

Writing in The Guardian, biologist and technology critic David King lays out his concern lest “consumer genomics” lead to “consumer eugenics.” Noting that consumer approaches to surgical “enhancement” generally reflect the use of money to adapt our bodies so they conform to conventional notions of perfection, he fears exactly the same tendency with interventions at the gene level:8

“Once you start creating a society in which rich people’s children get biological advantages over other children, basic notions of human equality go out the window. Instead, what you get is social inequality written into DNA. Even using low-tech methods, such as those still used in many Asian countries to select out girls (with the result that the world is short of more than 100 million women), the social consequences of allowing prejudices and competitiveness to control which people get born are horrific.

“Most ‘enhancements’ in current use, such as those in cosmetic surgery, are intended to help people conform to expectations created by sexism, racism and ageism. More subtly, but equally profoundly, once we start designing our children to perform the way we want them to, we are erasing the fundamental ethical difference between consumer commodities and human beings. Again, this is not speculation: there is already an international surrogacy market in which babies are bought and sold. The job of parents is to love children unconditionally, however clever/athletic/superficially beautiful they are; not to write our whims and prejudices into their genes.”

On reporting CRISPR-Cas9

There’s no one standard way to report on technological achievements, including controversial ones, though there are better ways and worse ways. Comment/OpEd pages properly give opportunity to those with clear and often strongly-held views. Clickbait listicles can be fun – and also useful to those few readers who go beyond them to review the original articles they collect.

But what about news reporting? This has hardly been a scientific survey of CRISPR-Cas9 reportage; it’s a sampling, but it’s one that will withstand scrutiny, at least in the English language press.

While the New York Times piece is a more serious piece of writing, the NYT and the Daily Telegraph are both examples of a distinctive genre. There’s a pattern. Perhaps they teach this in journalism school.

To report a tech or scientific achievement, the lede needs to focus on the achievement or promise. Then a few paras later note that it “raises questions” about ethics (or safety, or some other external factor). Then carry on with the descriptive material on the research, its potential benefits, the scientists involved, and so on. Then return to the ethics issue, and conclude with a quote, from someone in a position of authority, to reassure the reader that all is well. All those anxieties we raised six column inches earlier can be laid to rest. Serious, smart, expert people aren’t bothered about them. Sex is fun and inexpensive, so why would everyone decide to use in vitro fertilization to get a designer baby (as the NYT quotes bioethicist Alta Charo)? Or, in the Telegraph’s version, all we need is to get moving with curing diseases is getting rid of restrictive laws supported by people with an irrational fear of “designer babies” (as the doctor from UCL tells us).

It’s an effective formula, at least from one perspective. It checks the ethics box, though it then uses the discussion of ethics to dismiss the ethical concerns that have been raised. One problem with this approach is that – as Dr. Helen O’Neill implies – policy choices are fundamentally related to popular opinion. Whether or not we take the view that ethical issues are significant in themselves, they are hugely important in shaping citizens’ perceptions of technology and therefore the frame of reference for policymaking.

Yet the net effect of reporting and then dismissing ethical issues, deliberately or otherwise, is to assist in ‘laundering’ the technology of its ethical questions, and thereby promoting it. At a minimum, a respectful citing of ‘experts’ taking different views would establish that these issues are open and needing to be addressed.

The contrast with the cloning controversy is instructive. Right from the start, most reporting focused on the ‘brave new world’ spectre raised by Dolly’s cloning. Editors plainly decided that cloning – at least, potential cloning of humans – was beyond the pale, and that reporting could focus on the controversy, not the technology itself. A more extended review would examine how the cloning issue soon merged with controversy about human embryonic stem cell research; and also, how the Raelian cult – led by a French-Canadian former racing-car driver, and committed to cloning – succeeded in dominating the news with its outlandish claims of clonal human births.

But this simple point seems clear. We need a model for reporting controversial science and technology developments that can combine with equal seriousness the science and the ethical questions. The model on display in these pieces from the New York Times and the Daily Telegraph was not that one.

A DISCLOSURE

I know David King, Alta Charo, George Church and Greg Stock (see further reading) personally (though not well); none was consulted in the writing of this piece. Also, I served as an advisor to the US delegation to the United Nations General Assembly in the UN cloning process referenced.

***

FURTHER READING

There’s a huge literature on the issue of human “enhancement,” whether biologists and technologists should be free to develop such techniques, and whether people should be free to avail themselves of them. For example:

- Peter Franklin: Are you on CRISPR? You soon will be.

- Engineering the Human Germline: An Exploration of the Science and Ethics of Altering the Genes We Pass to Our Children (2000, Oxford University Press) (Co-editor with John Campbell).

- Redesigning Humans: Our Inevitable Genetic Future (2002, Houghton Mifflin)

- Also of continuing importance is the short essay by C.S. Lewis, dating from 1943, on the question of making inheritable genetic changes: “The Abolition of Man.” Available here.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe