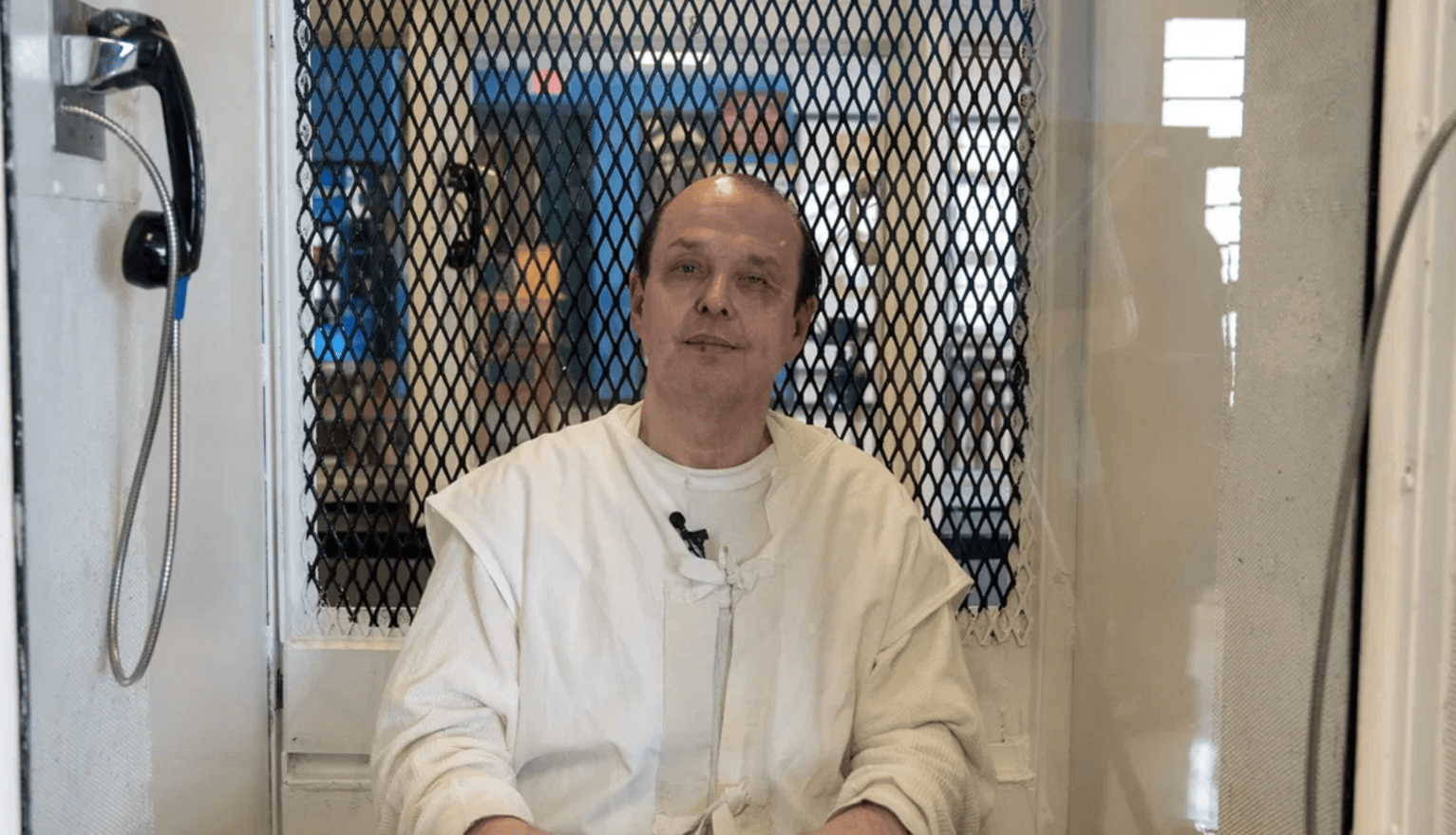

What nearly became the last hours of Robert Roberson’s life can barely be imagined. On Thursday evening, he sat for hours in a cell next to the death chamber at a Texas state prison awaiting execution for an act that may well not have been a crime at all: the death, over 20 years ago, of his infant daughter Nikki.

While three successive Texan courts decided whether to grant a reprieve, Roberson endured what must have felt like torture. Relief came just 90 minutes before his scheduled execution, when the Texas Supreme Court issued a temporary stay. Next week he will get a final chance to present evidence of his innocence.

In one respect, this case is exceptional: Roberson would have been the first prisoner in the US to be executed on the basis of “shaken baby syndrome”, a pseudo-medical concept that describes the shaking to death of infants that should have been consigned to forensic dustbin long ago.

Its other aspects are all too typical, and include serious flaws in the procedural safeguards for those accused of capital offences, a slow and ineffective appellate process, and the psychological trauma inflicted on those sentenced to death. It also illustrates a gap between justice in the US and international law.

The revelation that forensic science is neither immutable nor infallible has for the past few decades undermined confidence in criminal justice systems worldwide. Shaken baby syndrome is an especially fallible category.

Starting in the Seventies, British and American prosecutors secured murder convictions with testimony from “experts” who said that when a baby died without fractures or visible wounds, their death resulted from a “non-accidental head injury” caused by someone taking care of them. They claimed that intracranial injuries such as cerebral bleeds were proof of a violent death, and could only arise from shaking. Any other explanation offered by a parent — such as a fall — was deemed to be a lie.

However, since Roberson’s trial in 2003, there has been an enormous shift, and the consensus now is that intracranial injuries are not infallible evidence of homicide at all. In 2020, the American Association of Paediatrics determined that shaken baby syndrome had been misinterpreted by legal and health authorities.

On both sides of the Atlantic, this has led to successful appeals, and if Roberson gets a new trial, the jury will be told that the prosecution’s science has been discredited.

Fresh evidence also suggests that Nikki died from pneumonia leading to sepsis. She had suffered antibiotic-resistant infections, requiring treatment in hospital — where she was given toxic drugs now thought inappropriate for infants.

International law does not prohibit the death penalty, but allows it for only the “most serious” offences, defined as “intentional crimes with lethal or other extremely grave consequences”. Clearly, Roberson’s daughter died in his care, but there is no evidence that this was his intention, nor that a crime was committed.

For a conviction to be quashed by appeal courts, there does not have to be proof of innocence, only evidence that it is unsafe. In Roberson’s case, there is plenty. However, while exonerations of innocent people in America have induced some states to abolish the death penalty, US courts have repeatedly shown themselves reluctant to reverse convictions based on faulty science — as, until now, they have been with Roberson’s.

International law does prohibit the death penalty following unsafe and arbitrary processes, and insists that the evidence must be properly scrutinised throughout the trial and subsequent appeals. Yet despite the flaws in the prosecution case and the failure thus far to address them, Roberson found himself waiting hours from death while his lawyers and a bipartisan committee of politicians pleaded with the authorities to stop the execution.

Welcome as it was, his stay was far from timely, and his ordeal could arguably be seen as torture — which unlike the death penalty, is prohibited under international law.

This has led some abolitionists to consider whether the death penalty per se could be also defined as torture, and indeed, some of the 55 countries that retain capital punishment have already determined that long spells on death row in themselves constitute unacceptable mental anguish, often described by psychiatrists as “death row syndrome”.

In Jamaica, for example, any prisoner who has been on death row for more than five years will have their sentence commuted to life. In America, the average gap between sentencing and execution has climbed to about 23 years. Like other US death row inmates, Roberson will have spent his time on the row largely in solitary confinement, all the while aware he is likely to be put to death.

Arguably, this alone amounts to “cruel and unusual punishment” in breach of the US constitution, and a case could be made that, like his wait to learn if he would live or die on Thursday, it equates to torture.

Yet prisoners’ rights to appeal when the state intends to kill them cannot be curtailed, especially when science is evolving: there is, therefore, a contradiction between avoiding death row syndrome and allowing enough time for appeals. Abolishing the death penalty altogether is the only feasible way to resolve it, and to remedy its myriad injustices.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe