Children are supposed to be going back to school soon. In our borough, primary-age children are expected to return on 4 January; there is to be a staggered return for secondary schools, but they should all be back by the 11th. Reports suggest it won’t happen, and that Tier 4 areas are going to learn their schools are to be shut, but Michael Gove says he is still “confident” they will remain open.

But should it? Just before Christmas, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine released modelling, taking into account the new B.1.1.7 variant of Covid that has been spreading in the South-East and elsewhere. Their central finding was that Tier 4 restrictions as they stand will not bring down the R value to below 1 — and, in fact, that even a national lockdown like that in November would not do it, “unless primary schools, secondary schools, and universities are also closed”, until at least 31 January.

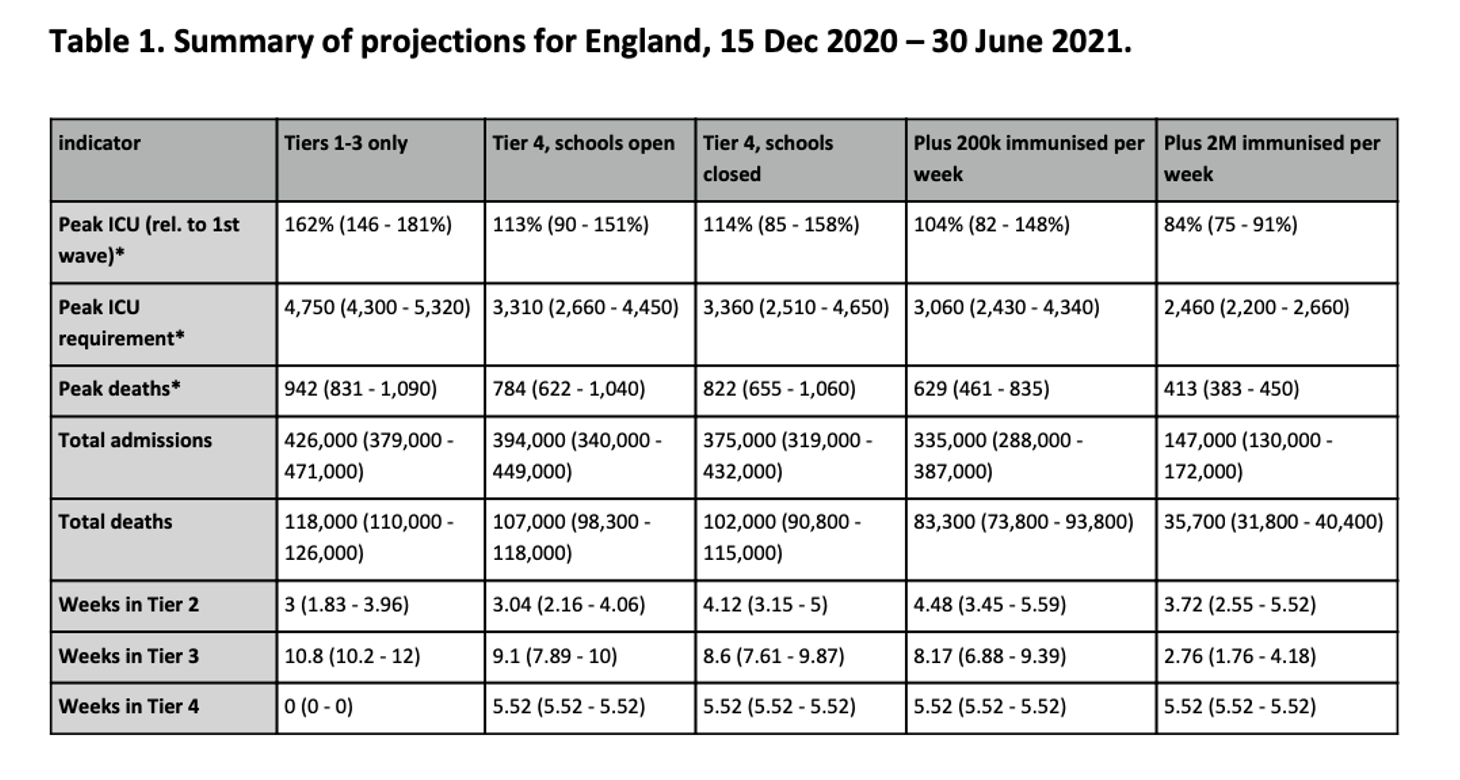

It’s worth going into a bit more detail, though. The total forecasted deaths between December and June, under a “Tier 4, schools and universities open” scenario, is 107,000 (95% confidence interval: 98,300 – 118,000); under “Tier 4, schools and universities closed”, it’s 102,000 (90,800 – 115,000), a difference of 5,000.

Let’s not belittle that. It looks like a small detail, because we’re so inured to awful news and because the numbers are so big already, but using those central estimates, we are talking about 5,000 lives, and probably more than 50,000 years of life, saved or lost. If it was 2,000 vs 7,000, we’d be much more concerned, but the actual number of lives saved would be the same. But it does suggest that schools are not one of the main drivers of transmission, if together with universities they cause less than 5% of the deaths.

I spoke briefly to Sarah Lewis, a professor of genetic epidemiology at Bristol, and Sunil Bhopal, a paediatric epidemiologist at Newcastle. Lewis felt that the estimates the model gave are very high — she points out that if we vaccinate 2 million a week, we’d have vaccinated the country’s 12 million over-65s by the middle of February, and since they account for 90% of the deaths it’s hard to see where 36,000 come from. And both pointed out that there are significant costs to keeping children out of school, in terms of learning loss, mental health risks, risks of exploitation and abuse. The children themselves are still at almost zero risk from the disease: the age-adjusted mortality data for the new variant, says Bhopal, looks much the same as for the old one.

Perhaps keeping children out of school until the end of January is not a disaster, for the price of saving 5,000 lives. But Bhopal makes the case that these tradeoffs need to be made explicit: what is our best estimate of the costs? How many years of schooling lost are worth a year of life saved? What will be our trigger points, in terms of cases per 100,000, for closing and reopening schools? What measures should we take to mitigate harms while schools are open? These questions need to be openly asked and answered.

What really makes a difference under this model, incidentally, is how quickly the vaccine is rolled out. The model adds either a 200,000-vaccinations-a-week scenario or a 2-million-vaccine-a-week scenario to its most stringent scenario above, and finds that under the 200k/week scenario, total deaths drop to a central estimate of 83,300 (73,800-93,800); under 2m/week, it’s 35,700. Schools, according to this modelling, have a non-negligible impact, but it’s vaccines, and how fast we can get them out to people, that will be the key difference.

Of course, it makes a difference to the calculations over whether to close schools, as well. The vaccine’s arrival means that we are no longer simply postponing Covid deaths but avoiding them; the costs of closing down are lower and the benefits are greater. It may well be that, given what we know and don’t know now, keeping schools closed until February is the right choice. But I would like to see the reasoning made explicit, and soon, because we’ve only got a few days before they go back, and parents need to plan. Hopefully this upcoming announcement will make things clear, because rumour and anonymous briefing is not the same as clear communication.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe