King Charles III ascends to the throne as a living paradox. He represents the apogee of the British establishment, yet he has spent over 70 years as a somewhat radical critic of modernity. He insists he is not anti-science, but is continually critical of its power over our way of thinking; he presides over a Christian nation but his philosophy finds its roots in pre-Christianity; part traditionalist fogey, part climate-conscious progressive, King Charles occupies a truly heterodox position.

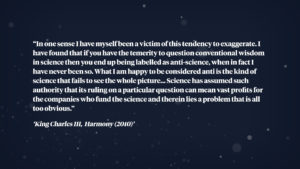

The central premise of his 2010 book Harmony is the disastrous consequence of humanity’s current relationship with natural world. We have come to view nature as a tool to exploit, something we rely on but are fundamentally separate from. By the King’s account, this stems from a philosophical breach that began even before the Enlightenment — we need to rediscover the wisdom of earlier ages.

The co-author of Harmony and long term friend of the King, Ian Skelly, explains to Freddie Sayers that King Charles is focused on “the complex systems that govern our lives.” “There is a reason we called the book Harmony” Skelly says, “if you extensively exploit these systems we rely on, then everything breaks down. The world joins up just as a piece of Back might do.”

The King’s philosophy, appears to be not just pre-Enlightenment but in lockstep with the pre-Socratics – a cohort of Ancient Greek thinkers preoccupied with concepts of unity, harmony, and togetherness. And these ideas find their expression down through early Christianity, they underpin Judaism and Islam, “the philosophies, if you like, of the primary peoples of the world who had not yet lost this sense of the sacred.”

It is visible, too, in Thomas Aquinas, who saw the natural world as an expression of divinity, “the animating principle at the heart of life.”

But by the 13th century there was a theological shift in Western Christianity, “which started to see God as separate from creation, something that was out there with a will and we were instruments of that will. That is a profound philosophical shift: we are left with a freedom that humanity sees as disconnected from creation. Everything became separate” says Skelly.

And now in the industrialised world we have become accustomed to viewing the world as a machine, a downstream harm of this psychological separation from nature. It seems in that process of modernisation – something King Charles is not opposed to, Skelly is keen to stress – we have lost a lot of wisdom and our discourse has become dominated by narrow scientific language.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe”He insists he is not anti-science, but is continually critical of its power over our way of thinking;”

The modern thinking is to Transhumanism, it is the 4th Industrial Revolution where people become one with computing by chip implants, or brainwave reading devices.

Yuval Noah Harari, the WEF’s main science guy is terrifying, have a look at what they see as the new human in just decades.

”“Now, fast forward to the early 21st century when we just don’t need the vast majority of the population,” he concluded, “because because the future is about developing more and more sophisticated technology, like artificial intelligence [and] bioengineering, Most people don’t contribute anything to that, except perhaps for their data, and whatever people are still doing which is useful, these technologies increasingly will make redundant and will make it possible to replace the people.””

”“The biggest question maybe in economics and politics in the coming decades will be what to do with all these useless people,” Harari said during a lecture. This particular lecture can be viewed on Rumble, though he has discussed this topic on multiple occasions. “The problem is more boredom, what to do with them and how will they find some sense of meaning in life when they are basically meaningless, worthless,” Harari continued. “My best guess at present is a combination of drugs and computer games.””

Thank God for Charles belief in Humanity and existence aligned with Classic Ethics and Morality. He is just the right man for the times.

”commeth the time commeth the man’‘ may well be true..

God save the King!

Very illuminating! Great interview.

King Charles shows evidence of paranoia. And his chosen “enemy” is science, or scientists. This is quite common with non-scientists. They do not understand science, and so they fear it. Of course science makes mistakes – 2 steps forward, 1 step back, same as all progress. And we can criticise science and capitalism and profit and industrialisation etc till the cows come home, but the fact is that life for most people is infinitely better for these things.

In a dense web of meaning and belonging, Death itself is no tragedy.

https://ukresponse.substack.com/p/the-funeral-of-queen-elizabeth-ii

Given his profoundly anti-mechanistic views of Humans and the Universe I would be excited by King Charles’ accession to the throne if it were not for his evident weakness of character and above all the snobbery and temper of which we have sadly seen glimpses this last week. If he fails as monarch, the ideas he embraces will suffer as well. And the Establishment would delight in blaming them for his failure.

”if it were not for his evident weakness of character and above all the snobbery and temper”

FFS

I think he is holding up remarkable well giving the situation. You are just worrying of Tabloid stories looking for issues to get clicks any way they can. – try thinking of the big picture.

And he is the opposite of weakness of character.

You can choose to avoid the evidence if you wish but shooting the messenger / blaming the tabloids does not alter the fact Charles had his whole life to prepare for this moment and acted with a stunning ego-centered lack of empathy for his Clarence House staff, who he fired, effete snobbery in waving away the pen stand from the desk, and petulant anger as he swears because he got ink on his hand. See links below along with an older one throwing his riding hat on the ground.

These incidents are some of many over the course of his life that sadly reveal a weakness of character that – along with his lack of intelligence (he came away with little more than a handful of O levels, although I think he may have obtained one A level) the very WEF crowd you reference has exploited. He has been allowed to speak his mind on issues such as our lost connection with Nature precisely because the Establishment does not take him – or that view – seriously.

https://twitter.com/divinemeghn/status/1569761942805397507?s=10&t=aASMC09dQZrHUdhteVoKEA

https://twitter.com/paulinemc2/status/1570097791753388033?s=10&t=TP1DXvvA7ePCg2bNPmW3eA

https://twitter.com/memerhelp/status/1569088404440190977?s=10&t=89xfQRJrmY9f5kbd62ztsg

You can choose to avoid the evidence if you wish but shooting the messenger / blaming the tabloids does not alter the fact Charles had his whole life to prepare for this moment and acted with a stunning ego-centered lack of empathy for his Clarence House staff, who he fired, effete snobbery in waving away the pen stand from the desk, and petulant anger as he swears because he got ink on his hand. See links along with an older one throwing his riding hat on the ground.

These reveal a weakness of character that – along with his lack of intelligence (he came away with little more than a handful of O levels, although I think he may have obtained one A level) the very WEF crowd you reference has exploited. He has been allowed to speak his mind on issues such as our lost connection with Nature precisely because The Establishment does not take him – or that view – seriously.

https://twitter.com/divinemeghn/status/1569761942805397507?s=10&t=aASMC09dQZrHUdhteVoKEA

https://twitter.com/paulinemc2/status/1570097791753388033?s=10&t=TP1DXvvA7ePCg2bNPmW3eA

https://twitter.com/memerhelp/status/1569088404440190977?s=10&t=89xfQRJrmY9f5kbd62ztsg

As a monarchist I agree with you but whats to be done.