Oldham From Glodwick painting – James Howe Carse, public domain

It’s fast becoming a well-known fact amongst economists, but one which isn’t often aired in public: there is a correlation between the state and prosperity. And it’s not a negative correlation. It’s strikingly positive.

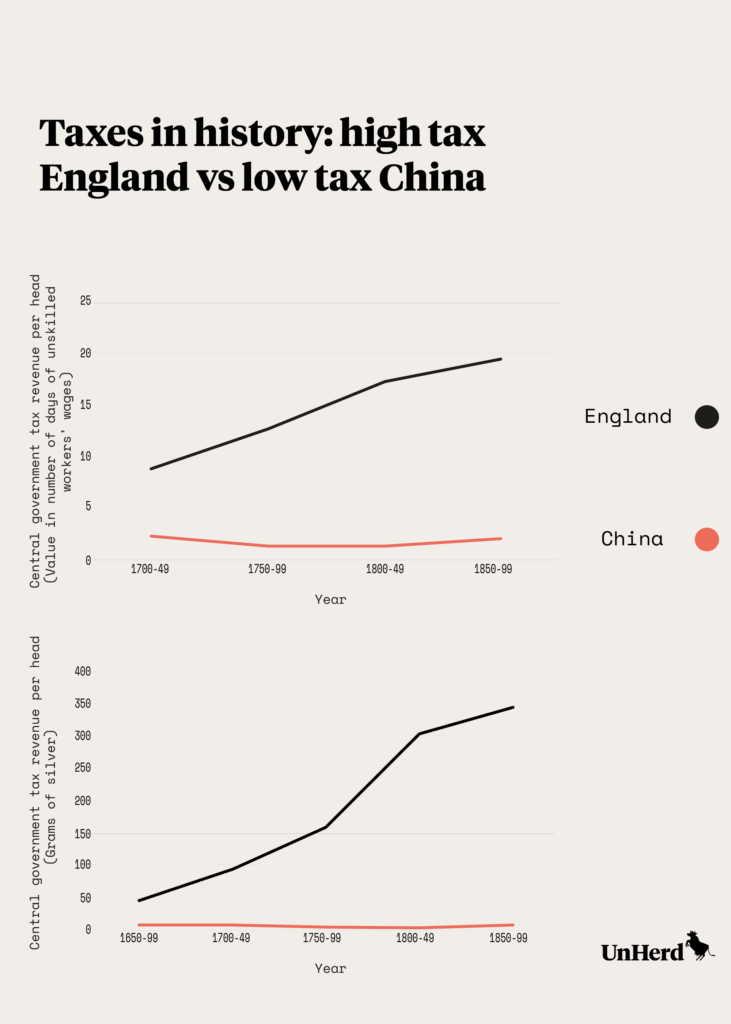

Alongside the astronomical rise in living standards over the last two centuries, we have seen an unprecedented expansion of the state. Whilst the tax take of preindustrial states typically represented less than 5% of GDP, in the typical modern day OECD country taxes represent 20-40% of GDP.[1. Noel Johnson and Mark Koyama, ‘States and economic growth: Capacity and constraints’, explorations in Economic History, 2016] And, perhaps ironically, it wasn’t a low-tax part of the world that spurred the process of modern economic growth. It was high-tax Britain that was home to the first industrial revolution in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Not only do comparisons across the ravages of time suggest that states and prosperity go hand in hand, so do comparisons across countries today. Indeed, some of the poorest parts of the globe lack well established and capable governments. They also tend to be fragmented and experience significant internal conflict, including civil war. As economists Noel Johnson and Mark Koyama note:

“Today’s richest countries possess both sophisticated market economies and powerful, centralized, states. In contrast, the poorest people in the world tend to live in regions with dysfunctional markets and weak or failed states”.[2. Ibid.]

The conclusion of a 2013 report for the National Bureau of Economic Research was as follows:

“[i]t is now widely recognized that the weakness or lack of ‘capacity’ of states in poor countries is a fundamental barrier to their development prospects. Most poor countries have states which are incapable or unwilling to provide basic public goods such as the enforcement of law, order, education and infrastructure”.[3. Daron Acemoglu, Isaías Chaves, Philip Osafo-Kwaako and James Robinson,‘Indirect Rule and State Weakness in Africa: Sierra Leone in Comparative Perspective’, The National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2014]

Even in the US, where there is a tradition of arguing that the state is inimical to growth, there is increasing evidence of a historic link between the state and prosperity. That includes the work of Alex Marshall, author of The Surprising Design of Market Economies,[4. Alex Marshall, ‘The Surprising Design of Market Economies’, University of Texas Press, January 2012] and that of Daren Acemoglu, Jacob Moscona and James Robinson, who, using postal stations as a proxy for state infrastructure in history, find a strong link with innovative activity, as measured by patents.[5. Daron Acemoglu, Jacob Moscona, and James Robinson, ‘State Capacity and American Technology: Evidence from the Nineteenth Century’, American Economic Review, 2016]

The positive correlation between the state and prosperity is hard to square with the popular idea that having a small government is necessary for building a rich economy. It’s difficult to deny the fact that big government can indeed be bad for the economy. Ask any New Yorker about William M. Tweed,[6. ‘William M. Tweed’, Wikipedia, accessed 24 August 2017] one of the most corrupt politicians the city has ever known, and you’d soon understand why America is much more sceptical of big government than is Europe. And we all know the problems with communism and central planning.

So how do we explain the fact that many of today’s richest economies also have sizeable states?

State capability matters more than size

One possibility is that what matters is not so much the size of government but how capable it is. Economists define state capability as the capacity to collect taxes to fund public goods like defence and infrastructure, and to enforce law and order across its geographical territory. In other words, state capability requires both fiscal and legal capacity. However, state capability only seems to work in the best interests of society where it is combined with two other factors.

The first is markets. Markets are a necessary if not sufficient driver of economic prosperity,[7. Victoria Bateman, ‘Lessons from history: how Europe did (and didn’t) grow rich’, University of Cambridge, 24 March 2013] and so the state needs to use its capacity to work with them rather than against them. Where taxes are used to build transport and digital infrastructure that support market activity, it is more likely to have a beneficial effect. Prosperity and the state will go hand-in-hand. However, when taxes are instead used to build palaces, suppress opponents or wage unnecessary wars, the outcome is likely to be altogether different.

In a recent study of twentieth-century China, Yi Lu, Mona Luan and Tuan-Hwee Sng[8. Yi Lu, Mona Luan and Tuan-Hwee Sng, ‘The Effect of State Capacity Under Different Economic Systems’, available at SSRN, 6 February 2016] found that the number of communist party officials in a region had a negative effect on economic activity before the introduction of market reforms in 1978, but then had a positive correlation with numerous measures of economic performance thereafter, including growth in agricultural output, mortality rates, educational outcomes, and local infrastructure development. In their own words:

“Our findings suggest that state capacity could indeed accelerate development, but the effect is substantial and unambiguous only when the state seeks to complement the market instead of substituting it”.

The second factor is constraints on government. Where there are constraints on government that incentivise it to work in the best interests of the population, it is more likely that we will find a positive as opposed to negative relationship between the state and prosperity. Where that is not the case, it is unlikely that the state will work in the best interests of the population indefinitely, and at some point the result will be that it cannot continue to function, either as a result of revolution from within or being conquered by richer and more successful powers from abroad.

Democracy is key both to a capable state and a flourishing economy

The second way of resolving the paradoxical link between prosperity and the state is that rather than the state and prosperity being causally connected, both higher taxation and higher levels of prosperity could have a common underlying cause.

One such common cause could be democracy. Drawing on the historic Qing Empire, economists Debin Ma and Jared Rubin[9. Debin Ma and Jared Rubin, ‘The Paradox of Power: Understanding Fiscal Capacity in Imperial China’, August 2016] argue that autocratic regimes can in fact find it difficult to build state capacity, including the capacity to tax. In contrast, in states with constitutional constraints, such as in England after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the greater trust between the state, the public and administrative officials enabled fiscal capacity to be built. The development of this capacity enabled higher levels of taxes to be extracted by the central state on a consensual basis, so long as they were used in the best interests of taxpayers.

Since constraints on government also help support economic growth, such as by underpinning property rights, then it is inevitable that we would find a correlation between prosperity and the tax take of central government. The lesson is that the correlation between the two does not simply reflect the fact that higher taxes can sometimes be useful in supporting property creation, but that the background institutions that are creating incentives for economic growth also create the ability for the state to tax when needed. It is a matter of correlation not causation, driven by a factor in common to both taxation and prosperity.

Economic prosperity increases demand for the state

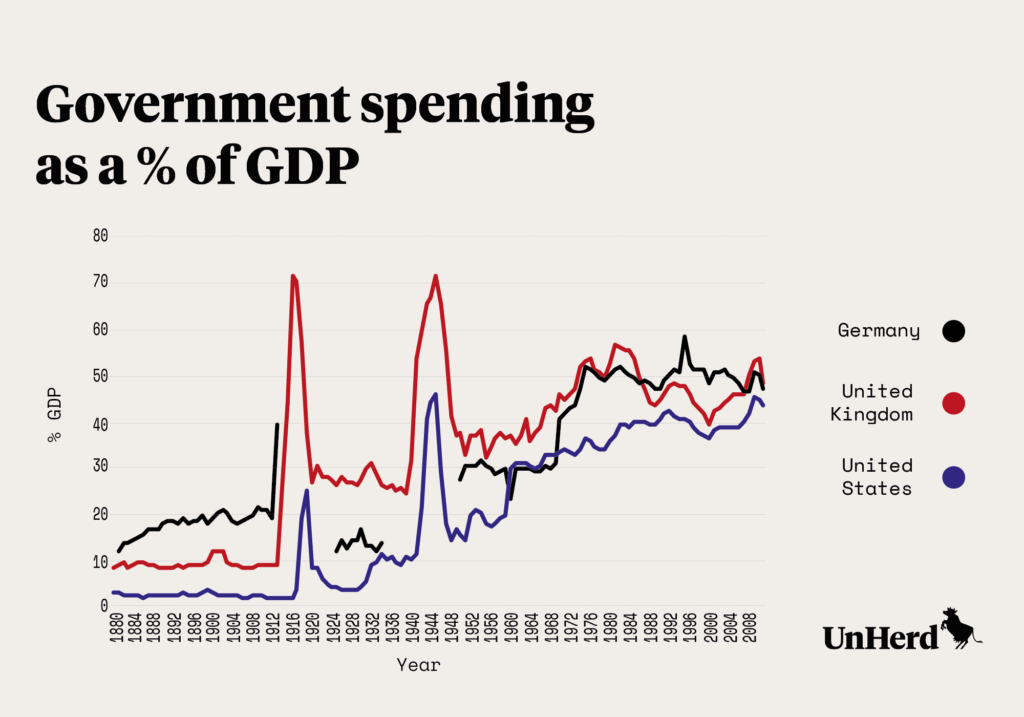

The third and final way of resolving the paradox is to reverse causation: to consider the way in which greater prosperity might in turn fuel demand for government. That’s how the historian Avner Offer explains the significant state expansion of the twentieth century (see chart below).[10. Avner Offer, ‘Why has the Public Sector Grown so Large in Market Societies? The Political Economy of Prudence in the UK, c. 1870-2000’, Oxford Economic and Social History Working Papers, March 2002]

Once we are rich enough to meet our everyday needs, Offer suggests that we start thinking about investing in our long term welfare, such as through healthcare, education and pensions. The only problem is myopia. In his own words, the tax system then provides “a commitment device which helps individuals overcome myopic preferences”.

That still, however, cannot explain the fact that Britain’s state was already sizeable in advance of the nation’s rise to fame. What is, however, worth noting is that England was precocious in developing internal markets centuries before many other European countries. Whilst internationally the nation was something of a backwater, internally it was highly commercial. And with that commercial activity came a nascent welfare state in the form of the Poor Laws.[11. ‘English Poor Laws’, Wikipedia, accessed 24 August 2017] It was a welfare state that picked up the slack as society began to change: as it moved away from traditional family and feudal structures and towards the market. It helped to support the elderly and those incapable of working, thereby freeing younger generations – and women – to more fully engage in the market. Whilst it was by no means a perfect relationship (or a perfect system), the state and the market were already dancing – rather than conflicting – with one another from very early on.

How Britain was able to develop state capacity, together with democratic institutions and a respect for the market, is another question entirely. And it could not be more important given that so many parts of the world have been unable to do so. It’s a question I will therefore turn to next time.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe