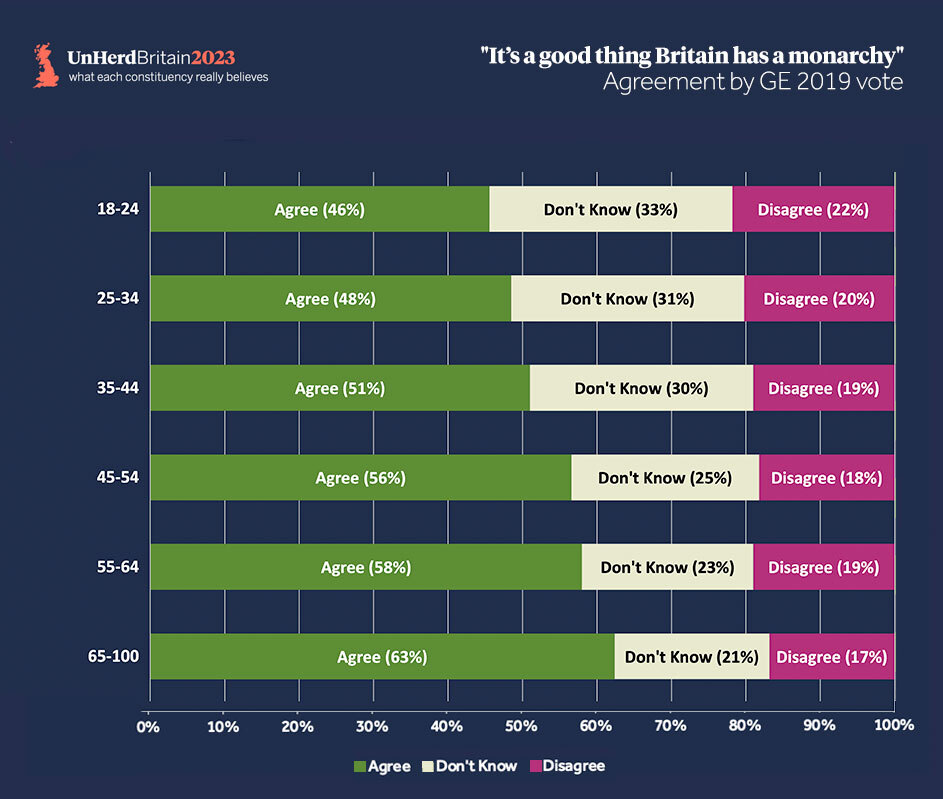

Almost half of young people believe that “it’s a good thing Britain has a monarchy”, the latest UnHerd Britain data has revealed. Of those between the ages of 18 and 24 who were surveyed, 19% were in strong agreement with the statement, and 27% in mild agreement. Of the remaining half, the majority expressed indifference, with only 10% strongly disagreeing. Coming from a generation whose loudest voices seem intent on damning all of Britain’s public institutions and what they represent, these statistics might come as something of a surprise.

Of course, compared to older generations, the 18-24s are still the least supportive of the monarchy overall. The data shows a steady increase in enthusiasm with each older generation: a quarter of 35-44s strongly agreed, a third of 55-64s, and so on. This is as expected, given that they grew up in a culture which unequivocally saw the monarchy as integral to British identity, with the feeling of national unity surrounding the late Queen’s Coronation still in living memory. The same cannot be said for Generation Z and millennials. And yet, among these demographics, those against the monarchy are in a minority. Why might this be?

One explanation emerges if we view this data alongside a major trend among young people: their increasing disillusionment with democratic politics. Among Gen-Xers and boomers, the biggest argument against the monarchy — or at least the one most repeated by republicans — is that it is “undemocratic”, which for them is necessarily a bad thing. For younger generations, however, such an attitude is no longer axiomatic. As a recent report by the think tank Onward found, today’s youth are more sceptical than ever towards democracy. They feel it is no longer fit for purpose, and have lost faith in its power to represent their values — or indeed, any values at all. Indeed, the report shows that 60% of the 18-24 group agree that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Parliament or elections” is a good way to run the country.

For many young people, modern democracy has come to feel like a spectacle, devoid of the significance it once had for their parents and grandparents. In a world dominated by the powers of international capitalism and technology, democracy’s ability to serve the interests of ordinary people seems ever more limited. Instead, politics itself seems now to be determined by “anonymous forces” whose intentions cannot be trusted, with many believing that corporations, the media and lobbyists have the most influence over policy. In other words, they feel that democracy has lost its “authenticity”, rendering it inherently suspect.

How might this affect their views on monarchy? Although many young people are likely to view the monarchy as suspect in other ways (for example, in its ties to colonialism), it might be plausible that royalty — in constituting an unchanging set of rites, symbols and values — appeals to them precisely because it sits above the chaos and confusion of modern politics, representing a form of authenticity that is otherwise non-existent in public life. In this context, the fact that Britain has an unelected head of state may even reassure them, for it guarantees that he is free from the perceived corruption of current elective processes.

In a similar vein, it may be that the pomp and splendour of the monarchy — however much it has been criticised by young people as unsympathetic to the cost of living crisis — provides a relief from the grey, uninspiring character of bureaucratic society. This is not just a matter of aesthetics: being imbued with sacral power, the monarchy is one of the last remnants of an enchanted world, which young people may come to yearn for in an age of secular materialism. It may be, then, that 46% of them agree that the monarchy is a good thing precisely because it is removed from the mores of modern life, and above the empty spectacle of politics.

Join the discussion

Join like minded readers that support our journalism by becoming a paid subscriber

To join the discussion in the comments, become a paid subscriber.

Join like minded readers that support our journalism, read unlimited articles and enjoy other subscriber-only benefits.

Subscribe“This is not just a matter of aesthetics: being imbued with sacral power, the monarchy is one of the last remnants of an enchanted world, which young people may come to yearn for in an age of secular materialism”.

At 40 years old, I am no longer young by any stretch of the imagination. Yet this is the strongest reason for me to still believe in the monarchy. When there’s war, the world order is shifting, the economy is hitting the skids, a robot has taken over my job and I don’t know where it’s all going…it is immensely comforting to look to these ancient rites and traditions that have endured through so many changes.

More than any other institution, it makes me feel like the present difficulties will at some point pass and that I won’t go under. It is a sort of faith that is not (directly) connected to the church.

“This is not just a matter of aesthetics: being imbued with sacral power, the monarchy is one of the last remnants of an enchanted world, which young people may come to yearn for in an age of secular materialism”.

At 40 years old, I am no longer young by any stretch of the imagination. Yet this is the strongest reason for me to still believe in the monarchy. When there’s war, the world order is shifting, the economy is hitting the skids, a robot has taken over my job and I don’t know where it’s all going…it is immensely comforting to look to these ancient rites and traditions that have endured through so many changes.

More than any other institution, it makes me feel like the present difficulties will at some point pass and that I won’t go under. It is a sort of faith that is not (directly) connected to the church.

The false assumption that underlies this article is that what we have now is a democracy. It isn’t. We are governed by a self-selected elite. Our Prime Minister has not been elected and does not carry out the policies put forward in a manifesto. Quite apart from that our system of local government has been entirely hollowed out, making the popular vote completely meaningless in that context as well. Despite having left the EU we still endure the consequences of decisions made by people we haven’t elected and can’t get rid of.

Next year we will elect a Labour Government on a manifesto that will be abandoned and replaced with an entirely different agenda as soon as their leader enters Downing Street. A compliant media will patiently explain to us why we can’t have the policies we voted for – just as it does now. There will be no consequences and no way to recall a government that will effectively have become a dictatorship as unaccountable as any in history.

Indeed. The problem is that the democratic process is leading to decidedly undemocratic results, so people are losing faith in the process, and looking for alternatives. Monarchy happens to be the most common type of government in recorded history, and maybe unrecorded history as well. Historically speaking, if the problem is a decadent aristocracy, (and what aristocracy isn’t), the cure is a powerful individual wielding autocratic power backed by tradition, popular will, religious practice, or any other force that can resist economic domination. Kings and Queens are human, true, but there’s a better chance of finding one person who can’t be bought, bullied, or manipulated and will carry out the people’s will than there is of finding several hundred. With monarchy, it’s a crap shoot based on the individual. Sure, you might get a Hitler, a Nicholas II, a Louis XVI, but you could end up with Elizabeth I, Frederick the Great, or Emperor Meiji. Given the state of the world and democratic governance, I can’t really blame people for assessing the situation and concluding that taking a spin at the roulette wheel of kings has better odds than participating in the democratic process. I personally have not voted since the 2008 bank bailout, and don’t plan to.

The Prime Minister is not directly elected in our Parliamentary system. A lot of truth about the weakness of local government, but many people aren’t that keen on stronger local government either. We have a different and much more centralised tradition than say Germany.

The issue has the biggest democratic disconnect is immigration. International treaties prevent effective control over immigration; the government doesn’t want to upset the Biden administration, and indeed may well be rather pro immigration overall in any case.

I don’t know what reason you have to think Starmer’s Labour Party will suddenly abandon their manifesto. I have no particular brief for them, but I doubt that will be the case. Blair’s government stuck to theirs.

Er, well, how account for the fall of so many recent governments if they are not in some respect accountable? Curious understanding of ‘history’.

Indeed. The problem is that the democratic process is leading to decidedly undemocratic results, so people are losing faith in the process, and looking for alternatives. Monarchy happens to be the most common type of government in recorded history, and maybe unrecorded history as well. Historically speaking, if the problem is a decadent aristocracy, (and what aristocracy isn’t), the cure is a powerful individual wielding autocratic power backed by tradition, popular will, religious practice, or any other force that can resist economic domination. Kings and Queens are human, true, but there’s a better chance of finding one person who can’t be bought, bullied, or manipulated and will carry out the people’s will than there is of finding several hundred. With monarchy, it’s a crap shoot based on the individual. Sure, you might get a Hitler, a Nicholas II, a Louis XVI, but you could end up with Elizabeth I, Frederick the Great, or Emperor Meiji. Given the state of the world and democratic governance, I can’t really blame people for assessing the situation and concluding that taking a spin at the roulette wheel of kings has better odds than participating in the democratic process. I personally have not voted since the 2008 bank bailout, and don’t plan to.

The Prime Minister is not directly elected in our Parliamentary system. A lot of truth about the weakness of local government, but many people aren’t that keen on stronger local government either. We have a different and much more centralised tradition than say Germany.

The issue has the biggest democratic disconnect is immigration. International treaties prevent effective control over immigration; the government doesn’t want to upset the Biden administration, and indeed may well be rather pro immigration overall in any case.

I don’t know what reason you have to think Starmer’s Labour Party will suddenly abandon their manifesto. I have no particular brief for them, but I doubt that will be the case. Blair’s government stuck to theirs.

Er, well, how account for the fall of so many recent governments if they are not in some respect accountable? Curious understanding of ‘history’.

The false assumption that underlies this article is that what we have now is a democracy. It isn’t. We are governed by a self-selected elite. Our Prime Minister has not been elected and does not carry out the policies put forward in a manifesto. Quite apart from that our system of local government has been entirely hollowed out, making the popular vote completely meaningless in that context as well. Despite having left the EU we still endure the consequences of decisions made by people we haven’t elected and can’t get rid of.

Next year we will elect a Labour Government on a manifesto that will be abandoned and replaced with an entirely different agenda as soon as their leader enters Downing Street. A compliant media will patiently explain to us why we can’t have the policies we voted for – just as it does now. There will be no consequences and no way to recall a government that will effectively have become a dictatorship as unaccountable as any in history.

‘being imbued with sacral power, the monarchy is one of the last remnants of an enchanted world, which young people may come to yearn for in an age of secular materialism.’

These are certainly my feelings as a Gen-Zer. I think this is particularly pronounced with the decline of Christianity and religion in general.

I’ve been quite relieved by this poll. I was worried my generation were outright rejecting anything that might be construed as sacred or transcendental or beautiful (and I say that as an atheist) – or, worse still, replacing it with the woke creed. Glad to see that might not be the case.

Do you mind me asking which year you were born in, Josh?

1997

1997

Thanks for that comment. We need more younger voices to contribute, especially those capable of thinking for themselves rather than following the crowd.

I think these comments are missing the opportunity to critique the use of “sacral” here. I don’t think whatever warm and fuzzy feelings people have for the monarchy bear much relationship to religious belief or observance. I appreciate your comments, but the idea that the decline of religion in public life might account for the durability of affection for the monarchy demands a lot of careful reasoning which is lacking in this article.

‘Sacral’ might give the wrong impression, but I think most people have a (potentially subconscious) desire to submit themselves to a higher authority ‘in the grand scheme of things’. With secularism we’ve seen that grand scheme shrink to things which are tangible but nonetheless abstract – the climate, social justice, the monarchy, etc.

Yes, we are but sheep in search of a shepherd. And yet, we do get to choose our master. Now, what are the criteria for the choice?

Yes, we are but sheep in search of a shepherd. And yet, we do get to choose our master. Now, what are the criteria for the choice?

‘Sacral’ might give the wrong impression, but I think most people have a (potentially subconscious) desire to submit themselves to a higher authority ‘in the grand scheme of things’. With secularism we’ve seen that grand scheme shrink to things which are tangible but nonetheless abstract – the climate, social justice, the monarchy, etc.

Along with others in this thread, I much appreciate your views, especially as coming from one of your age group. But I would very respectfully express my puzzlement over the belief of many people that atheism can produce, or serve as a basis for, a transcendental, sacred view of the universe. The wonderful Douglas Murray (whom I greatly admire) seems to be a leader in this philosophy. Big fan of God and his work; shame he doesn’t exist.

One really can’t expect to harvest fruit from an orchard planted with dead rocks. I’d respectfully ask you to consider the fact that our behavior and routines dictate our beliefs about as much as the other way ’round, and to re-consider the philosophy that has sustained and fueled the West for at least a millennia.

I’m in accordance with Murray. I have a lot of respect for Christianity, and I still see myself as a Catholic, culturally speaking, but at the end of the day I can’t believe in what I can’t believe in. Like all opinions, it’s not a matter of choice.

Actually, no one can believe in it. It’s totally unbelievable – “a stumbling block and foolishness” according to one famous believer. That’s why those who do believe, also believe that their belief was given to them rather than earned. And it’s why Kierkegaard’s Knight of Faith has to make a leap, to jump from what is safe and solid to what is frightening, risky, dangerous, unsure… from the reasonable to the ‘Ultimate Paradox.’ It is the very act of doing this unbelievable and impossible thing (the *right* unbelievable and impossible thing, to be sure) that changes your perspective, your heart, your life, maybe even your world.

Actually, no one can believe in it. It’s totally unbelievable – “a stumbling block and foolishness” according to one famous believer. That’s why those who do believe, also believe that their belief was given to them rather than earned. And it’s why Kierkegaard’s Knight of Faith has to make a leap, to jump from what is safe and solid to what is frightening, risky, dangerous, unsure… from the reasonable to the ‘Ultimate Paradox.’ It is the very act of doing this unbelievable and impossible thing (the *right* unbelievable and impossible thing, to be sure) that changes your perspective, your heart, your life, maybe even your world.

I’m in accordance with Murray. I have a lot of respect for Christianity, and I still see myself as a Catholic, culturally speaking, but at the end of the day I can’t believe in what I can’t believe in. Like all opinions, it’s not a matter of choice.

Do you mind me asking which year you were born in, Josh?

Thanks for that comment. We need more younger voices to contribute, especially those capable of thinking for themselves rather than following the crowd.

I think these comments are missing the opportunity to critique the use of “sacral” here. I don’t think whatever warm and fuzzy feelings people have for the monarchy bear much relationship to religious belief or observance. I appreciate your comments, but the idea that the decline of religion in public life might account for the durability of affection for the monarchy demands a lot of careful reasoning which is lacking in this article.

Along with others in this thread, I much appreciate your views, especially as coming from one of your age group. But I would very respectfully express my puzzlement over the belief of many people that atheism can produce, or serve as a basis for, a transcendental, sacred view of the universe. The wonderful Douglas Murray (whom I greatly admire) seems to be a leader in this philosophy. Big fan of God and his work; shame he doesn’t exist.

One really can’t expect to harvest fruit from an orchard planted with dead rocks. I’d respectfully ask you to consider the fact that our behavior and routines dictate our beliefs about as much as the other way ’round, and to re-consider the philosophy that has sustained and fueled the West for at least a millennia.

‘being imbued with sacral power, the monarchy is one of the last remnants of an enchanted world, which young people may come to yearn for in an age of secular materialism.’

These are certainly my feelings as a Gen-Zer. I think this is particularly pronounced with the decline of Christianity and religion in general.

I’ve been quite relieved by this poll. I was worried my generation were outright rejecting anything that might be construed as sacred or transcendental or beautiful (and I say that as an atheist) – or, worse still, replacing it with the woke creed. Glad to see that might not be the case.

Looking around the world, there are precious few examples that would make one wish for an elected head of state.

But there are even fewer which would make you want an unelected autocrat!

‘Democracy is the worst form of government… except for all the others’

‘Democracy is the worst form of government… except for all the others’

But there are even fewer which would make you want an unelected autocrat!

Looking around the world, there are precious few examples that would make one wish for an elected head of state.

I’d be interested to see the results of similar surveys held, say 10, 20, and 30 years ago. I suspect that it might be that as people get older they have more life experiences, and get broader perspectives on this and practically every other issue. In fact, I’d say as people get older they generally get wiser. And although teenagers might be very sure, and very loud, about everything, those opinions don’t necessarily hold up on the closer examination life experiences thrust on people.

I’d be interested to see the results of similar surveys held, say 10, 20, and 30 years ago. I suspect that it might be that as people get older they have more life experiences, and get broader perspectives on this and practically every other issue. In fact, I’d say as people get older they generally get wiser. And although teenagers might be very sure, and very loud, about everything, those opinions don’t necessarily hold up on the closer examination life experiences thrust on people.

If the church actually lived biblical values it might be more respected as well even if the public didn’t agree with everything. Justin Wokeby is the worst spiritual leader of CoE in its history even though Pope Francis is giving him a run for his money. Both soft men lacking fortitude and testosterone.

If the church actually lived biblical values it might be more respected as well even if the public didn’t agree with everything. Justin Wokeby is the worst spiritual leader of CoE in its history even though Pope Francis is giving him a run for his money. Both soft men lacking fortitude and testosterone.

“… Indeed, the report shows that 60% of the 18-24 group agree that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Parliament or elections” is a good way to run the country.”

If it was good enough for 1930’s Germany and the USSR (and several other places), it’s good enough for us unable to think for ourselves..

I’m assuming your comment is ironic. I certainly hope so. Of course both mass murderers might be more interesting characters than Mr Sumak…..

Yes.

Yes.

I’m assuming your comment is ironic. I certainly hope so. Of course both mass murderers might be more interesting characters than Mr Sumak…..

“… Indeed, the report shows that 60% of the 18-24 group agree that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Parliament or elections” is a good way to run the country.”

If it was good enough for 1930’s Germany and the USSR (and several other places), it’s good enough for us unable to think for ourselves..

I didn’t realise that it was a case of one or the other. Insofar as we have a problem with modern democracy, the fault does not lie with a constitutional monarch.

PS: What colonies?

Duego Garcia, though given the Americans demanded we boot all the locals out to give them a free air base arguably it’s more their fault as there’s no way they’d let us decolonise an island as useful as Guam (a U.S colony).

So it’s an American colony: American problem.

So it’s an American colony: American problem.

Duego Garcia, though given the Americans demanded we boot all the locals out to give them a free air base arguably it’s more their fault as there’s no way they’d let us decolonise an island as useful as Guam (a U.S colony).

I didn’t realise that it was a case of one or the other. Insofar as we have a problem with modern democracy, the fault does not lie with a constitutional monarch.

PS: What colonies?

Excellent article

Thanks

Excellent article

Thanks

Democracy within a constitutional monarchy would appear to be one of the more effective forms of government. We share it with Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Holland among others. It does require a strong sense of public service, civic pride and individual responsibility. Its imperfections are manifest, which is a good deal more desirable than totalitarianisms that insist all is as it should be. The greed for better tends to obscure appreciation of good fortune; only democracy allows for progress to the better.

Democracy within a constitutional monarchy would appear to be one of the more effective forms of government. We share it with Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Belgium and Holland among others. It does require a strong sense of public service, civic pride and individual responsibility. Its imperfections are manifest, which is a good deal more desirable than totalitarianisms that insist all is as it should be. The greed for better tends to obscure appreciation of good fortune; only democracy allows for progress to the better.

If Charles really did go for the gusto and seize executive power from Parliament I am sure a seizable portion of the public would support him.

If Charles really did go for the gusto and seize executive power from Parliament I am sure a seizable portion of the public would support him.

I really like the system in Naboo (Star Wars). I think it’s brilliant, the perfect mixture of Plato’s The Philosopher King, the youthfulness of the warrior and the ‘inspirational monarch’ found in high fantasy.

Good combination of hand, heart and head. Padme had a nice wardrobe, too.

Not again!

I was surprised by the results of the survey mentioned in the article that many people prefer living in a monarchy over a democracy. Personally, I value living in a democratic society where I have the freedom to express my opinions and ideas. That’s why I decided to use a moving service https://a-plus-moving.com/ to move to a country where I feel more comfortable and can enjoy a warmer climate.

I was surprised by the results of the survey mentioned in the article that many people prefer living in a monarchy over a democracy. Personally, I value living in a democratic society where I have the freedom to express my opinions and ideas. That’s why I decided to use a moving service https://a-plus-moving.com/ to move to a country where I feel more comfortable and can enjoy a warmer climate.

A sad and disappointing thesis, as are the comments in approbation. “We’re all poor sheep who’ve lost our way” as it goes in Handel’s The Messiah. Can it be that we are really just looking for daddy?

… the report shows that 60% of the 18-24 group agree that “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with Parliament or elections” is a good way to run the country.”

As one commentator says, “If it was good enough for 1930’s Germany and the USSR (and several other places), it’s good enough for us unable to think for ourselves”.

We know where this led, and it wasn’t the “sunny uplands”.

I wish. I fear it is more of a “life is too hard; keep me safe and tell me what do while I’m paid” attitude.

I wish. I fear it is more of a “life is too hard; keep me safe and tell me what do while I’m paid” attitude.

Sitting at Gatwick airport recently, and looking around at the people, I must confess to feel an aching for the repealing of the two Great Reform Acts of the late 19th Century: The very embodiment of Tocqueville’s comment that we are mistaking democracy for the will of the people, shuffled about in their appalling apparel and training shoes, swilling pints at 8 o’clock in the morning, glued to i fones and computers, not a book or newspaper in sight.

No, these are not our manual laborourers, and working class people of old from the mines, the shipyards and the steel works, whom I respect and miss…. these are the hoardes of Orwell and Kafka, the automatons who sit behind computer screens in offices, piling on admin costs and overheads to businesses, creating nothing, but ” do not reply” e mails, making every transaction ” on line” more complicated, wallowing in electronic bureaucracy, making every part of ones life more time consuming, avoiding decisions, evading their favourite word ” serrr…. lushuns”…..

Their ” anything to keep my job” unctuous, cowardly and sycophantic obedience to their Tory MP look alike line manager, is all that matters.

They already live in the work monarchy of a lower middle class totalitarian state, and are eroding any interest in, let alone understanding of ” demos” on a daily basis, and are the voter target of every political party.

“glued to i fones and computers, not a book or newspaper in sight“

You wrote this on a screen, and I read it on a screen, since UnHerd lives on screens.

Oh, the comforts of condescension. Feel free the join Ms Thornberry, you could lunch together, making sure, of course, that you use the correct forks and knives.

“glued to i fones and computers, not a book or newspaper in sight“

You wrote this on a screen, and I read it on a screen, since UnHerd lives on screens.

Oh, the comforts of condescension. Feel free the join Ms Thornberry, you could lunch together, making sure, of course, that you use the correct forks and knives.

Sitting at Gatwick airport recently, and looking around at the people, I must confess to feel an aching for the repealing of the two Great Reform Acts of the late 19th Century: The very embodiment of Tocqueville’s comment that we are mistaking democracy for the will of the people, shuffled about in their appalling apparel and training shoes, swilling pints at 8 o’clock in the morning, glued to i fones and computers, not a book or newspaper in sight.

No, these are not our manual laborourers, and working class people of old from the mines, the shipyards and the steel works, whom I respect and miss…. these are the hoardes of Orwell and Kafka, the automatons who sit behind computer screens in offices, piling on admin costs and overheads to businesses, creating nothing, but ” do not reply” e mails, making every transaction ” on line” more complicated, wallowing in electronic bureaucracy, making every part of ones life more time consuming, avoiding decisions, evading their favourite word ” serrr…. lushuns”…..

Their ” anything to keep my job” unctuous, cowardly and sycophantic obedience to their Tory MP look alike line manager, is all that matters.

They already live in the work monarchy of a lower middle class totalitarian state, and are eroding any interest in, let alone understanding of ” demos” on a daily basis, and are the voter target of every political party.