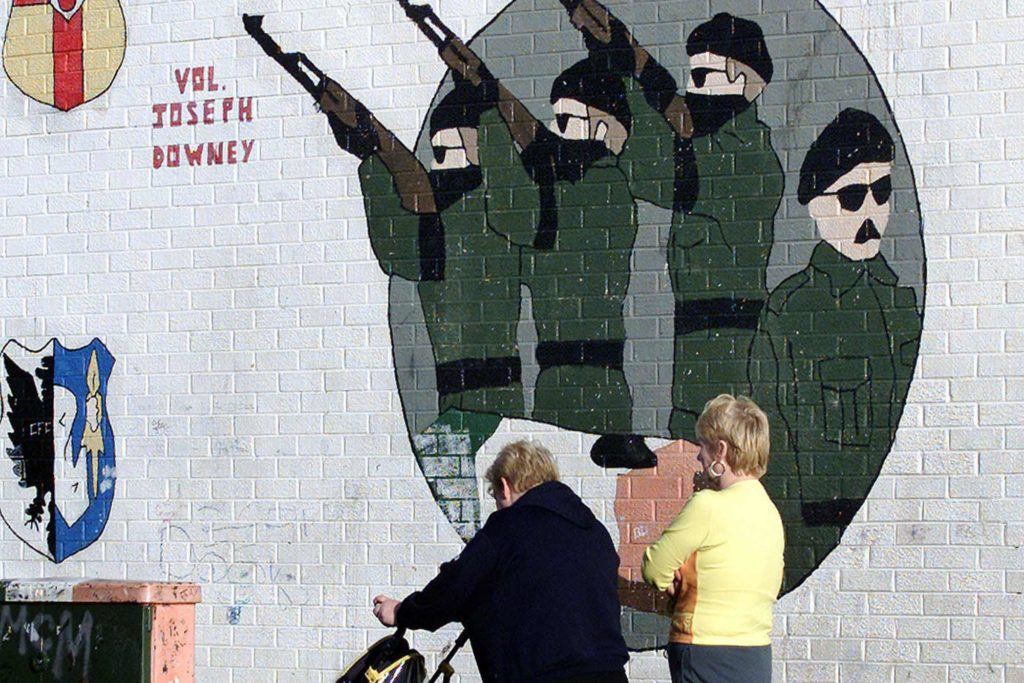

Sean O'Callaghan, 1981 - PA Images/PA Archive/PA Images

The death of Sean O’Callaghan, the former IRA man who became one of the most formidably effective opponents of that organisation, has been greeted by some diehard Irish republicans with cheap glee, crude slurs and a plethora of guffawing emojis on social media. None of that would have come as any surprise to him – he was well used to such stuff – but I’m inclined to think he had the last laugh. The IRA has a long and bitter memory, and O’Callaghan had been its target ever since news of his work for the Irish police from inside the IRA broke in the 1990s. Yet he eluded republican vengeance earlier this week to end his days in a swimming pool in Jamaica while visiting his daughter, surrounded not by hatred but by love.

I first met O’Callaghan in person in London while I was working as a newspaper reporter, shortly after he was released from Maghaberry prison in 1996. We became friends and remained so. I was aware of his complicated history. I had grown up in a Protestant, Unionist family near Belfast and had no time for the romantic delusions of either the IRA or the loyalist paramilitaries, which had resulted in so much sectarian killing and misery. Nor did Sean, who had been raised in a staunchly Republican family in Tralee, County Kerry. In conversation he was eloquent, droll and sharp in his analysis, and there were aspects to his thinking and behaviour which were immediately and strikingly different from those on display among the IRA leadership.

Unlike Gerry Adams, who even now bizarrely denies ever being a member of the IRA, O’Callaghan publicly admitted that he had joined the organisation as a teenager. He was openly remorseful about the killings in which he was involved as a 19-year-old IRA man when the Troubles were at their feverish height. In 1974 he had taken part in an IRA mortar attack that killed a 28-year-old UDR Greenfinch called Eva Martin, and later murdered a Catholic RUC Detective Inspector called Peter Flanagan in an Omagh bar.

These were ugly, wrong and cruel acts, and O’Callaghan took moral responsibility for them. He never afterwards sought to dismiss his victims as “legitimate targets” or otherwise to excuse his actions by hazy euphemism or historical circumstance, as did so many other former paramilitaries. Instead, he faced up to the bleak depth of what he had destroyed, writing that Eva Martin was “not the faceless military target I had imagined” but “an intelligent, attractive woman, head of the modern languages department at Fivemiletown High School.” On Peter Flanagan he said: “I probably ended up murdering the very best type of policeman that Northern Ireland could really have done with.”

Shortly after Flanagan’s murder, he later said, the thought had flashed into his head: “You’re going to have to pay for this some day.” Such flickers of culpability may not be uncommon among perpetrators, but what was unusual was that the person who ensured that O’Callaghan paid for it was O’Callaghan himself. Between 1979 and 1988 he voluntarily returned from London to Tralee to rejoin the IRA and work as an unpaid intelligence agent for the Irish police, saving many lives.

The value of his information was acknowledged by the former Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald, who wrote in The Irish Times of “the debt we all owe to Sean O’Callaghan’s courage and commitment”. One of his biggest successes was a tip-off resulting in the 1984 interception of a seven-ton arms haul from the US on the Irish shipping vessel the Marita Ann, which resulted in the prominent IRA man Martin Ferris receiving a ten-year jail sentence. In 1988, fearing that his cover was about to be blown, O’Callaghan turned himself in to the British authorities for the 1974 murders and received a life sentence which was lifted by royal prerogative in 1996.

He had abandoned any romantic vision of the IRA by 1975, when a senior IRA colleague, Kevin McKenna, casually remarked after news broke of the murder of an RUC woman: “I hope she was pregnant and they’ve got two Prods for the price of one.” Thereafter O’Callaghan’s opposition to sectarianism, fanaticism and their fellow-travellers became the dominant theme of his life and writing, whether applied to Ireland itself or later to Islamist extremists.

Main Edition

Main Edition US

US FR

FR

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe